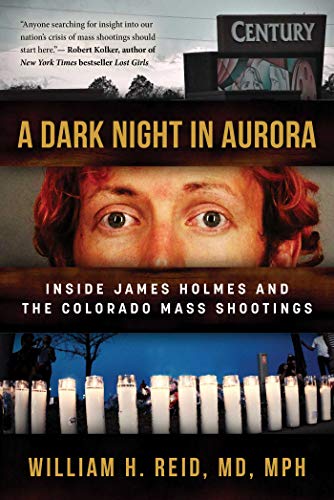

A Dark Night in Aurora: Inside James Holmes and the Colorado Mass Shootings

“a powerful book that delves deep into a seriously deranged mind.”

Let’s get this out of the way up front. When you hear of a mass shooting, are you riveted to your news source of choice, soaking up every detail, or are you so disgusted you can’t bear to hear another detail, not even the shooter’s name?

If you’re the latter, you can stop reading right now.

But if mass shootings fascinate you, if you long to understand why someone would carry out a detailed plan to kill as many people as possible, read on.

The author of this book, William Reid, is a respected and experienced forensic psychiatrist who was appointed by a Colorado judge to interview James Holmes, the young man who killed 12 innocent moviegoers taking in a midnight showing of the Batman epic The Dark Knight Rises back in July, 2012. Reid videotaped those interviews and was able to read his diaries and talk to his family.

If anyone has a fairly good idea of what James Holmes was up to that dark night in Aurora, it’s Reid. And he’s used his incredible access to deliver a powerful book that delves deep into a seriously deranged mind.

The story is frightening on many levels. Take Holmes’ early life with his family in Southern California. Nothing there that would raise an eyebrow. Holmes had a younger sister he doted on and grew up in an intact family of four. The worst anyone can say about them is that Holmes’ father was quiet. That’s not a crime. The reality was that all the family members cared for each other and Mom and Dad took the kinds of trips middle-class Americans take. There was nothing out of the ordinary. His grade school teachers testified that Holmes had a “wonderful smile” and was “a renaissance kid.”

So what happened?

To cut to the chase, Holmes had severe psychiatric problems that were hidden to everyone but him. He knew there was something wrong with his mind, but he could not stop it from destroying himself and others.

Even before he was a teenager, Holmes says his interior thoughts led him to think about killing people. Eventually he embraces the idea of “human capital” wherein he gains a point for every person he’s killed. He doesn’t feel the points lead to a longer life—he just thinks it would help his mental state to gain some “human capital.”

That is about the clearest answer possible for knowing why Holmes shot up that Colorado movie theater, killing 12 and injuring 70. And of course it doesn’t make any sense.

But it’s the story of how Holmes wound up in the theater that night that makes this true-life tale read like a thriller. We want someone to stop Holmes even though we know no one will. The author makes it painfully clear that many thought Holmes odd but almost no one thought he might be a killer.

He was odd but not a monster. Girls flirted with him. He dated and had sex with one. He fit in easily with a nerdy group in college and his peers thought well of him. He never displayed any type of anger and, although he played a lot of video games, he never played the games where the player has the point of view of a shooter.

In graduate school, he again blends in with a small group of neuroscience peers who seem to like his company. He lives off campus in a very ordinary apartment with a sad plant he nicknames Planty.

His search for a graduate school is interesting because although Holmes had the grades, he was lackluster in interviews and had that odd affect. Most schools rejected him after an in-person meeting with one professor going so far as to state that Holmes should not be accepted under any circumstances. It’s a measure of how perceptive some interviewers can be.

And then there are Holmes therapists who got to know him better than anyone. Holmes did seek out help for his social awkwardness and saw Dr. Lynn Fenton a handful of times. He told her about his fantasies of killing people but was cagey enough not to give her any details that would give her the ammunition to have him committed.

What Dr. Fenton did, with Holmes permission, was to have a colleague sit in for two sessions. She brought in Dr. Robert Feinstein. During the second session—about a month before Holmes shot up the movie theater patrons—he simply got up and walked out.

Dr. Fenton couldn’t sit by any longer, Reid writes: “She decided to override the usual conventions of doctor-patient confidentiality and activate something called the CU Denver BETA (threat assessment) team. The team was supposed to investigate and find a way to deal with any significant danger to others.”

The team investigated but found that Holmes had no criminal record and no weapon permits. It couldn’t know that Holmes had been buying guns and ammunition in a frenzy for months before the shooting. Around this time, Holmes dropped out of school and the team halted its investigation.

But Dr. Fenton went even further. She called Holmes’ mother who told the psychiatrist something haunting. She said, “I’ve worried about him pretty much every day of my life.”

Holmes parents were concerned. They were always present in his life and seemed to do as much as any parent can with a child who is having trouble adjusting to life. After Dr. Fenton’s phone call, Holmes’ parents called and offered their emotional and monetary support. Holmes used their money to buy his arsenal.

This is a tragic tale on many levels, not the least of it the way American laws have made it nearly impossible to imprison someone like Holmes unless they shoot up a movie theater and kill and injure scores of innocent victims.

Then the law gets involved when it’s way too late.