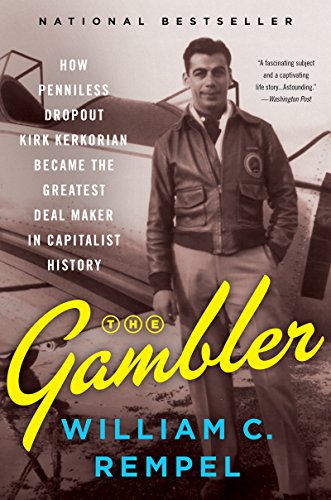

The Gambler: How Penniless Dropout Kirk Kerkorian Became the Greatest Deal Maker in Capitalist History

William C. Rempel faced significant challenges in writing a biography of Kirk Kerkorian, the obsessively private tycoon. Kerkorian died in 2015, leaving very few interviews and an inner circle of confidantes who honored his desire for privacy even in death. Rempel still managed to craft a detailed account of Kerkorian’s 98-year rags-to-riches story, especially his remarkable string of business deals spanning more than half a century, from the handful of his friends willing to talk and a few troves of documents.

Kirk, born Krekor, was the youngest son of Armenian immigrants living in California’s fertile San Joaquin Valley. His father thrived as a grape farmer for a time, but mounting debt forced the family of five to move to Los Angeles, where Kirk’s dad sold fruit on the street. Though shy and quiet, Kerkorian had an intense and thrill-seeking nature. He dropped out of school after eighth grade, worked odd jobs, and became a boxer like his older brother.

A chance introduction to flying in his early 20s led to a love affair with aviation and a dangerous job ferrying new bombers and fighter planes from Canada to Europe during World War II. After the war, Kerkorian started a charter plane company that grew with the new demand for air travel among civilians and the military. For many entrepreneurs, the story may have ended there: a pilot turns his passion for flying into a lucrative business. But for Kerkorian, it was just the beginning.

His need for adrenaline and proximity to Las Vegas made Kerkorian a regular at the casinos, where he frequently bet the limit. The hotel and casino business was in its infancy when Kirk began flying to Vegas, but he saw potential on a grand scale. With more capital and credit to his name after a couple of decades in the charter business, Kirk began buying parcels of land along what would become the strip.

A developer approached Kerkorian to lease his land for a new luxury hotel, a deal that gave Kirk lease payments and a cut of casino profits from the high-rise, eventually named Caesar’s Palace. Now a wealthy landlord, Kerkorian set his sights on the ailing Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, buying the movie studio and then systematically selling off its parts. His team was behind the famous auction of movie memorabilia, including Dorothy’s ruby slippers. Banking on that brand and nostalgia for the studio’s heyday, he built the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, at the time the largest hotel in the world.

As he moved from the airline industry to resort hotels, movie studios, car companies, and back to hotels, Kerkorian followed a pattern of identifying struggling companies with potential, then quietly and gradually purchasing enough stock to give himself a spot on the board, if not majority control. As his reputation grew, his acquisition of shares in a company would cause its stock price to skyrocket. On the occasions when his takeover bids failed, as in the case of Chrysler, his interest in the company had caused such a surge in the stock price that Kerkorian made a killing when he sold his shares in defeat.

Rempel describes some of Kerkorian’s quirks, like his fanatical punctuality and inscrutable poker face, but nothing too revealing. The few quotes directly from Kerkorian, taken from news articles or one documentary interview, are trite. He said to one interviewer: “Life is a big craps game. I’ve got to tell you, it’s all been fun.” That’s about as deep as Kerkorian was willing to go on the record, which is a shame. You can’t help but wish for more personal insights from a man of such great accomplishments and contradictions.

The close friends and associates of Kerkorian’s who stonewalled Rempel should not have worried about his reputation in Rempel’s hands. The author unearths not a single valid criticism of his subject and, through multiple anecdotes, shows Kerkorian to be a thoroughly honorable person, a good friend, and a fair dealer.

The only major missteps in Kerkorian’s seemingly charmed existence occurred in his romantic life. He was married four times, although one of those marriages occurred only on paper and lasted a month. Former tennis pro and charmer Lisa Bonder ruthlessly tried to take Kerkorian for everything he was worth. Lucky for him, his worth knew almost no bounds. He used to say, as only a billionaire could, “Anything that can be solved with money isn’t a problem.”

Kerkorian’s is an epic American success story worth telling, and Rempel assembles a dizzying amount of information about the deals that made him one of the richest men in America. Ultimately, in the words of his friend and contemporary Frank Sinatra, Kerkorian did it his way. He never wanted his name attached to his projects, and he despised public attention. Now in this most exhaustive biography, he remains as he was in life, a man of great wealth, power, honor, and mystery.