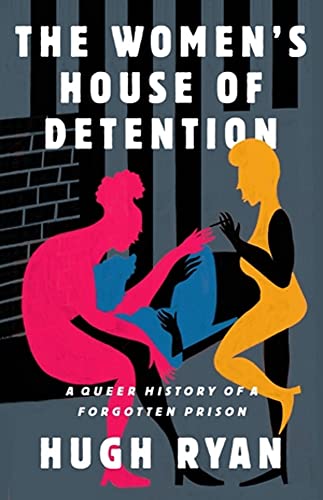

The Women's House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison

“a fascinating book written with style and passion and deserves the widest possible readership.”

The star of this enthralling book is the Women’s House of Detention itself, which occupied the space in Greenwich Village, New York, now taken by the Jefferson Market Garden, between 1929 and 1974 (1971 is also mentioned as a closure date). The “House of D” as it is named throughout was “one of the Village’s most famous landmarks; a meeting place for locals and a must-see site for adventurous tourists. And for tens of thousands of arrested women and transmasculine people from every corner of the city, the House of D was a nexus drawing the threads of their lives together in its dark and fearsome cells.”

Curiously enough for anyone only familiar with the current Village prisons in one form or another had dominated the area from as early as 1796 when Newgate prison (nicknamed for the famous London establishment) was established to receive prisoners “sent upriver” from the city.

During its lifetime the House of D became “a queer landmark” existing in strange symbiosis with the raffish, Bohemian, and rapidly gentrifying Village. Many detainees came from the quarter, and after release continued to hang out there, often sleeping rough in the parks while they visited friends and loved ones who were held awaiting trial, or were already tried and detained. “The House of D helped make Greenwich village queer, and the Village in return helped define queerness for America,” though the House’s noisy contribution to the Stonewall Uprising (1969) described in these pages is not often acknowledged elsewhere.

Hugh Ryan prefers to use the term “criminal legal system” rather than “criminal justice system,” considering the former more accurate in that prisons in general, including the House of D, often have very little to do with justice or rehabilitation but are used to hide and bury people considered by society to be problematic for a variety of reasons, which might include being homeless, wearing pants or otherwise “cross-dressing,” vagrancy, prostitution, drugs, lesbianism, not getting on with parents. . . .

“Most people in detention are there because they are poor, Black, female, queer, gender non-conforming, brown, mentally ill, chemically addicted, indigenous, abandoned by their families and the state, or some combination of the above.”

As Ryan shows the initial plans for the 11-story, Art Deco House of D reflected enlightened and reformist thinking with a state of the art hospital and plans for recreation and education, though it was not too long before early visions proved expensive and therefore unnecessary, and the House came to be known as “Alcatraz” or the “Hell-hole.”

On arrival, possible detainees were subject to an enema to find hidden narcotics (“none ever found”), and an invasive gynaecological exam often causing internal and external damage. Drug addicts could be confined for many days unattended in the “junkie tank.” The facility rapidly became grossly overcrowded and made very little attempt to provide educational or vocational skills for return to lay life. Early detainees were on release provided with a dime to launch them back into society. This largesse was gradually increased to 25 cents in 1957, and to $40 in 2021 which was the norm for the formerly incarcerated of NY City.

Ryan relies for his fascinating and detailed text on the voluminous and previously unused case notes of the Women’s Prison Association (WPA), as well as interviews with a few survivors of the House of D. The WPA was run by predominantly white and middle-class feminists, and provided much-needed psychiatric and medical care to inmates often for many years after their release.

The author interweaves detailed and often harrowing detainee biographies with skilful analysis of the social trends with which they found themselves in conflict; these trends include the changes in thinking on queerness, race, and Communism. He notes that many early detainees did not understand the “homosexuality” that they were accused of and had to look it up. And thinking on homosexuality also changed and was reflected in prisoner treatment. Perhaps homosexuality was not rooted in bodily differences, but something to be cured by psychiatrists?

In its heyday the prison was a haven for established butch-femme partnerships, and other ties intended to reproduce regular family relationships, though this social model was frowned upon by some later feminist detainees (including Andrea Dworkin arrested for protesting the Vietnam War) who preferred to define lesbianism against the patriarchy, and disapproved of what they saw as cosy, butch-femme reconstructions of “normal” life.

There are many detailed and fascinating case studies of detainees, including some famous Black queer women who were leaders in the Black Panther movement—Afeni Shakur, Joan Bird, and Angela Davies—whose political perspectives were fundamentally altered by the House experience, and whose later radical influence was fundamental in the eventual closure of the House of D, and to broader prison reform.

Some of the biographies have happy endings, though the many women experienced a lifetime of repeat detentions and lack of any prospect of salvation. Drug users in particular were “stuck in a negative feedback loop from hell.” The techniques of “finger printing piloted on sex-workers” made it almost impossible to escape their records and return to normal life. For many of these women “their only crime was in being women—the wrong kind of women: too masculine, too Black, too poor, too angry, too ill, too resistant, too strong, too vocal.”

A helpful addition to this complex text would have been some visualization of the timeline of events so key to Ryan’s analysis, showing for example the ways in which thinking on homosexuality was affected by World War II; the term’s inclusion in 1952 in the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM); the overlapping in the 1950s and early 1960s of Lavender & Red Scares. But these are details.

This is a fascinating book written with style and passion and deserves the widest possible readership.