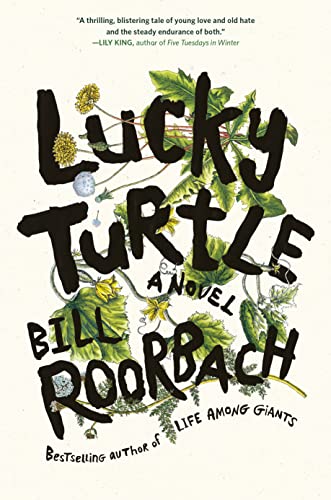

Lucky Turtle

“It is a love letter to all that is wild in the world, a rejection of prejudice and hatred, a suggestion that goodness can be imagined and made real.”

The leisurely, luxurious 19th century novel is alive and well in the first half of the 21st century, and it’s in the capable hands of Bill Roorbach, author of the bestselling Life Among the Giants and The Remedy for Love, as well as a wealth of well-regarded nonfiction.

Roorbach’s new novel, Lucky Turtle, spans a few decades, dozens of characters, and more plot twists than a reader might expect from Dickens or Thackery. Although at times the plot twists take on a melodramatic hue that might feel too colorful for these ironic times, Roorbach’s voice and vision are compelling enough to win the hearts of all but the most cynical readers.

The title Lucky Turtle refers to the main character, apparently a Native American but actually the scion of Thomas Sing, whose heritage is Chinese not Crow. Lucky contains multitudes. He is an innocent genius, a wilderness savant, a gentle spirit, a man of unshakeable courage and optimism. And, as in any fractured fairy tale (and Roorbach’s novel is surely a heartbreaking and heartwarming fairy tale for grownups), the hero finds a way to navigate the beauties and terrors of the world.

The narrative, told from the point of view of 16-year-old Cindra Zoeller (yes, sounds like Cinderella), starts in the late 1990s when Cindra is sent to a reform camp in Montana after a run-in with the law in Connecticut. If Lucky seems as mysterious as Heathcliff, Cindra is as likeable as Oliver Twist. When the two eye each other at Camp Challenge, it doesn’t take long for love to blossom. Sex, and a lot of it, follows. Then the terrors begin—a manipulative camp director with the Dickensian name Dora Dryden Conover; Dale Drinkins and the Montana militia; Walter, a hellish therapist and deceitful partner; an unsympathetic court system; and a generally unappreciative middle-class world.

One of the central characters in the story is Montana itself, as much a sentient presence as New Mexico is in Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. When Cindra is mistreated at Camp Challenge, she runs off with Lucky to a cabin in the mountains, and their idyll comes in glorious, unpretentious prose from her point of view. The story she tells is poignant and persuasive. Until they are joined by two other runaways: Franciella, from Camp Challenge, and Aarto, a Swedish special forces expert; they survive on lust, love, and Lucky’s wilderness skills. The story of the natural world—and what Cindra learns in it and from Lucky Turtle—is at the heart of the matter.

Roorbach manages both the woman’s narrative point of view and Lucky’s funny, startling, and laconic idiom with such skill that both fall like poetry on the page. Plot turns that might come off as preposterous from a writer with a smaller heart, work beautifully from Roorbach in Lucky Turtle. There is no internet, television, or radio in their mountain retreat, but there is a copy of James Michener’s Hawaii, and by the end of the story, the reader ends up appreciating the bestselling author as much as the narrator does.

Lucky Turtle winds its lovingly circuitous way from east to west and back again. It follows its characters through more than 20 years and a number of states, into prison and out, from naturalism to magical realism, from the sordid to the romantic. It is a love letter to all that is wild in the world, a rejection of prejudice and hatred, a suggestion that goodness can be imagined and made real. Luck, it intimates, might be a matter of seeing the good fortune that waits in the shadows.