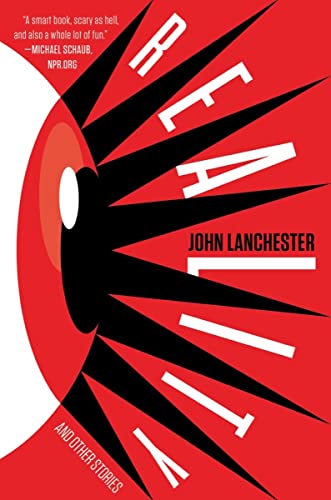

Reality and Other Stories

“‘Why am I here?’ he keeps asking, up until his inevitable execution at which point his keeper finally answers: No more questions.’

A noble atmosphere of ghost stories haunts this collection of eight tales by John Lanchester, Reality and Other Stories. But what “reality” do his characters encounter, and what does the author mean by it?

Nothing quotidian, be assured.

Lanchester does not deliver gratuitous melodrama. The horror he conveys is understated, put forth as a sinking feeling that each of his beset characters is lost and that familiar territory can never be recovered no matter how hearty the effort.

Screams do not emanate from these pages. Neither does hysteria ambush the reader, nor familiar tropes of the horror genre. Instead, Lanchester forces his characters—and by extension us—to confront a dawning realization that all is not well, that one’s hitherto framework of comfortable assumptions is about to collapse in spine–tingling ways.

The author’s atmosphere of disquiet captures the disconnection and distractions that stem from today’s relentless digital technology.

Some readers will find themselves, perhaps, in the uncanny world of The Twilight Zone or Black Mirror wherein common household tools have a mind of their own: phone calls from unknown numbers insistently harangue, and reality TV shows instill a creeping suspicion that none of what they depict is in any sense real.

Lanchester brings gothic sensibility to a set of modern stories that question the ways in which we grapple with technology, its assuring promise of convenience, and the unrelenting way that digital devices and the interruptions they inflict disconnect us from whatever meaning we extract from everyday life.

Some readers will know Lanchester from his two most popular novels, The Debt to Pleasure and Capital. In terms of psychodrama, in which feeling outweighs action, he channels the spirit of Henry James.

His humor can be arch at times. In the opening tale an unnamed protagonist, invited to spend a holiday week at his wealthy friend’s estate, notes that, “It was at that point that it became clear he had ascended the new stratosphere of international wealth.”

In other stories the humor is slyly understated:

“I thought he was gay.”

“So did I.”

“So did his boyfriend.”

Elsewhere otherwise unremarkable observations instill dread, such as massive portraits “of formally dressed people from previous centuries frowned from above the unlit fireplace.” Another hapless man, listening through headphone to simultaneous translations at an academic conference, hears a threatening narrative that is not merely wrong, but fatal. When he glimpses a figure at a distance “that only vaguely resembles a man . . . What I mainly feel, even at this distance, is unease, even fear.”

He ends up in what seems to be a Kafkaesque hospital in which he cannot bear the presence of any kind of paper with writing on it. What is this institution, he asks repeatedly to the silent attendants. Why is he effectively being incarcerated? “Why am I here?” he keeps asking, up until his inevitable execution at which point his jailer finally answers: “No more questions.”

Questions arise in these pages, as they should in all good books. Readers will smile at convoluted sentences such as, “He hugged like a natural non-toucher who had taken professional instruction in how to overcome his instincts and hug, and then found, greatly to his own surprise, that he liked it.” We learn that sans souci was once the palace where Voltaire stayed when visiting Frederick the Great. “Now it has become a stock reply to tourists saying merci.” We encounter rare words such as “otiose,” which sent this reviewer to the dictionary.

Metaphysics makes an appearance, too, with references to a brain in a vat and questions about simulacra and reality versus illusion. How does one know that others are real? “Maybe it’s the stupid people who aren’t real.”