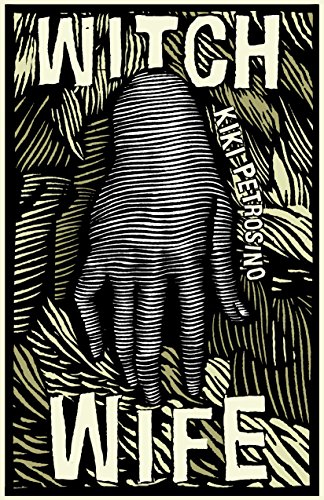

Witch Wife

Kiki Petrosino’s Witch Wife invites us to enter into a feminine, private world of post-puberty anxieties, love relationships, and nostalgia in which the desire for and fear of motherhood are ubiquitous.

In the collection of poems, we are taken along a rhythmic journey sowed with conduplicatos, diacopes, and expressive songs. The autobiographical collection mixes pagan, mythical, and pop-culture metaphors to show the mundane and banal as well as the most intimate.

Hard to place in a category or genre, the poems, which are all dedicatedly fashioned, range from strictly measured to free verse. While some poems convey passion and sense of refugee, some fall victim to stereotypical notions of womanhood or love failure.

The collection, made up of four parts, freely moves through several transitions or comings-of-age and switches with ease between the unwelcome bodily changes of “Whole 30” and the staccato, buzzing and vivid of “Twenty-One.”

Being a woman is an underlying thread in Witch Wife. At times, it seems Petrosino is fighting against the visceral idea that womanhood is defined by the ability to engender life.

“Three Little Gals” stages something in between bodily pressure and social pressure to give birth. In “Prophecy” she is told that she has “a good belly for twins” and that she should “rejoice in her blessings, you fool.” However, the ambiguity with which she picks this fight and the lack of an alternative notion leaves the reader thinking that Petrosino ends up believing that motherhood is the defining feature of a woman.

Another common thread in the poems is a nostalgia of failed, past relationships. There is an adolescent anxiety transcribed through the text as a fear that good things end up turning sour. A desire for a meaningful, corresponded relationship clings the poet’s soul. Petrosino expresses this nostalgia by asking insistent questions without answers, with memories and desires that come out in their own, strange, obstinate way (“Pastoral”: “We drank & I bled all the way home . . . You drink the drinks & bleed. You’re foam.”).

There are memories that are not cushioned in any particular context of desire, but rather in a very cerebral, foggy nostalgia, and that turn into humorous gestures or confessions (“Afterlife”: “My exes shall rise up from their Mazdas/& adorn themselves in denim.”). Petrosino originally incorporates these memories into her present by starting dialogues with characters from her past and ending those conversations in soliloquys.

One of Petrosino’s biggest successes in Witch Wife is the balance between the mundane and the mystical. In some poems it is the poet herself who is living with her body and negotiates its meanings in a serious, but always light-hearted or even purely descriptive way (“Thigh Gap”: “It’s true: I have it/though I hardly approve/of anything it does”) and tends to find peace within confusion and incongruousness (“Turns out, we agree/with everything we/do, almost.”).

At other times it seems we are wading through a ghostly, night time land of fairy tale visions, where words, images and their alliteration come to mean so much more than biographical referents themselves.

Witch Wife reads like a domain of suspended transitions, in which we pass freely from adolescent to 30-something to teenage experience. We go through a fan of experiences common in literature such as falling in love, loneliness, or desire and fear of motherhood.

Petrosino manages to use both everyday and storybook images to express these. However, even if very intimate, there is a distance in Petrosino’s work that can both fascinate or demotivate the reader: we never seem to trespass the notion of observer, of reader.

Perhaps the distance is because the poet, albeit in a lyrical and elegant way, decides to use a stereotypical map to navigate through what being a woman means.