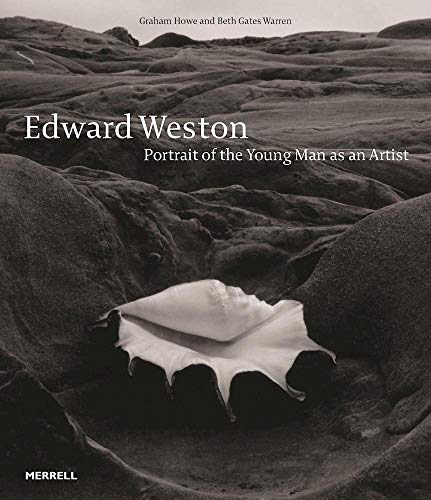

Edward Weston: Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist

“. . . thought provoking in its juxtaposing of images taken 20 years apart.”

Edward Weston: Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist by Howe and Warren, is thought provoking in its juxtaposing of images taken 20 years apart, and in revealing how the themes of youth become vastly refined and honed to the essentials in the hands of a master photographer.

The first section of the book ushers the reader into a visually intriguing interplay between the work of a young photographer and his latter self with a matured vision; it does this by placing images on facing pages of photographs taken by Weston in his early 20s contrasted with images he took in his mid 40s and 50s. The latter images are visual echoes of photographs taken many years before as fully developed themes. Seeing the growth of an artist firmly dedicated to his craft by this kind of comparison is fascinating and at times astounding.

Charis Wilson, writer, one-time Weston assistant, and lover whom he eventually marries wrote of him, “This kind of seeing—intuitive, intense and immediate—was the essence of Edward’s creative gift. . . . He may have honed his technical skills over the years, but ultimately, when we are confronted with his photographs, it is the Weston vision we respond to, it is the Weston eye that we are somehow seeing into as well as staring out of.”

What is typically seen, exhibited, and published of Weston are his later works that have benefitted from his development and overcoming the technical challenges of his medium. This book effectively pulls back the veil to reveal the origins, inclinations, and early fascination with certain subject matter, and how those intuitive impulses of the novice photographer would become powerful themes, and sources he would revisit again and again.

Beth Gates Warren writes a brief biography detailing the early circumstances in Edward Weston’s life. His mother died when he was five years old, and his sister, May, who was nine years older, took an active part in raising him. They became even closer when their father decided to remarry three years after the death of their mother. “The two Weston children took a vow to maintain a united front against the unwanted, stepmother, stepbrother, and step-grandmother who moved into their spacious home.”

His sister decided to marry while still a junior in high school, for reasons that the book does not disclose, and Edward spent a great deal of time on his own. When his father gave him a Kodak Bull's-Eye #2 roll-film box camera for his sixteenth birthday Edward gravitated to photography as something that engaged his passion, and focused all of his energies.

When May moved with her husband and three children from Chicago, Illinois, to Tropico, California, she strongly encouraged Edward to move there, too. After a brief education in photography he also decided to make a life in California.

Eventually what emerges in the biography is his fervent passion for photography, which despite a wife and four sons became the center of his world, and his reoccurring themes of nature and nudes which found the perfect environments in the California coast and desert.

The book’s brief text delineates Weston’s personal life, marriage, dalliances, and business ventures as an entrepreneur photographer. And although it lays out the chronological order of events regarding his first marriage and extramarital romances it does not draw inferences as to how those extramarital affairs and many romances were symptomatic of his thirst to broaden his creative horizons, or how they became fuel for his photographic fire.

Weston lived at a time when not only photography but also American culture was also moving away from the gauzy romanticism of the late 19th century to the increasing mechanization of the 20th.

By 1905 photography’s Pictorialism had given way to the Photo-Secessionists, and Stieglitz’s cutting-edge photo magazine, Camera Work. Weston evolved to embrace a photographic realism that was more accurate, bracing, and unsentimental, which reflected what he saw visually.

The book’s brief text spends a great deal of time on Weston’s childhood and experiences in California; however, other compelling aspects such as how his many lovers stimulated his creativity, what gave birth to his initial ideas on pre-visualization of the image; what drove his evaluation of tonalities to arrive at broader dynamic range (which possibly paved the way for Ansel Adams codifying the Zone System); or the content of his monumental meeting with Alfred Stieglitz in New York, are unmentioned or glossed over. Anyone seeking that kind of information might be better served by reading Weston’s Daybooks.

Edward Weston was key in the technical developments of modern photography by his influence on Ansel Adams and Minor White. Unfortunately, this book devotes minimal pages to Weston’s work methodology. The few things the book does mention is that while Weston was still in Chicago he purchased a 5 x 7-inch view camera; for studio work in California he acquired an 11 x 14-inch Graf Variable studio portrait camera; and in 1912 bought a 3 ¼ x 4 ¼-inch Graflex in order to capture expressions more quickly.

Edward Weston, Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist is a book with limited scope that offers the interesting but bare essentials of Weston’s development as an artist. Indeed, its most fascinating aspect is the juxtaposing of images taken decades apart. But with over 100 pages devoted to Weston’s classic photographic images, which are superbly reproduced on medium weight 10 x 11 inch paper, it is a large format book that will be cherished by everyone who appreciates the fine reproduction of Weston’s work and his integral place in the history of modern photography.