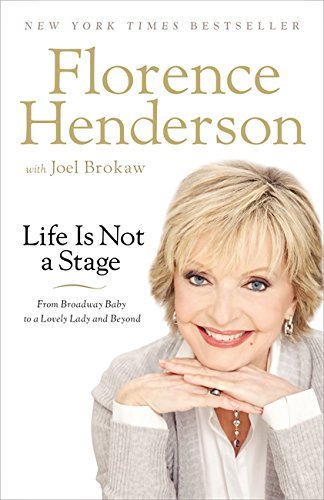

Life Is Not a Stage: From Broadway Baby to a Lovely Lady and Beyond

“ . . . [an] unflaggingly overbearing and underwritten memoir . . . At once Florence Henderson tells the reader far too much and far too little . . .”

“The spirit of rebellion, upheaval, and liberation was in full flower in the mid-to-late 1960s. With the Kennedy assassination, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights movement stirring the pot, the middle part of the decade was a molten-hot caldron that frequently boiled over to challenge all our assumptions as a society and as individuals. In Florence Henderson-land, that was quite the understatement.”

So begins a chapter of Florence Henderson’s unflaggingly overbearing and underwritten memoir, Life Is Not a Stage: From Broadway Baby to a Lovely Lady and Beyond. This chapter is called “The Pill,” and in it Ms. Henderson takes pains to explain the impact that the birth control pill had on Western culture and on Florence Henderson, not necessarily in that order.

(Florence Henderson, it seems, was able to obtain a doctor’s note that allowed her to take her birth control and still remain a devout Catholic. And yet, the onset of birth control was seemingly the beginning of the end for her first marriage.)

More important than birth control, the Vietnam War, and chaos in the streets is a simple place that Florence Henderson here lets drop (and not for the first time), one that defines the locale for our story—whether it is geographically set in the Southern Indiana of her childhood, or in New York City or Los Angeles—and, indeed, of any story that involves Florence Henderson. That place is known only as Florence Henderson-land, and, from what this reader has been told, it is a very, very, very nice place, if a bit blurry around the edges.

You see, no matter the facts of the anecdote, each story contained with in Life Is Not a Stage is set in the Technicolor land that exists only inside Florence Henderson’s head. Thus, when JFK is killed in Dallas, the question that rings out is whether or not that evening’s performance of The Girl Who Came to Supper must go on. (In the end, Florence Henderson visits a church to pray, the show goes on, but closes the next night and for a few nights thereafter.)

Stranger still is this, from Chapter One, “The Faith of a Child:”

“’Please, can I go home?’

“When I got the new of my father’s death, I asked for a leave to travel back to Indiana. His funeral was to take place in two days. I had just been cast in the lead in the national touring company of Oklahoma! We were set to open the next night in New Haven. It was the big break, a dream come true for an eighteen-year-old girl. It had come only months after I had moved to New York City to study theater and hopefully to find work.

“At the first opportunity during the rehearsal, I had gone over to Jerry White and Richard Rogers. The director and the composer were seated in the audience of the empty theater in New York. ‘We don’t have an understudy for you yet, and the place is sold out,’ Mr. Rogers told me in sympathetic but no uncertain terms. . . .

“Ironically, I knew that this dilemma, as gut-wrenching as it was at that moment, was within the natural flow of an improbably, sometimes horrific, and often miraculous young life. Despite the abandonment, neglect, and poverty I experienced as a child, I had an abiding faith I would do better than just survive. I knew with an absolute certainty that everything we going to be okay at the end. I felt the undeniable presence of a guiding and protective hand from a higher power above. This gave me a sense of optimism, as if my spirit was still free in spite of my circumstances.”

And so, what is the conclusion to this story, surely the most ghoulish ever to open a theatrical memoir?

“Form many reasons, it would have been impossible to tell Mr. Rodgers that my family came first and they would have to get along without me. Mr. Rodgers’s ‘the show must go on’ mentality was not to be violated.

“Naturally, I felt tremendous guilt about the situation. But secretly, deep down inside, there was a sad truth. I was relieved that I didn’t have to go to the funeral.”

And so, in the end, the show went on, with Florence Henderson in the lead.

And the show has been going on ever since, meaning that things are going pretty much as they should in Florence Henderson-land. In a memoir whose covers can barely contain the raging ambition that has been stuffed behind the mulleted-hair and the wide, toothy smile, Florence Henderson makes one thing clear: This place here all around us—should all the maps suddenly tell the simple truth—this place is Florence Henderson-land pure and simple, and those not wishing to comply with its rules (smiling countenance, upbeat attitude, perky good looks) had better start building an ark.

As Ms. Henderson herself writes:

“I had decided at a very young age that performing was what I wanted to do. To make that happen, more was required than just natural talent. To go beyond singing in church or in the shower, a performer needs an endless supply of grit, determination, and a passion for performing. If I was having a bad day or things were just not going my way, these qualities helped keep my priorities in focus and made me more tenacious in my commitment.”

Endless supply, indeed.

Perhaps because her birth mother abandoned the family while she was still a young girl, Florence Henderson seems to have had the uncanny ability to become her own stage mother. As if channeling Rose Hovick, Florence Henderson gets herself to New York, into theater school, onto Broadway with a small part that gets her noticed, and ultimately grabs the lead of the national tour company of Oklahoma! It is during this tour the she makes that fateful decision that the show must go on, leaving the rest of her siblings to bury their father without her—a decision that she will make, to one degree or another, again and again, as she leaves husband and children, siblings, her sick and, finally, dead father— all in order to tap into her “endless supply of grit, determination, and a passion for performing.”

What amazes the reader is how little information is given along the way. In a memoir that throws crumbs of details—her one-night affair with New York Mayor John Lyndsay and her resultant case of crabs being one of the few reportable events—Ms. Henderson manages to star in a show written by Noel Coward and to spend weeks with The Master, only to come away with no anecdotes to tell, except of her own fatigue, and of the fact that, “during my long absence, Robert had suddenly transformed from an infant to a chubby-cheeked little baby.”

Is it possible that Noel Coward had not one clever thing to say during the rehearsals and try-out tour of The Girl Who Came to Supper? Or is it more likely that no witticisms penetrated Florence Henderson-land?

Worse, when we finally get out to Hollywood and Florence Henderson is cast in a new show called “The Brady Bunch,” and we settle in for a good chapter or two of stories from behind the camera, Ms. Henderson instead writes:

“Many people think those few years on ‘The Brady Bunch’ are basically the sum total of my career. In reality, the show as but a small part of my list of credits, but because of its lasting power, it is never going to go away. Such is the enormous power and penetration of the media. Many people would also assume that I could write several books on just ‘The Brady Bunch’ experience alone.

“Because so much has been written about the history and impact of the show already, I am not going to attempt that. In reality, it was not so chock full of dramatic stories as one might be lead to believe. We were a cast and crew that cared about each other like family, and we made sure to have a good measure of fun to balance the drama that live serves up. But it was hard work and long hours that were fairly routine day in and day out.”

Among the few, scant, precious details that we do get concerning “The Brady Bunch” are:

• That Gene Hackman had auditioned for the role of architect Mike Brady.

• That Robert Reed, the actor who beat Hackman out for the role, was “both a terrific actor and a very complex man.”

• That it was during the interrupted taping of her first bedroom scene with Reed that Florence Henderson took that director aside and said, “John, just back off. Don’t say anything or make a big deal about it, but Bob’s gay. He’s nervous about this scene.” And with that, Ms. Henderson, who sussed out Reed’s sexual issues all on her own, made things right with Reed, in that she “took special care with him to make him feel comfortable.” (She never says where his sexuality conflicted with her religious outlook or not.)

• That she never had an affair with television son Barry Williams, no matter what you think.

• That Ann B. Davis (Alice the maid) was a complete professional and close friend who taught Florence Henderson how to needlepoint during long camera setups.

• And that not even Florence Henderson thought much of Cousin Oliver.

So it is with the rest of the memoir. At once Florence Henderson tells the reader far too much and far too little: far too much in the sort of details (names of nannies and their particular skills and shortcomings) and far too little in the things she skips and dodges around while smiling all the way.

That, for instance, she married her hypnotherapist the second time around and went to live with him on a yacht is the stuff of sitcoms. But like the aforementioned “The Brady Bunch,” we are told very little about it, only enough for the reader to know that in Florence Henderson-land, it is the words that are not written that are oh, so interesting.