Growgirl: How My Life After The Blair Witch Project Went to Pot

“. . . in constructing a book that is both a gentle polemic and a deeply felt, richly developed, personal memoir, Heather Donahue shows herself to be an author with talent, skill, and a uniquely rich author’s voice in which she can wrap them.”

In the beginning pages of her memoir Growgirl, author Heather Donahue writes, “I’m sure somewhere on the cover of this book will be the words The Blair Witch Project, and believe me, I will have tried to prevent that. There’s no me without it for any but the people I love. And even with them it takes a while.”

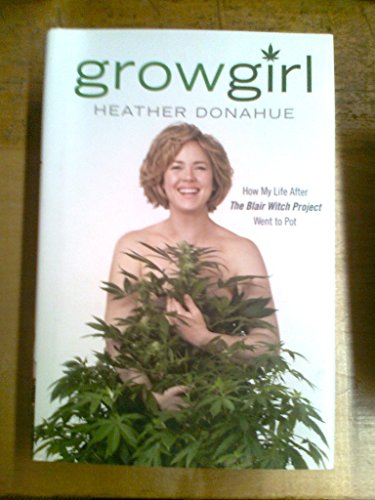

The reader then turns back to the cover and to that subtitle: How My Life After The Blair Witch Project Went to Pot and believes her. She, no doubt, fought against the reference to her single notable film—a classic of sorts—and to the whole mock-whimsy sound of it.

But then there is the cover itself, with a smiling Ms. Donahue clutching a marijuana plant to her seemingly nude form, suggesting perhaps a white void of a Garden of Eden into which our author, having left Hollywood behind (“It wasn’t until I did a movie called The Morgue and found myself sprawled on wet asphalt with apple juice dribbling from my mouth and rubber tubing suggestively across my face . . . that I had to think, Maybe this acting thing isn’t really working out.”) wholeheartedly leapt, a modern day Eve.

The problem with the package—that subtitle and the cover—is not just that they are not in any way artful or witty—they are not, but that is not the problem—but that they in no way represent the book that they are packaging.

All of which is sad to say, in that the publisher has given its author something to overcome in its presentation of the book, rather than something to build upon. In the pages of Growgirl, The Blair Witch Project—amazing success that is was, the first film ever marketed over the Internet—is barely mentioned, as it had nothing really to do with the book itself, except to say that the success of the film gave actress Heather Donahue just enough personal acclaim to allow her to hope that she could find repeat success in Hollywood, and, ultimately gave her something—that same Hollywood notion of success—to run away from when she moved to the Northern California town of Nuggettown, located somewhere in the greenery of Humboldt County or its environs, an area known both for its still rich veins of gold and for a somewhat newer new resource: marijuana.

And would that there were truly a place called “Nuggettown,” as it sounds as sleepy and happy a place as Mayberry. But Google Maps supports the notion that it is indeed a “nom de ville,” and a very good one at that—representative of the skilled and witty writing common to the book.

Because in the pages of Growgirl, Heather Donahue deftly manages three things:

First and foremost: She creates a whole world on the page, one populated by richly drawn characters. Based upon the real people with whom the author was acquainted or not during the single year that she spent growing medical marijuana, Ms. Donahue’s eye for detail and ear for dialogue places her at that top of the list of present memoirists and leaves her readers with a true sense of anticipation for the novel that she has stated is forthcoming.

Whether it’s the moment in the memoir in which Ms. Donahue, singing an original song in a local honkytonk while performing with a girl band comprised of her best friends, fellow grower Liz and waitress Willa, or the moment in which Zeus, the head of the hippie community of growers, gives Ms. Donahue her official grower name, “Madrona,” or the killer anecdote in which our author buys her parents (who have both come to know about and accept their daughter’s new source of income) a Christmas gift with a wad of cash, everything contained within this “Fish out of water” memoir rings true and reads fiercely and crazily entertainingly.

Consider that holiday moment with Mom and Dad:

“’What do you guys need?

“’We don’t need anything. We’re just happy that you’re safe.

“’What do you want then?

“’A flat screen,’ my dad says. ‘HD.’

“So my mom and I drive to Best Buy while my dad picks up the hoagie tray from Slack’s. Neither of us knows anything about TVs, but I don’t think it matters because they’re all so big and so clear that it’s really splitting hairs.

“’Do you want our product protection program? For a year it covers—‘

“’No.’

“’But you would have—‘

“’No.’

“’Cash or credit.’

“’Cash.’

“As I throw down a stack of Franklins (travel light!), my mom looks around the cavernous store like she’s just walked the dog without poop bags. We don’t get the biggest and most expensive, because blowing it up is how you call attention to yourself. I know that much, at least, though I’m not sure this knowledge means anything here. When I had the timing belt on the car replaced and paid with cash, the guy at the auto shop said, ‘What are you, some kind of drug dealer?’ And we laughed because obviously I was just a nice lady who—what? Doesn’t have a bank account? Sleeps on a mattress of twenties like it’s 1899 and she’s just off the boat from Palermo? I explained that I was conducting an experiment in onavorism, beyond organic, beyond local, to find out if a former city girl could live for a year on cash and seeds alone. Apparently, she cannot.

“’Oh, okay,’ he said, like it wiped his eyes of badness. Words are good like that.

“Not until you start paying with cash do you realize that nobody makes a purchase of more than five hundred dollars with it unless they’re part of an illicit economy. The cashier watches me count it out. Santa, I assume either makes his own shit or pays cash, like me. ‘I’m part of the Santa economy,’ I explain with no small amount of swagger.”

Swagger and cash payments are both part of Ms. Donahue’s second achievement.

While she literally risks arrest on Federal charges to do so, she manages to write an account of growing medical marijuana that is at once highly informative (this reader, for one, knew nothing of the intricate methods involved in growing “the girls,” as the plants are called, nor the intense labor and knowledge of cultivation it involves, nor, most important, the complex legal insanity surrounding the growth and distribution of the herb—for medical and non-medical uses—but came away from the book with a deeper understanding why those who seek legalization think as they do, even though legalization of marijuana would most likely very quickly lead to the end of their individual sources of income, as corporations very quickly would take over both farming and sales and distribution.

Obviously, Ms. Donahue is convinced of two things: that marijuana is indeed a medicinal herb that has much to offer many millions of Americans with chronic complaints and, and, second, that the government has no right to keep this herbal medicine out of the hands of those who need or want it.

Indeed, throughout Growgirl, she builds a strong case, morally, politically, and practically for the legalization of marijuana, and in doing so, makes this much more than just the amusing Egg and I variant that it seems on the surface. Should she wish to, Ms. Donahue could, by virtue of the cogent case she builds here, opt for yet another career change end up being an elected official whose ultimate triumph would be to give the nation the new freedom that she feels is both timely and just.

Finally, in constructing a book that is both a gentle polemic and a deeply felt, richly developed, personal memoir, Heather Donahue shows herself to be an author with talent, skill, and a uniquely rich author’s voice in which she can wrap them.

While the film industry did not seem to recognize her unique talent, let us hope that publishing industry is more discerning and, next time, instead of invoking the past glories involving that certain Witch, instead they allow Heather Donahue to be the very best and most interesting person she is capable of being—herself.