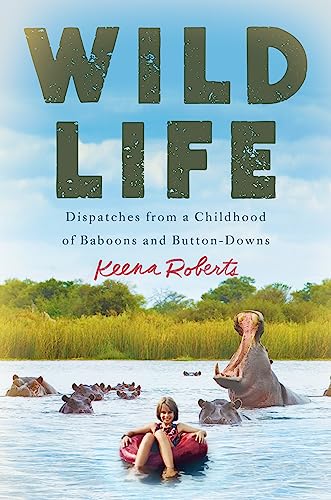

Wild Life: Dispatches from a Childhood of Baboons and Button-Downs

“Wild Life is a page-turner with universal appeal, but a special gift for young girls and women, their brothers, and male acquaintances.”

Wild Life: Dispatches from a Childhood of Baboons and Button-Downs by Keena Roberts is as well-conceived and well-written a coming-of-age memoir. Roberts’ voice is pitch-perfect as she maneuvers us through the streams, rapids, and deep pools of her childhood and adolescence.

Roberts is a Harvard graduate with a degree in psychology and African studies, and a dual master’s from Johns Hopkins University in international public health and development economics. She works for an international market research company examining consumer health in more than 100 countries around the world. In her chosen career path, she pays back the debt she owes Botswana.

Roberts’ childhood and adolescence were far removed from this more conventional post-high school path. Roberts grew up between two worlds, one in the Okavango Delta in north-eastern Botswana and the other in suburban Philadelphia. Her parents are both well-known research primatologists who studied the vocalizations and social interactions of baboons. They worked in the field for six months in the Okavango Delta and fulfilled academic commitments as professors at University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia for six months.

From when Roberts was very young (four) along with her younger sister, Lucy, (two) they were left on a daily basis, at what the family called Baboon Camp in the Delta. Every day, their parents, local helpers and a few international university interns trudged through the “melapa” (grass channels) to find the baboon troop they were studying. Roberts loved everything about the Delta,

“I loved Baboon Camp. I loved the sounds of the birds, the dust beneath my feet, and the buzzing, electric sense of excitement, that anything could happen at any time. I didn’t want to know what my next week, day, hour, looked like. I wanted to feel all the time like I felt when I prowled around the outer edges of the camp, like a coiled spring ready to jump at whatever terrifying or amazing thing, the world threw my way next. I didn’t particularly care if it was an elephant at my tent or a pride of lions by the choo. I just wanted the opportunity to experience it.”

Her first memories of living in a suburban house in Philadelphia tell us that houses never felt like home to her, and in particular, the heating apparatus scared her as elephants in camp never had,

“I distrusted the metal apparatus during the day, but was terrified at night . . . The radiator in my bedroom didn’t seem to adhere to any of the same rules as the rest of the natural world and that made it dangerous. It pinged and whistled all night long and made it hard for me to sleep. Instead of the comforting familiarity of hyenas whooping and zebras calling, in America the only company I had was the bubbling muttering from the metal monster in the corner of my room. . . . Sometimes desperate to hide from the sounds of the wind and the threats of the radiator, I would grab Bundi and crawl under my bed. It felt safer there somehow . . .”

Roberts resented and felt completely out of place in her elementary school in a Philadelphia suburb. Yet she made two lifelong friends there and somehow survived the traumatic feeling of being an alien to her peers, someone who came for a semester and then disappeared into Africa again.

Roberts’ mother home schooled her children in Botswana but in Roberts’ high school years they moved back fulltime to Philadelphia, only returning for the three months of summer, the three months of winter in the southern hemisphere. At Baboon Camp, her closest friend and mentor was one of her parents’ trackers and a reliable presence around the camp. She forged a strong bond with Mokupi, and he taught her well. On their three-month stints in Botswana, she became one of her parents’ most expert assistants undergoing many adventures in the Delta, not least coming dangerously close to death in an encounter with a lion.

Much to the chagrin of Roberts’ classmates she was accepted as a freshman into Harvard. Many things in her life were changing. She was no longer at “home” either in Botswana or Philadelphia. Botswana was becoming more materialistic and westernized, a popular tourist destination for safaris. AIDS was endemic. And one of its victims was Mokupi. His death was a jolt for Roberts, helping her to understand that after all she is an a white, educated, fortunate, American. Her epiphany came on September 11, 2001,

“I knew I was American.” Her identity had been imprinted on her ever since she could walk, but it only became real on the tragic fall morning in New York City. “I had all the trappings of being American, from the clothes to the language, and mannerisms, but actually spent all my time in a world where my identity was both the least and most important thing about me. I didn’t need to be born in Botswana to love the delta as much as Mokupi did, but I could never be Botswanan, and I could never be African. . . . I was part of a different team. And I could feel any which way I wanted to about it—whether it be guilty at the privileges that my race and nationality afforded me or embarrassed at how my home country was sometimes regarded in other places in the world—but the fundamental truth remained: I was American.”

Keena Roberts is a powerful storyteller, and her descriptions strongly evoke both the watery grasslands and natural biota of the Okavango Delta and the mundane milieu of suburban Philadelphia. She has a singular ability to describe her unusual and fascinating coming-of-age story with emotional and psychological truth telling. Wild Life is a page-turner with universal appeal, but a special gift for young girls and women, their brothers, and male acquaintances.