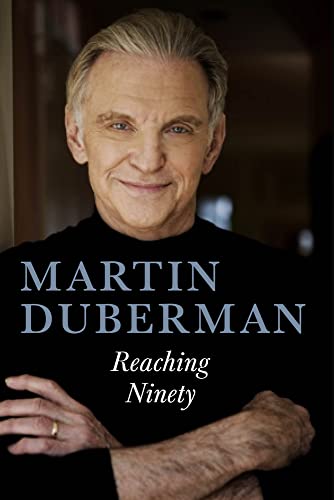

Reaching Ninety

“Despite his many travails and struggles, professional and personal—in relation to sexuality, class, ethnicity, and now ageism—Duberman acknowledges also his many successes in public as in private life.”

Reaching Ninety by Martin Duberman is a long, extremely detailed, but very rarely boring examination of and meditation upon his long life, as a white, gay, male; academic, writer, and playwright; political activist; and caring relative and friend.

Duberman describes himself as a second-generation Jewish boy from an immigrant family who “made good” and acquired confident possession of the “middle class basics,” which included his education at Yale and Harvard. He realizes with great regret toward the end of the book that he had never really known his father “a semiliterate Jewish farmworker” when he left Russia, and that his family life had been dominated by his glamorous mother, Flo, and her sister Tedda.

He describes his mother as typical of her generation of women, well analyzed in Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique (1963), as “boxed in to domestic routines” without the feminists’ vocabulary for self-analysis. After his father’s death she (triumphantly) opened “a tiny resale shop” feeling that she had finally “made it.”

At his private school Duberman was a successful student but also famous for his theatrical roles, often taking the female part no doubt helped by his “beautiful legs.”

His and his mother’s initial response to his harboring homosexual feelings was to enter “conversion therapy “ to which he submitted himself for many years only coming out in 1971, in his early 40s, after he had determination and courage to leave psychotherapy.

While much of his early writing pre-Stonewall (1969) contained implicit or explicit gay material he is clear that his actual coming out came at a career cost that affected critical and media acceptance of his work, and the kinds of speaking engagements, new book deals, and professional positions he was and is offered or refused. He remains convinced that his being dumped by the “heterosexual cognoscenti” was well worth it, and is unmoved though often disgusted by homophobic criticism of old and new work.

His earliest work focused on the Black civil rights movement (much later he completed a biography of Paul Robeson, at the invitation of Paul Robeson Jr, which attracted praise and controversy), and it was not until after Stonewall in 1969 that he became active in gay rights, and later specifically engaged during the AIDS crisis, campaigning for greater availability of effective drugs and working on AIDS hotlines.

One of his many professional struggles was to establish the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS) in 1991 at the City University of New York (CUNY) after an abortive attempt to establish the center at Yale, where he was a tenured professor. One of Duberman’s firm convictions is of the enormous value of a historical perspective in revealing the arbitrary and short-term nature of the hardiest of our favorite discriminations, and in casting doubt on the various blinkers assumed by current society relative to binarism, transgenderism, bisexuality, and other phenomena.

Duberman writes not only fluently, as one might expect, but with frankness and humor—and with profundity without pomposity.

Despite his many travails and struggles, professional and personal—in relation to sexuality, class, ethnicity, and now ageism—Duberman acknowledges also his many successes in public as in private life. CLAGS, the center that he was key in establishing, was twice awarded the Rockefeller Foundation’s Humanitarian Fellowship. He realized rather early on that his road to fulfilment was through his writing, and he has an impressive list of essays, books, and plays to his credit; perhaps most importantly he has found contentment with Eli, his partner of 35 years to whom the book is dedicated.