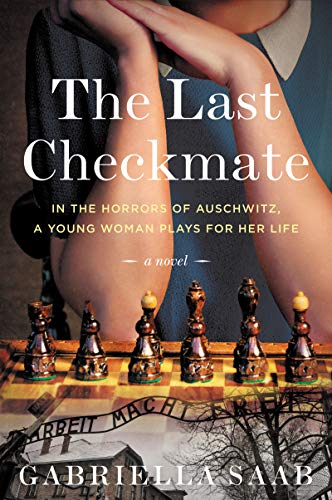

The Last Checkmate: A Novel

This novel has echoes of Queen’s Gambit, the Netflix series that reinvigorated chess for seemingly half the population. But whereas Queens Gambit concerned itself with fashion, sex ,and chess competition between genders, The Last Checkmate treads on much more serious ground, taking place as it does in Auschwitz during World War II.

Here we meet Maria Florkowska, a teenager from the Polish resistance, who gets caught and is punished by being sent to Auschwitz with her parents and siblings. Suddenly, what was once for Maria an abstract, almost fun, game of playing spy, becomes deadly serious. No sooner do they arrive in Auschwitz than Maria’s family is put to death, and Maria escapes only because a Nazi camp deputy by the name of Karl Fritzsch happens to notice a chess piece that Maria drops.

Fritzsch keeps Maria alive for his own amusement. What keeps her going is the search to find out how her family was killed and who killed them.

And so she plays Fritzsch in chess despite the uncomfortable surroundings: “Somehow, I feel like the girl surrounded by men in his roll-call square, all eyes on her while she engages in chess games against the man who would lodge a bullet in her skull just as soon as place her in checkmate.”

When she later suspects it was Fritzsch who killed her family, she vows to live long enough to get revenge. At first, she is one of the very few girls in Auschwitz but, as the war goes on, she is joined by others from her hometown and the girls and women form an underground network of support along with some men.

One of the novel’s central characters, the man who helps Maria realize her reason to continue living, is a Catholic priest who lives with a grace Maria cannot comprehend. He willingly gives up his food and ultimately gives up his life, trading places with a man who has children. It is largely due to his words, memory, and compassion that Maria decides she must keep putting one foot in front of the other.

As one might imagine, there are unimaginable horrors visited on the prisoners throughout the book which makes for some difficult reading. There are only so many torture-filled scenes that any reader can take, which is why the device of the underground network works so well. It provides some shred of humanity for the reader to hold onto.

The girls, women, and a few men sometimes ruminate on what life will be like when they are freed and return to their former lives in Warsaw. But for Maria, whose entire family has been wiped out, returning home without them is not something she looks forward to.

“A life beyond Auschwitz was what I’d imagined these past two years,” she thinks. “It was an encouraging thought, but, as I pictured myself back in Warsaw, I couldn’t erase my family from the image. We were together, as we’d been before. It was a wonderful dream, but that was all it was. Survival was easier to fight for when all it required was living from one day to the next; when it required a new life in a place once familiar and reassuring, now devoid of loved ones, of security, of vivacity, of home, it felt impossible.”

The chapters seesaw between the years 1942 and 1945 so we know that Maria does survive and lives to challenge her nemesis Fritzsch to one more game of chess. It is not the only game going on. There is psychological warfare between the two and, although Maria now seemingly has the upper hand, Fritzsch is still capable of pushing all her buttons.

The reader holds their breath as the tension rises, the games proceed, and the endgame begins.