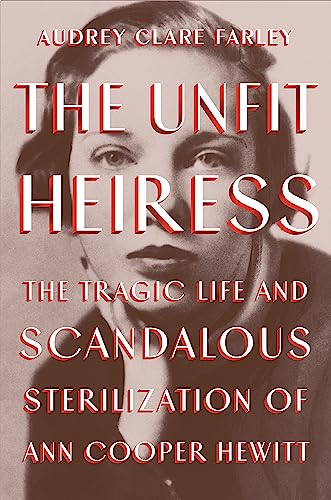

The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt

“In 1883, English intellectual Francis Galton coined the term eugenics (meaning ‘wellborn’) to advocate a selective breeding program among humans.”

Certainly, eugenics was a term that should, and often did, cause anguish, pain, and terror among women throughout the world—not to slight them, it often caused the same emotions and feelings among men.

This is the body of work that author Audrey Clare Farley focuses on in her new book, The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt.

The simple story is that Ann’s mother, Maryon Hewitt, had her daughter declared feebleminded in order to take advantage of the thriving industry of eugenics—a popular plan to prevent the unfit from reproducing. Maryon’s goal was to claim Ann’s inheritance (several millions of dollars) from her father’s (Peter Cooper Hewitt) estate. Hewitt’s will stated that to inherit, Ann must have children. Eugenics became the solution for Maryon—sterilize Ann and there would be no children, and Maryon would control the inheritance.

If the story were that simple, it would hardly be a story, but Farley’s research details not only the life of Ann Cooper Hewitt, but those of Maryon and Peter, as well as the details of eugenics in America, the doctors who practiced it, and the organizers who designed and supported it.

In Ann’s case, one reads with fascination the greed that flowed through Maryon’s life from her youth until her death. An attractive woman who flourished during the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, she saw no reason to behave in any way that did not suit her personal desires. Men flocked to her in droves—some married, some not—and their marital status made no difference to Maryon.

Twice married and divorced when Peter Cooper Hewitt entered her life, she began an affair with him (married at the time). He and his wife had no children, so when Maryon became pregnant, he divorced his wife and the couple married.

Farley explains that Peter, upon seeing his daughter, immediately fell in love with her. Maryon, on the other hand, had no desire to play the mother role, and maids and nannies became an instant success in the Hewitt household.

Maryon started early on, declaring her daughter a misfit and during Ann’s childhood and youth, she spent most of her time in and out of various schools and institutions. At one point Ann was declared a moron by a psychologist who “maintained, the moron population needed to be identified and segregated.” He later “developed the clinical term moron . . . since idiot and imbecile were already in the lexicon.”

Upon Peter’s death, when Ann was seven years old, Maryon found herself in control of Ann’s fortune, and the fact that Ann’s future children played into her inheritance, it became more and more important for Maryon to ensure that children did not happen.

Farley describes Ann’s childhood as lonely and sad without friends. If any maid showed too much affection to the girl, the maid was dismissed and a new one hired.

Maryon learned of the concept of eugenics through the writings of Paul Popenoe and Ezra Gosney who developed the theory that white persons were the savior of America and that immigrants including African Americans, Mexicans, and Native Americans were lower class and their reproductions rates should be curbed, while white Americans should be encouraged to produce as many children as possible . . . that is, unless such white Americans were, themselves, of a lower class. Popenoe and Gosney “desperately needed to find a new idiom to promote eugenics. One that would resolutely convince people of the great danger of allowing just anyone to reproduce.”

Through her research she found two doctors, Dr. Tilton Tillman and Dr. Samuel Boyd, and a psychologist, Mary Scally, who would examine Ann and declare her unfit and conduct the operation.

Farley’s research provides detailed information about the concept of eugenics and its application throughout America, as well as its development in Europe, in particular Nazi Germany.

Throughout the book, Farley also moves back and forth covering Maryon’s actions that lead up to the operation, and the details about the trial that occurred when Ann sued her mother for the unwilling sterilization.

It is clear through Farley’s writing, that eugenics was hailed as a process that would save white America and was highly accepted across the country. Primarily, it was approved by wealthy, white Americans who felt that too many young women had fallen away from the Victorian concept of marriage and motherhood, and these women were unfit to be mothers. The answer to the problem? Sterilization.

During the last quarter of the book, Farley devotes time to the trial itself, and the further activities of both Ann and her mother. Although detailed, the description of the trial and its aftermath felt somewhat less than it should. Perhaps this is due to the coverage earlier in the book.

Maryon is painted as an uncaring mother, and there are moments when her flawed character is clarified. “She may have developed affection for some of her spouses, but each union was clearly a business venture. This attitude enabled her to move on from each failed marriage without a care in the world. . . . she was perceived to be disruptive from the moment she entered the social scene.”

Although throughout the book, we see how Maryon planned to denigrate Ann, especially as the trial progressed. There are moments when we learn more about Ann’s persona as when her personal doctor testified at the trial about her. “She’s read books on Shakespeare, Napoleon Bonaparte, Marie Antoinette, King Lear, Date’s Inferno, and the works of Charles Dickens. . . . My belief is that this young girl has been conditioned during her early formative years by an unwholesome environment.”

Once the trial coverage is completed, and we learn about the turn of events for Ann and Maryon, Farley takes on the subject of the future of eugenics in America and how that fared. The frightening business here is that as recent as 2013 (the California prison system) and 2015 (Nashville, Tennessee), sterilization operations continued to occur. As Farley states: “Long after the heiress and her mother faded from the spotlight . . . Americans have generally continued to believe what the 1936 case decided: that while pleasure may be a universal right, procreation most certainly is not.”

Farley finishes her book with “Remembering Ann.” “After years of estrangement, Ann appeared at Maryon’s graveside in Brooklyn . . .” and “in forgiving Maryon, Ann implicitly acknowledged the dignity and worth of socially outcast women, including herself.”

Farley has presented an excellent case here. The book is fascinating on a variety of levels . . . not just a titillating story about greed, but one that delves further into the human mind and poor judgement, to say the least.