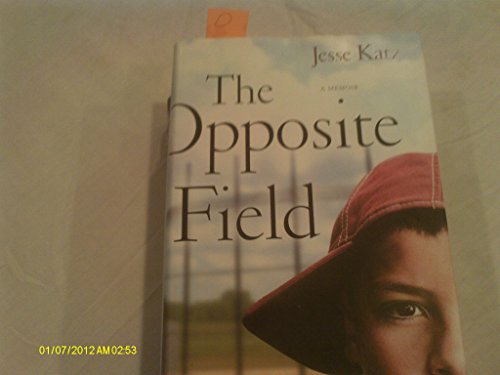

The Opposite Field: A Memoir

“Better bring your own redemption when you come/

To the barricades of Heaven where I’m from . . .”

—Jackson Browne

“Some nights I think, just maybe, I have found the place I belong.”

—Jesse Katz

There are probably just three groups of people who will be attracted to this memoir by Jesse Katz—parents, baseball fans, and those who love the greater city of Los Angeles. No, make it four groups, as nomads must be included. Nomads in this case being defined to include those who were born and grew up in one part of the United States but found their true, instinctual home in another part of the country.

Jesse Katz is one of those nomads but in his case it was genetic. His parents met and were married in Brooklyn, but felt the need to move a million miles west to Portland, Oregon. This was the pre-hip Portland, a city of mostly white persons before it became the ultra-cool city that attracted Californians—a city with a bookstore so big that it requires a map to find one’s way around inside it.

Author Katz grew up in a humble apartment complex near downtown Portland’s Chinatown, his father a suffering artist and later a professor at Portland State. Katz’ mother was a late bloomer, a Robert F. Kennedy inspired feminist-activist who eventually was elected to the State Legislature, then became the first woman selected as Speaker of the Assembly before becoming a two-term Mayor of the Rose City.

But this is Katz’ story which describes his escape from Portland as a teen, moving to the wilds of Los Angeles, a city that he so accurately describes as the anti-Portland. In L.A. Katz—“a white boy”—found that, “I had become a minority, the exception . . . I was a curiosity even. God how I loved it! Los Angeles . . . Where had you been my whole life?”

Katz first lives north of downtown before he moves to the multicultural community of Monterey Park. Monterey Park, a city of taco stands, noodle shops, and Mexican restaurants, bereft of national retailers, in which the local 7-Eleven sells the Chinese Daily News. There he burrows into the Hispanic-Asian suburb (yet an independent city) just seven miles east of downtown L.A.’s skyscrapers. And he finds a new life that centers around the seemingly minor sport of Little League baseball.

Katz, a reporter by profession, becomes the Little League coach of a team that plays at the La Loma fields in Monterey Park, coaching a team that includes his son Max. Max, unlike his father, is himself multicultural, the product of his Jewish father and Nicaraguan mother. The game of baseball as played by children may not seem to offer great lessons, but Katz comes to find the truth as expressed by writer John Tunis: “Courage is all baseball. And baseball is all life; that’s why it gets under your skin.”

The game gets under Katz’ skin to the point where he agrees to serve as the Commissioner of Baseball for the multi-age league centered at La Loma. This means that every waking moment for several years, not devoted to reporting on gangs for the Los Angeles Times or writing about the city for Los Angeles magazine, is reserved to keeping the league afloat. It is, in many respects, serious business but also fun . . . “I could not escape the feeling that Little League was like summer camp for adults, a reprieve from whatever drudgery or disorder was besetting our regular lives, a license to care about things, about events and people, that otherwise would have passed us by.”

Katz wisely chooses to omit little of the successes and failures that he encountered, both as “The Commish” and as the single father of a teenage son. This is a look back at a life lived both large and small, and a look at a city, Los Angeles, that embraces the people that make up its communities. Yes, the city and its suburbs embrace its citizens in a fashion that is far more real than the media’s myths of L.A.’s violence and tawdriness.

This reader, who lived in L.A. and learned to love it (and was embraced by it), would love to raise a toast to Jesse Katz (AKA Chuy Gato). Perhaps one day he will let me buy him a beer at the Venice Room in Monterey Park (“the seamy cocktail lounge that sooner or later everyone ended up at . . .”). A toast to greater L.A., the barricades of Heaven—a place to which we were not born, a place we discovered before it was too late.