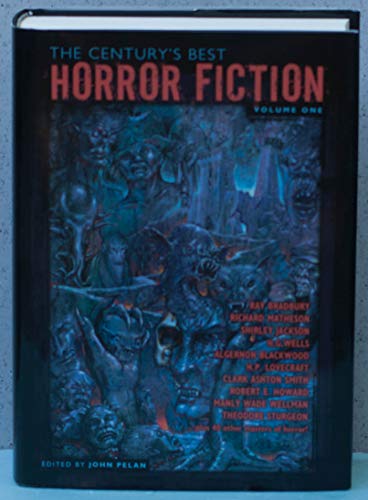

The Century's Best Horror Fiction Volume 1

“reading to get the chills is a perfectly acceptable use of this anthology . . .”

Editor John Pelan laid down two rules when he was working on The Century’s Best Horror Fiction 1901–1950 and its companion volume that rounds out the 20th century. The first was that the story had to be published in the year it represented. Sometimes he hedged this a bit with a story that was published a few years earlier in the 19th century but revised and republished in the 20th. That might be skirting the rules, but since he made them up in the first place, he certainly can interpret them as he wishes—as long as he applies it fairly across the collection.

The second rule was that on author could not be represented more than once. While that results in 100 authors’ work on display, it undermines the idea that these are the best of any given year. How can we be certain that another story by Shirley Jackson or H. Russell Wakefield didn’t have a superior story in another year but that they were simply prevented from appearing again by this restriction? Such a rule turns the “best” into more of a “top 100 authors” collection than a collection of the best of the best. Of course it can be pointed out that without clear guidelines to how stories were selected, this is merely one man’s opinion but at least in editor Pelan we have an expert making the selection.

This first volume hosts a range of horror tales but does not define what makes a narrative horror versus adventure or science fiction or fantasy or romance or any number of other genres into which literature is routinely sorted. Without such a definition, it sometimes felt confusing as to why one story was included over another that year in this massive book of 706 pages. What qualified one tale as horror versus science fiction or romance or adventure tale? While such a definition would have further limited the scope of the book, it also would have given readers a better understanding of Mr. Pelan’s mindset as he chose each piece. That would help with the next recurring issue in this volume.

Each story is introduced with a brief essay but what this essay contains varied from a comment about the author, the piece itself or how choosing it was either difficult or easy. Rarely, very rarely, does he comment on the social and political conditions that may have affected the nature, number, or quality of that year’s horror publications. Beyond rare comments on Mr. Pelan’s lingering memories of a particular story, we aren’t told why one story was picked and another rejected. We aren’t given much insight to what Mr. Pelan felt when he read and re-read the stories even when he does mention that they stayed with him for years. Are these ones that gave him nightmares or made him look over his shoulder for a few days? Are these pieces that influenced his own work or ones that he feels have influenced later horror authors? Are there any trends he noticed over the decades that might be explained by political, economic or social changes? Such analysis is very common in such collections and provides readers with greater context as they read.

The range of horror themes varied in this first volume, beginning with Barry Pain’s “The Undying Thing,” showing the costs of a sinful life visited upon subsequent generations of a family, told in a rather gothic fashion. Monsters were common themes during this era, and it isn’t surprising that we end the volume with Richard Matheson’s “Born of Man and Woman” with a viewpoint is both jarring and enlightening.

Ghosts turn up in several stories, including the particularly heart pounding “The Red Lodge” by H. Russell Wakefield and the very unique viewpoint characters of Violet Hunt’s “The Coach.” We also get introduced to paranormal investigators, serial killers, pacts with the devil, revenge, magic, freaky people, lost places, and so on and so forth. In all, there really isn’t a single theme that seems untouched in this volume, suggesting there is little new under the sun in the horror genre—though how the tales are told and the particular concerns of every decade or generation does seem to change.

Of the fifty names in this volume, only six belong to women. That isn’t surprising given that it has been the case until relatively recently that the “gentle sex” was dissuaded from writing for any audience beyond what a lady was supposed to read—or risk ruining her reputation not only as an author but as a lady herself. During this first half of the 20th century we should be both impressed by their accomplishments yet not tricked into thinking that these are the only women writing horror during this period. Let us never forget that some of the greatest gothic writers were women and the mother of the modern monster tale may be Mary Shelley. It has been the standard advice one can see in discussion among writers that women have to hide behind initials or false names to get published in some genres, yet only one of the women in this volume are “hiding” in such a fashion: C. L. Moore whose “Shableau” is the story representing 1933. We’ll have to wait and see if women fare better in representation in the second volume.

We should also reject the idea that only women can write powerful women characters. There are several male authors who write strong female leads, both protagonists and antagonists. R. Murray Gilchrist not only gives us the first vampire story in this volume, “The Lovers’ Ordeal,” but also a well-drawn female character who must rescue her beloved, reversing a common trend in literature of the damsel in distress.

Aleister Crowley’s “The Testament of Magdalen Blair” offers up a complex and believable character who takes us along for her journey of self destruction via a gift gone wrong. “Carousel” focuses on a young girl, and in her, August Derleth shows the power of childhood beliefs coupled with a realistic tale of domestic violence.

In the final analysis, this first volume of The Century’s Best Horror Fiction is more a mere collection of stories than a study of a half century of narratives to turn your blood cold and to haunt your sleep. It might be that this is enough for the average horror fan but for those of us who like to reflect on how our favorites genres change and develop over time, it leaves us with much work to do on our time if we so chose.

Lacking analysis of the entire half century or even consistence comments on each story, this book disappoints on several levels as a look back on a genre’s best. Of course, merely reading to get the chills is a perfectly acceptable use of this anthology as well.