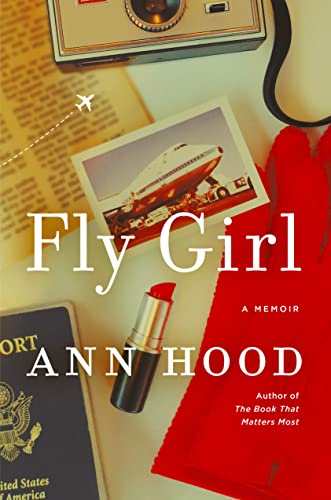

Fly Girl: A Memoir

If all you know about stewardesses (make that flight attendants) is based on the bestseller Coffee, Tea or Me, a salacious tell-all 1967 memoir by Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones, then you’re in for a shock: It was actually written by a man, Donald Bain. As such, it fulfills the male fantasy that flight attendants live an international round of La Dolce Vita that ends when they snare a man.

The airlines certainly encouraged that image. “I’m Cheryl, Fly Me,” said National Airlines. “Does your wife know you’re flying with us?” added Braniff, one of the worst offenders (the “air strip” was a Braniff original). And Pan Am opined, “How do you like your stewardesses?” A United Airlines ad from 1967 showed a pretty brunette with the legend, “Old Maid.” The blurb: “That’s what the other girls call her, because she’s been flying three years now. Everyone gets warmth, friendliness and extra care. And someone may get a wife.” The average time before attendants—who couldn’t be more than 32 years old, married, or be above a certain weight—quit to get hitched was 21 months back then, Hood writes.

Ann Hood’s highly readable Fly Girl is the real deal, a warts-and-all portrait of working the friendly skies for TWA (and a few other airlines) in the 1970s and ’80s. The overall impression is that there were plenty of sexist jerks, including some celebrities. One well-known author didn’t believe her when she said she’d written a book—because she didn’t seem smart enough. Maybe it was the uniform. The same idiot later showed up at one of her book signings.

Bad behavior in the air is recounted in great detail. One man went crazy when his choice of entrée—lasagna—wasn’t available. He ended up going berserk, having to be restrained and taken off the plane. A haughty Kennedy family member freaked out because her flight had no First Class, then demanded a Fresca, and refused to accept that the plane carried only Tab. A politician who told the public he always flew coach because he was a man of the people demanded she move him up to First Class. “The girls do it for me all the time,” he said. “Not this girl,” Hood said. Also turned down was a captain who wanted two Jack Daniels on the rocks.

Hood admits to mistakes. She spilled a Bloody Mary on a nun, who wasn’t mollified by the proffered dry-cleaning voucher. She dumped a salad on a businessman in 2C, and doesn’t stop there—we learn there were tomatoes, cucumbers, and croutons involved. On an early flight back to Boston from L.A. she was all ready to go to the airport at 6:00 a.m., but then discovered she hadn’t registered the time change—it was 3:00 a.m.

In between misadventures, we learn a lot about the mechanics of flying. The short hops, the long hauls, the layovers, the turnarounds. The worst was short flights around the Midwest; the best was overnight to Europe, with a weekend ahead. Attendants rented apartments in groups of six—because most of the time their roommates would be in the air.

The book can make you nostalgic for TWA in its glory days. Before deregulation, flying was expensive—New York to L.A. might cost $1,400, so it’s not surprising that First Class passengers got chateaubriand carved at their seats, with white linen and real silverware. Or that there were lounges that were like piano bars. JFK passengers took off from the striking TWA Flight Center, designed by Eero Saarinen.

Corporate raider Carl Icahn bought TWA in 1985 and gutted it, and that was the beginning of the end of Hood’s time in the air. TWA’s assets went to American Airlines in 2001, and the winged flight center deteriorated. But it’s now restored as the chic TWA Hotel.

Hood got laid off and worked for some budget airlines as fares plummeted and dinner service got skimpier. At the same time, the sexism was easing a bit, and flight attendants won some battles for better treatment. Men started getting hired, and strict age restrictions were abandoned. Another new book, The Great Stewardess Rebellion: How Women Launched a Workplace Revolution at 30,000 Feet by Nell McShane Wulfhart, is more political. According to Gloria Steinem, it tells the story of a group of flight attendants who “stood up to huge corporations and won, creating momentous change for all working women.”

Fly Girl is a lighter read, but it still provides a fair amount of period history and evolutionary change. The core of the book, though, is Hood’s own story. She loved the job, and loved how, in her words, all that travel turned her from a small-town Rhode Island girl to a sophisticated, cosmopolitan woman. She met some men, but it wasn’t the Mile High Club. And she found the time to write her first book, Somewhere Off the Coast of Maine (1987). Regrets? She has none.