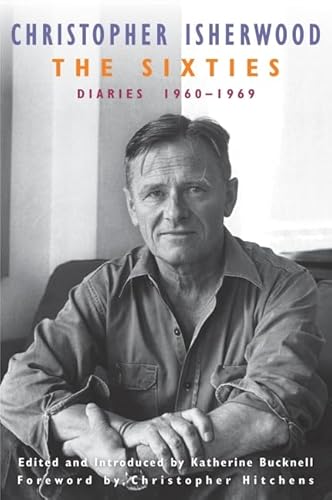

The Sixties: Diaries:1960-1969

There is something wonderful about a book that is unafraid of its footnotes. The latest edition of author Christopher Isherwood’s journals, The Sixties: Diaries 1960–1969, is rife with them and wears them as like a chest full of medals. As well it should, as they give the reader a reference point for the places and faces discussed on the page above.

Better yet, there is the thing that editor Katherine Bucknell—she who also created all those lovely footnotes—calls the “glossary,” which is to the usual glossary what Mar-A-Lago is to vacation houses. By all means, should you fall under the spell of these diaries, do not fail to dip into the glossary. It is where all the book’s research and the best of its gossip is hidden. Like an Easter egg in a video game. Like the lies that poet/critic/editor and sometime Isherwood friend Stephen Spender told: that he was a CIA agent chief among them. Or the true identity of the woman who was the basis for Isherwood’s most famous character, Cabaret’s Sally Bowles. But for that you must go fish.

Best of all are the diaries themselves. (This is the second of two volumes—the first, called Diaries Volume One: 1939–1960 was also edited by Bucknell and was published in 1997.) Would that every author of note kept such excellent records. It was Isherwood’s habit to buy a new notebook each August 26, the anniversary of his birth, and to begin again with the blank page, recording. As he puts it: “I shall try to write this diary like one of those French swine (Robbe-Grillet) who write a-literary novels, without psychology. I shall try to abstain from philosophizing and analysis, and stick to phenomena, things done and said, symptoms.”

At this goal, he fails gloriously. Despite his stated desire to stick to the details, he can’t quite help but use his talent for words when it comes to his diary entries.

Like this, his entry for June 7, 1961, in which he writes about a visit with his dear friend, poet Wystan Hugh (W. H.) Auden: “Wystan arrived this morning, and he and I went overt to [Stephen] Spender’s for lunch; he’s staying there. It was good to see him. I felt a great stimulation. Wystan always brings you into the very midst of his life—so near, indeed, that it is out of focus, so to speak. He mutters about everything that’s on his mind; feuds, unpaid bills, alternations to be made in proofs. Most of the time, you barely know what he’s talking about.”

There are many joys to be had in reading Isherwood’s private thoughts. There is the joy, for example, of witnessing the author’s own work as he wrestles with it: how he writes, rewrites, rethinks, and reshapes it. Not to mention how he judges the success of his own work.

Of his own novel-in-progress, Down There on a Visit, he writes, “But I feel confident that the whole thing does add up to something, and that it has an authenticity of direct experience and is altogether superior to the slickness and know-how and inner falsity of [Isherwood’s earlier novel] World in the Evening.”

The work of others falls under his judgment as well. Of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, he wrote that the novel was “one of the most truly beautiful novels or prose poems or whatever that I have ever read. It is prose written with absolute pitch, a perfect ear. You could perform it with instruments.”

Of his friend Jeremy Kingston’s working manuscript he writes, “At present it isn’t a novel at all, merely a huge pile of building materials.”

And, of an evening that he spent with dramatist Emlyn Williams and William’s wife Molly at a new musical theater piece called Elegy for Young Lovers, he writes, “Emlyn got a crick in the neck and drank most of the scotch out of a flask I had luckily brought with me. The set was the best part of the show; a 19th-century German Alpine engraving beautifully rendered, with spooky white Alps in the background and a carved wooden interior. As far as I was concerned, Han Henze’s music reminded me of pangs of arthritis, sudden and sharp and unpredictable.”

At the center of the narrative—and, make no mistake, these diaries have a superb narrative structure that puts many a modern novel to shame—is the story of Christopher Isherwood’s great love for artist Don Bachardy. By way of backstory, after seeing the young man on the beach, Isherwood met on Valentine’s Day 1953, when Bachardy was an 18-year-old college student and Isherwood, nearly 50, was an already-established novelist and British ex-patriot living in California. Despite the differences of their ages, the two quickly fell in love and remained together until Isherwood’s death in 1986. (Note that the excellent 2008 documentary, Chris and Don: A Love Story, is well worth viewing for those who wanting to know more.)

While the early days of their relationship was relegated to the earlier volume of diaries, the love story blossoms here. And Don Bachardy emerges as the most fully rounded and deeply felt of all of Isherwood’s characters, in that he was drawn from life. Throughout the 60s, the two part, reunite, argue and forgive, and, most important, endure.

When separated from Don in 1963, he writes: “Am starting to think a lot about Don, miss him, wish he’d write. But I won’t pester him. Why does he seem unique, irreplaceable? Because I’ve trained him to be, and myself to believe that he is? Yes, partly. But saying that proves nothing; the deed is done and the feelings I feel are genuine.”

Later, in 1967, he writes: “The day before yesterday I spent the whole day in bed, apparently as the result of eating some bad fish at Jack Allen’s restaurant. Being sick has become quite a strange experience for me in these last years and I find I don’t enjoy it any more. I am too old for it. Don was adorably sweet and kind and seemed to get real pleasure out of waiting on me, but I felt uneasy . . . Perhaps it’s just because sickness could now so easily be something terminal, and I don’t feel ready for that. . . . A terminal sickness means the breaking of your will and the thawing of your heart, and my will has never been tighter nor my heart harder. It is only in my relationship to Don that I can still feel vulnerable, anxious, pliable. Well, that’s a mercy at least. All the more so because, most of the time, he is so sweet and loving. His sweetness only makes me love him all the more—another mercy, certainly, that I’m not in the least afraid of being loved.”

Thus, these diaries are, in their core, a love story, set against a timeline roughly from the Berlin Crisis to the moon landing. While the world changes around them, Isherwood and Bachardy find constancy in each other. And, thanks to the deft record of these diaries, we bear witness to it all—and are all the richer for it.