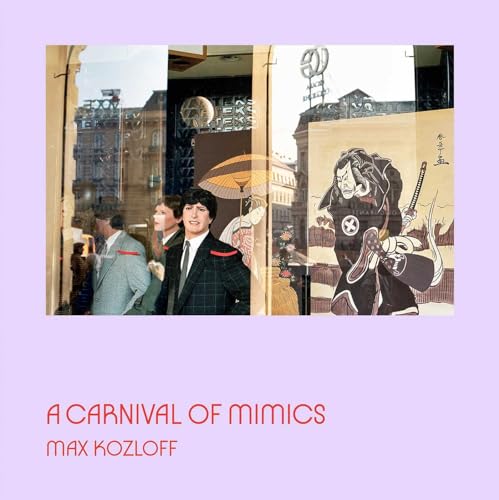

A Carnival of Mimics

In the beginning, the Bible tells us, God created man in his image. Depending on your point of view, we’ve spent the last four thousand or several million years trying to return the favor, creating him in ours. We’ve peppered our world with our depictions of ourselves, painting our bodies on cave walls and canvases, making sculptures to show how we’d be if stone, inking cartoons, and generating videos and writing long-winded dedications to our grandeur.

Some artists would tell you that this is all an effort to memorialize the human experience—our anger, our lust, our triumphs, our pratfall—to codify in creation that which we came by more honestly. The sculptor might tell you that she’d liberated from the marble the soul of a man, and the undertaker might tell you that he’s given life back to a husk.

Kozloff’s effort here covers work spanning back to the 1970s, largely if not entirely on film, and does something remarkable: It is a story of the presence of man, not in who he is, but what he is: the mundane work we leave behind when we’re not trying. It is not our altarpieces, but our mannequins. Not our poetry, but our graffiti. Not who we wish we were, but who we are—and who we are is detritus.

A compact book of 87 pages, A Carnival of Mimics provides a tight but coherent and clever curation of what must surely be runoff images from Kozloff’s long run of intelligent street photography. The images, even on the occasions when humans of the living, breathing, throbbing, noisemaking variety show up, are effortfully quiet. There’s no sound here but the rustling of pages, the quiet breeze that kicks up the dust (itself a human artifact) from lonely streets.

The nearly 80 images here are set into conversational pairs, visual responses to one another that often provide a question just to answer it: If we, base primates that we are, are easily excited by the thrill of seeing another in the nude, then what is the meaning of the exact same body, in the exact same dimensions, exact same color, exact same form, exact same beauty, if it is exact in every way but for a pulse and a thought?

A Roman amusement park attraction featuring a hulking automaton with which one can play tug-of-war invites another: If the game is the same, why does it matter against whom one plays? If a niche Madonna and a New York woman dressed and painted as the Statue of Liberty —two human characters modeled after real women that for some mean the same thing—does it matter if either one, with their holy hand, might reach out and touch you?

The book is utterly clever, utterly well-executed, and utterly boring. And . . . that’s okay. That’s the point. It’s boring in the way so many of the other things we’ve created in God’s image might be: as boring as church on Sunday morning, as boring as synagogue on Saturday, as boring as meditation on a beautiful afternoon.

It’s important to be bored, and it’s important to sit with work like this and take one’s time with it, think about each image and how it stands alone or how it stands as part of the larger narrative. There is an artistic endeavor here—it is no easy task to assemble something cogent out of the work one has left behind—but also a philosophical one: It provides the chance to sit for a moment with an image and ask ourselves if we are what we write, or what we paint, or what we build, or if—when we can leave such traces of ourselves—if we are, or need be at all.