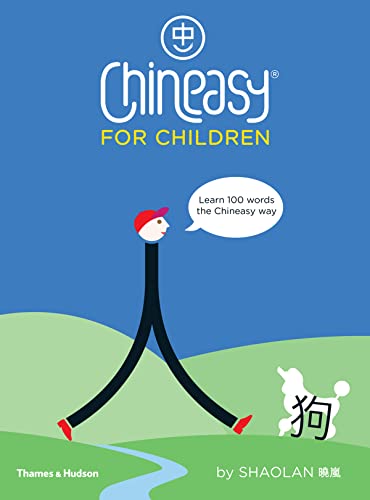

Chineasy for Children: Learn 100 Words

Learning a new language can be daunting, but Chineasy for Children makes it fun, if not exactly easy. The author, ShaoLan, does an excellent job of showing how Chinese characters derive from pictographs, making them more familiar to “read.”

She starts with the character for person, clearly drawn by illustrator Noma Bar in a clean graphic representation of an armless person striding. The next character looks like the trunk and branches of a tree and sure enough, that's the word for tree. Two together makes the character for woods and two trees with a third on top of them makes the character for forest. This kind of picture writing and reading is immediately accessible for kids and the way words are built will be fascinating to them.

This kind of making new characters is one way to make words, but ShaoLan makes a distinction between these composite characters and “phrases,” though it's not clear what the difference it. For example, when the character for big is put next to the character for person, it becomes a “phrase,” reading as big person or adult. Why the two trees next to each other created a new character rather than a phrase is a mystery. Another mystery is what is the character for little and if you put little next to person, is the new phrase “little person” or “child”? Unfortunately, the book doesn't include this information, one of the gaps that makes this inviting book less useful than it could be.

Another problem is that though the illustrator works hard to make the strokes of characters suggest the image of what they mean (from sun to mouth to clown to horse), the correlation doesn't always work. The author explains that the character for father looks like two crossed axes since long ago, men would chop wood to make fires for the family. That's a nice story, but the art uses the ax images to form a man's face (eyes, nose, and mustache), not axes, a kind of visual contradiction.

The art for mother is even more problematic. The character looks like a rectangle with a horizontal line through the middle and accent marks in each half. The illustrator has turned this into a woman's arm holding two babies (one for each half of the rectangle). Does this mean that only women who have twins are mothers? The character doesn't suggest the art here but is instead superimposed over. As a mnemonic device, it could work but seems a bit of a stretch.

Still, for all the images that don't quite connect, there are plenty that do. The book is clearly laid out, visually appealing, with simple explanations that are easy to follow.

Although the book is primarily an early guide for reading and writing Chinese, there is also a quick explanation of how Chinese is a tonal language and what those tones sound like. The author encourages parents, teachers, and kids to say the characters even if they get the tone wrong. It's more important, she stresses, to have fun. With this book, they'll be on their way to doing just that.