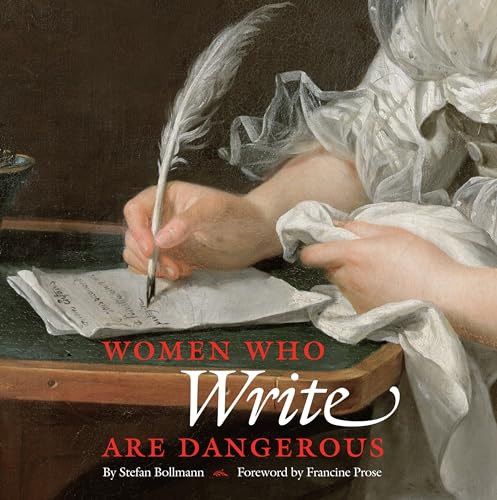

Women Who Write Are Dangerous

“Even within its self-imposed limitations this book could have done much more justice to its allegedly dangerous subject matter.”

Women Who Write Are Dangerous is a sequel to the bestselling Women Who Read Are Dangerous, and both part of the current flood-tide of publications excavating women from where they have allegedly been buried from public gaze. Many of the writers in this volume hardly need excavation (Jane Austen, The Brontes, Virginia Wolf, Beatrix Potter, Agatha Christie, Sylvia Plath, Margaret Attwood, Amy Tan, Elena Ferrante, Doris Lessing, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the list goes on). How did J. K. Rowling escape?

This book is promoted as the perfect gift for “any woman who writes” as “it reminds us that the ability to describe the world or to create another world, to tell the truth or to invent a higher truth worth telling, has after all everything to do with talent and intelligence, spirit and soul and nothing to do with our reproductive organs.” The target audience should then be not women who write but men and women who believe that they don’t or shouldn’t.

Traditionally of course a woman’s reproductive organs have helped to confine her to the home, and after the Preface comes a longish essay, presumably by Stefan Bollmann though it does not say so, which discusses how some celebrated writers—Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath—have managed to challenge and defeat “the ideal of womanhood.” The author notes that as male writers have female muses “it might be of crucial importance for the future of literature” if men were willing and able to assume this role for women.

Clearly this is not a publication that will find much favor with feminists, and indeed it is designed for the coffee table . . . a non-feminist one! Women authors who are controversial in terms of their views on sexual preference or gender identity—for example, Jeanette Winterson, Sarah Waters, Jan Morris to name a few—do not make an appearance , and only four out of “some fifty” of those present are non-white.

The commentaries on each author included are very slight. The piece on Virginia Woolf only mentions one of her novels, Jacob’s Room, which is not usually regarded as the most remarkable or innovative. And among the not-mentioned is Orlando inspired by her love for Vita-Sackville West. The page on Sylvia Plath does not mention any of her celebrated collections of poetry, and more than half of it is dedicated to one of her biographers—Ingeborg Bachmann—who may not be a household name.

Even within its self-imposed limitations this book could have done much more justice to its allegedly dangerous subject matter.