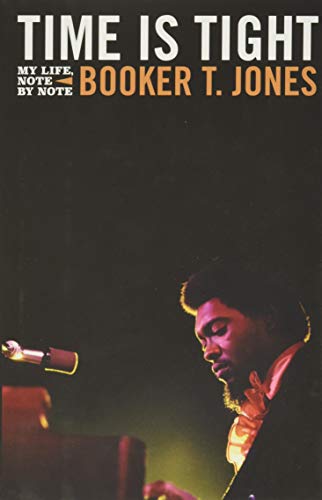

Time Is Tight: My Life, Note by Note

“Shattering epiphanies about old bandmates aside, Time Is Tight is, most emphatically, not a book about settling old scores. Jones chronicles his musical adventures and relationships with tremendous warmth, insight, energy, and clarity.”

As the house band at Memphis’ Stax Records, and the driving force behind the landmark recordings of Otis Redding and other luminaries of southern soul, Booker T. and the MGs’ impact on American music is almost impossible to overstate. So it should come as no surprise that Time Is Tight, the engrossing and often thrilling new autobiography of MGs bandleader Booker T. Jones, recounts one of the most momentous musical lives of the last 75 years without ever trading in overstatement.

Jones does, however, deal frankly and forthrightly with the significance of his story in the arc of rock and soul, as well as the MGs’ symbolic stature in the cultural landscape as a racially integrated band working in the 1960s in Memphis, which he calls “the most segregated of southern cities.”

“My band became the ‘face’ of racial harmony, literally and figuratively, from as far back as 1962,” Jones writes. “That has placed an inordinate amount of pressure on me to reassure the constituencies that it was indeed the case and confirm that the conception was accurate.”

Essential recent works such as Robert Gordon’s Respect Yourself (2013), Charles L. Hughes’s Country Soul (2015), and Jonathan Gould’s Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life (2017), have done much to debunk the feel-good story of Stax as a place that somehow locked out the segregation and white supremacy that surrounded it, creating a prejudice-free environment where egalitarian musical and social camaraderie reigned. These recent works have done much to correct and deepen the narrative, mostly by eschewing the tendency of previous authors to let white musicians alone tell the story.

Time Is Tight digs even deeper.

“You don’t have white and black working closely together every day in close collaboration without developing into some kind of family unit,” Jones writes. “That unit became an example of how the races could escape the plantation mentality, and with that also came a sense of comfort that failed to evolve into a sense of caring beyond the boundaries of our work space. As we were held up more and more as an example to the world of how integration could work, it became more and more of a veneer. I began to feel a responsibility for voicing the needs of my people and the struggle we were involved in. It came to where the social issues demanded us to identify our allegiances. I wanted my bandmates to champion civil rights, not just be willing to play with blacks.”

In one of Time Is Tight’s most powerful sections, Jones recalls the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 at Memphis’ Lorraine Motel, less than three miles from Stax.

Jones considers a quote from legendary white MGs guitarist Steve Cropper that he says he first read in Hughes’s book. Discussing King’s presence in Memphis in the weeks leading up to the assassination—helping to organize marches to support the city’s 1,300 striking black sanitation workers—Cropper blames the movement leader for stirring up trouble where he believed none had existed before: “I don’t think anywhere in the universe was as racially cool as Memphis was until Martin Luther King showed up.”

Jones recalls the anger, betrayal, and dismay he felt when he read Cropper’s words in Country Soul. “It hit me hard,” he writes. “This was the guitar player in my band speaking! How could I continue to knowingly collaborate with anyone who supported the mindset that made Dr. King’s murder possible?”

Jones discusses other issues with Cropper and the whites who ran Stax through much of its heyday, in particular the fact that Cropper was allowed to participate in—and profit from—the music publishing side of the business while Jones was not. Beginning with the MGs’ crossover smash “Green Onions” in 1962, both men wrote or co-wrote some of the label’s biggest hits over the next several years, working with a handful of collaborators; of the two, only Cropper saw royalties.

Shattering epiphanies about old bandmates aside, Time Is Tight is, most emphatically, not a book about settling old scores. Jones chronicles his musical adventures and relationships with tremendous warmth, insight, energy, and clarity.

Even Cropper has his undeniable moments, particularly in Jones’ description of the night in 1962 that the MGs cut their classic instrumental “Plum Nellie”: “Then, like lightning, the last guitar trill exploded! A fleet, acrobatic, musical stunt you have to hear to believe . . . After the take, [MGs drummer] Al Jackson said he ‘plumb near fell over his d—k’ when Steve played that lick. Hence the title ‘Plum Nellie.’”

Such wonderful moments abound in Time Is Tight’s thoughtfully, and not always chronologically, sequenced mini-narratives—“moments joined more by truth than minutes,” as Jones explains.

Jones writes with seemingly effortless grace about the ways musical collaborations come about and cohere. One of the most memorable is his meticulously detailed recreation of the session that yielded Sam & Dave’s “When Something Is Wrong with My Baby,” three minutes of sheer transcendence for the “Double Dynamite” singing duo and the MGs.

Jones writes about time signatures, chord progressions, and the wonders and intricacies of his beloved Hammond B3 organ in a manner both accessible and instructive that befits an artist of his achievements and erudition.

Some of Time Is Tight’s especially enlightening episodes concern the four years Jones spent at Indiana University getting his music education degree. Just 17 when “Green Onions” hit in 1962, Jones did what many newly minted high school graduates but few suddenly ascendant rock ‘n’ roll stars do: He went to college.

From 1962–66, as Stax built its reputation as Soulsville USA, Jones adopted an exhausting regimen of commuting between Bloomington and Memphis not just to make MGs records, but also to write, arrange, and perform on the hits that made Otis Redding and other Stax artists into soul music legends. Meanwhile he pledged the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, played in the IU marching band, student-taught, married his first wife, and became a father to his first son, Booker T., Jr.

Jones’s Bloomington years have always formed a sort of lost history of Stax in accounts such as Gordon’s, which typically and appropriately mostly just report his absences in that period. Of his education at IU, Jones writes, “It would be difficult for someone who didn’t have musical training and education to appreciate the full value they afforded me . . . By virtue of my proficiency on, and knowledge of, the ranges and capabilities of brass, strings, and woodwind instruments, I became a regular arranger at Stax, to my benefit and others’.”

Of course, Jones’s most exciting adventures are musical, and the characters that emerge in his travels—always evocatively described—provide some of Time Is Tight’s most memorable moments. He recalls accompanying gospel music giant Mahalia Jackson in a Memphis parlor as a precocious 12 year old, “completely swept into the strong feeling Mahalia created with every phrase”; his teenage soul brotherhood with future Earth Wind & Fire founder Maurice White; and his life-changing first encounter with Otis Redding, whose “tempestuous inner self was full of apprehension, yearning, and love for everything he touched.”

Over his three-plus decades in California after leaving Stax, Jones recounts deep musical connections forged with Carlos Santana, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Patterson Hood, and Sharon Jones. Time Is Tight also explores Jones’s friendship and fruitful collaboration with Willie Nelson—whose multiplatinum Stardust album Jones produced—and Nelson’s gentle generosity to all those in his orbit.

Those later years also include poignantly rendered moments of heartbreak and pain, from his two failed marriages to the still-uninvestigated 1975 murder of Jones’ incomparable MGs bandmate, Al Jackson—a 40-year-old wound still fresh. “Another black male life determined insignificant, not worthy of public concern,” Jones writes. “But I, for one, will never let go of this.”

The real beating heart of this wonderfully perceptive, generous, and open-hearted memoir is found in two places: in Jones’s account of his deeply fulfilling third plunge into family life with his 34-year marriage to Nan Warhurst Jones, and of course in his lively and revealing descriptions of those earth-shaking early years at Stax.

Perhaps Jones’s description of the recording of Otis Redding’s “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song),” which Jones says “captured the true essence of Otis Redding,” captures the essence of Time Is Tight’s enormous appeal as well: “I mimicked his vocal on the piano, playing along with a dancing rhythm of thirds up high on the keyboard, practically dancing at the piano myself. The dichotomy in Otis’s music and what we were doing at Stax was never more apparent than on this session—playing sad music to make us happy. Everybody had a ball that day.”