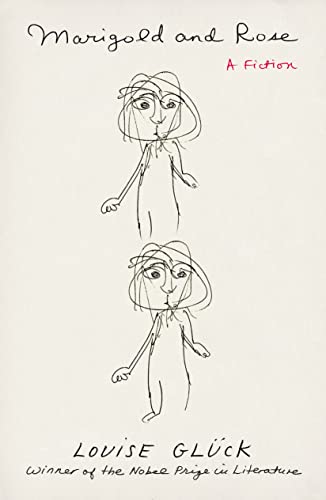

Marigold and Rose: A Fiction

“a gem of a book”

Not many books feature narrators who are too young to read, write, or even speak. Louise Glück gives us not one, but two, twin babies whose thoughts are the story in this small gem of a book. Glück has won many impressive awards, including the 2020 Nobel Prize in literature. In these pages, she presents two distinct personalities, each engaging the world around them differently, each learning about the world in a distinctive way. Marigold is the shy, bookish one. Rose the social, charming one:

“Marigold was writing a book. That she couldn’t read was an impediment. Nevertheless, the book was forming in her head. The words would come later. The book had people in it, but it also had animals. All books, Marigold felt, should have animals; people were not enough.

Marigold knew this was all utterly alien to her sister, just as Rose’s eager sociability and curiosity, her calm self-confidence, were alien to Marigold herself. This must be why they were twins. Together they included everything.”

The paragraphs switch perspective fluidly between the two sisters, but always the point of view is essentially that of a baby. Any parent will tell you that children’s personalities are surprisingly clear early on. That strong sense of an early self is brilliantly portrayed here. Different aspects of a baby’s life are described, including the parents and grandparents, but not in a childishly crude way. Marigold and Rose are excellent guides to their family, to their world. Their language may be sophisticated but that’s only to better convey their thoughts. For example, Marigold may not know the word “impediment,” but she certainly knows how things can get in the way of achieving one’s goals.

The book ends with the twins’ first birthday. Rose, who isn’t the thoughtful writer, recognizes that this kind of cheerful celebration is a fitting last chapter:

“It was night. For Rose, it had been a memorable day. Still, she was sad that Marigold had liked so little about the party. But parties, she believed had a special importance to people like Marigold who had important projects in mind. You could have a party in your book, she told her sister. It would be a way to get more people in, so more things could happen. It would even, she thought to herself, make a nice ending. End on a bright note, she thought, as though that were a good or even a possible thing.”

Glück brings the evocative spareness of poetry to paragraphs like these. The whole book, slight as it is, has the crystalline feel of a small jewel, pages precious in imagery and meaning. All of it is made more memorable by the ingenious use of the twin babies as narrators. It’s a tricky proposition but one that Glück pulls off brilliantly.