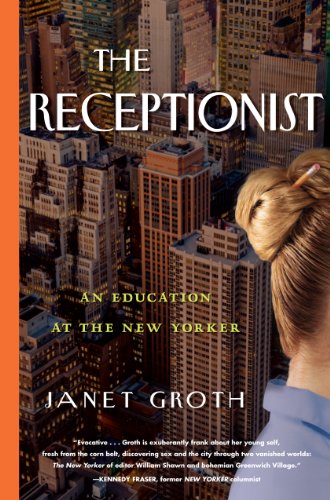

The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker

“Janet Groth is a one-woman cocktail party . . . [a] superb memoir.”

Literary Fallacy: Memoirs require certain elements like insane mothers, suddenly insolvent and/or abandoning fathers or unstable circumstance during youth, leading the memoirist to be come a drug mule, a gang lord, a political candidate, and/or a beat poet. That all good (in other words, publishable and/or sellable) memoirs require action, suspense, betrayal, and retribution, much like spy novels.

Literary Reality: No other memoir on the market today has half the charm, wit, or verbal dexterity of The Receptionist by Janet Groth, who writes of nothing more than her years answering the phone and taking messages for the writing staff of The New Yorker.

Indeed, she needs nothing more than her talent.

The author chose to subtitle her book An Education at The New Yorker—an apt choice as her story bears out. An equally accurate alternative could have been taken from a question she asked herself in the context of her memoir: “Why I stayed at The New Yorker for twenty-one years and never wrote a word for it.”

Ms. Groth lovingly recreates the world of The New Yorker, a place she jointly credits (an either/or situation that remains shrouded in mystery) Rogers Whittaker and A. J. Liebling as having defined as “a haven for the congenitally unemployable.”

Given that, her 21 years behind the reception desk up on the 18th floor, implacable as a Thurber dog, seem quite an achievement, especially when she expounds upon her job description:

“When J. D. Salinger needed to find the office Coke machine (there wasn’t one), I was the girl he asked. When Woody Allen got off the elevator on the wrong floor—about every other time—I was the girl who steered him up two floors where he needed to be. When Don Stewart was dating Jean Seberg and she needed to use the ladies’ room, I was the girl who unlocked it for her. When Maeve Brennan was homeless and sleeping on the couch in Jack Kahn’s office, she, too, found her way to the ladies’ room with a key from me. When Leonard Bernstein wanted to make sure his kid brother, Burt, knew he loved him, Lenny called me. When James Thurber needed emergency office space, I was the one who knew that Robert Coates was away and slipped him into Coates’s office so he could put one of this last pieces for the magazine—‘The Watchers of the Night’—to bed. When Delmore Schwartz was found dead in his hotel room, I was the one who located Dwight Macdonald to go over and pick up the pieces.”

Janet Groth introduces her cast of characters as deftly as a novelist. From the “overcoat clad, claustrophobic editor in chief” Wallace Shawn to the Pulitzer Prize winning poet (for his incandescent collection, 77 Dream Songs) John Berryman, whose suicide she movingly describes from his own point of view, imagining the things he himself saw in the moments before his fatal leap from a bridge:

“I imagined him briefly looking down at the river as a block of ice floated by, waving to a young couple kissing on the campus-side bank. Whether he performed either of those actions, he did jump a hundred feet to his death, a pocket of his overcoat yielding only one document, a blank check.”

Ms. Groth’s relationship with John Berryman was first as student and teacher and later as friend and colleague (although, she reports, when he was “between marriages,” he did propose to her more than once), and so she fittingly ends her memory of him with thoughts of him in the classroom:

“To see and hear Berryman lecture on a text he loved was to be in the presence of the transcendent. To describe it other wise would be imprecise—and he was ever one for precision.”

As is Ms. Groth.

It is the details that color her memories of her days at The New Yorker that give this book its rainbow hues. Like her description of Maeve Brennan:

“Hoping to add height to her tiny frame, [she] teased her hair into a five-inch beehive, which, in her bouts of lost perspective, turned into a terrifying tangle as she forgot to give it the occasional brush.”

Or the punch line to a memory built upon the time that Brendan Gill convinced her to throw a Christmas party for the staff of The New Yorker, something that editor Wallace Shawn finally forbade because he:

“Decided that we just can’t have that kind of office party here at The New Yorker. It would put the publication in too embarrassing a position if we were to be discovered throwing the very sort of office Christmas party the magazine has always satirized in its cartoons.”

Or the dandy, short remembrance of a great writer, critic, and wit:

“I noticed a buzzing cluster of people paying rapt attention to a tiny, watery-eyed woman dressing in black, sitting on a sofa with a gray poodle by her side. This could only be Dorothy Parker, of the wickedly funny bons mots. . . . I felt a shiver of excitement as I realized there was an empty seat on that very sofa, just on the poodle’s right. After standing on high heels for two hours, I overcame my shyness and took it.

“I remember mumbling something complimentary to Mrs. Parker (as everyone called her) and getting a bleary nod in return. Talk swirled around us, and Mrs. Parker’s head—rather small and tightly permed—dropped forward onto the white lace collar of her dark dress. I thought perhaps she was asleep. Somebody introduced the smudge-colored poodle to me as Cliché. The poodle remained impassive. Noting a box of dog biscuits open on the coffee table, I took one and, holding it out, asked, ‘Want a biscuit, Cliché?’

“Quick as a flash, Mrs. Parker’s head came up, her eyes now glittering icily through what seemed permanent tears. She barked in a voice I was sure was heard all over the room, ‘It’s not a biscuit, for Christ’s sake. It’s a bickie! Who d’you think you are, Henry James?’”

Even better is the lengthy chapter that stands as a tribute to author Muriel Spark, for whom Janet Groth worked (moonlighted, really) as an editorial assistant. She remembers:

“Muriel Spark was a tiny woman, and in the early days of our acquaintance, she possessed a headful of red-blond ringlets, a fluting voice, and the features of a porcelain shepherdess.”

In a chapter that could stand alone as a superb memoir, Spark is described fully, in gossipy-yet-loving detail, from her weight loss (“She had been . . . Brendan Gill delighted in telling around the office, ‘positively obese’”) to her tense relationship with her son, to the questions concerning her relationship and her sexuality:

“An Irish landlady of hers once observed, ‘You’re a bad picker,’ and Muriel could only respond, ‘How true!’”

In the realm of The Receptionist, each anecdote tops the one before, and Janet Groth is a one-woman cocktail party, chock full of tales and names dropped, along with wry whispers accompanying nudges to the ribs.

The reader is treated to not only the world of The New Yorker, a place with laughter ringing in the halls was punctuated by the ululation of the occasional suicide attempt, but also to a tour of Manhattan in an era in transition, when the lush nightlife (“We saw and heard Stan Getz and Anita O’Day. We caught Nina Simone at the Village Vanguard, Maynard Ferguson at Birdland, Roy Eldridge at Jimmy Ryan’s, and Bobby Hackett at Eddie Condon’s.) morphed into a new reality at the magazine:

“Through the violence that marked the years between Dallas and our final departure from Vietnam, the magazine and my protected spot at it began to feel less and less protected. There was theft on the editorial floors. Sam the shoeshine man was no longer able to get access and offer in situ shines. The sandwich cart from the lobby shop was barred. My desk was moved from its spot near the back staircase to a closed and windowed booth out by the elevators. All people with business on eighteen, and even those with offices there, had to be cleared and buzzed through locked doors by me.”

The story then, while a memory of a special time in a special place, is truly a tale of change, the same change from ignorance and innocence to jaundiced clear-sightedness that Janet Groth underwent as well. For The Receptionist is a personal memoir as well.

And we learn a great deal about Ms. Groth along the way:

“My female ideals were an incoherent mix of Lauren Bacall singing huskily and playing piano through cigarette smoke, Joan Leslie wearing puffed sleeves on the farm and Ingrid Bergman being impossibly brave.”

This aside, the image that remains of our author is one conjured by Ms. Groth’s therapist when, after their first consultation, he tells her, “I have a dream for you, Janet. I see us working productively together to get to the bottom of some of these problems that have been troubling you, until you walk out of here one day, a lovely woman, well at ease.”

In saying it, Ms. Groth tells us that he references Chaucer whose character Criseyde comments:

“I am mine own woman, well at ease.”

It seems today as if that were written to describe our author. The proof of it is on every page of this superb memoir.