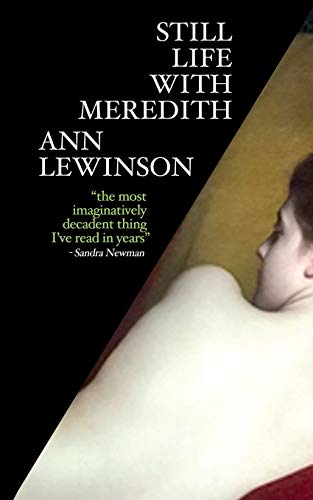

Still Life with Meredith

“To describe Lewinson’s smart, lean, sharp prose as all over the place is praise indeed in the case of this remarkable novella.”

“Call me Ishmael.”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .”

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

And now, to this list of iconic first lines, must be added: “Marie Bonaparte had her clitoris moved three times.”

This will not be the last time this particular body part (not necessarily Mme. Bonaparte’s, and with at least one of them being given lines of dialogue) appears in Still Life with Meredith, the novella by author, playwright, journalist, and film critic Ann Lewinson.

As just a moment’s research provides, the English word “novella” derives from the Italian “novella,” feminine of “novello,” which means “new.” And Still Life with Meredith’s first-person narration does carry the air of the new about it throughout. Told not in chapters but in sections of varying lengths, this slim book of under 100 pages conjures the air of Holden Caulfield talking to readers about his life in an equally conversational tone.

Two young women are living in an apartment that was once a storefront. One of them, Meredith, is away, and the narrator waits for her return. She confesses that she has “not left this room for longer than I care to reveal to you.” She then shares a list of what she does with her time, which includes writing the book readers are reading, reading books on “psychoanalysis, anthropology, and natural history,” and sitting in the corner “picking at the wall-to-wall carpet.”

Meditations on art are always nearby as the narrator spins her stories. She reveals details of her life. Once upon a time she worked at a museum as a chief animal wrangler (not a typo), but then she had to leave her job when she became ill. She now collects disability.

She is a vegan, but she is no friend to the beasts of the air, sea, and field. While animals appear frequently, it is often with significantly less than benign results. If this were not a work of fiction, the ASPCA would have to be called in.

The professional, the creative, the personal, the sexual hold mesmerizing sway in this story. The narrator confides that for a while she was “lurching toward promiscuity,” and she is none too shy about sharing the lurid details of her affairs.

The narrator met Meredith, a rising artist, at the museum. Meredith then invites her to a party. There are details of their relationship, of the narrator’s trip with a guy, and of her current thoughts on a philosopher whose essays she took very seriously in college: “Today Montaigne would be churning out click-bait on a content farm in Hyderabad.”

The narrator’s sturm und drang with Meredith is paramount, as the title aptly indicates. It is a passionate and precarious pairing, and its pendulum swings from one extreme to the other. She has contempt for Meredith being semiliterate, but one senses that this is how she makes herself feel better about her own many self-perceived shortcomings, even as she is clearly besotted with confident, appealing, successful Meredith.

It should be noted that this is not a tale for the squeamish. Violent images of actual events and of events wished for abound, images that are graphic and unique and unusual. Suffice it to say that some involve bestiality and brains literally getting fucked out.

But nonetheless, the squeamish reader should consider taking the brief, intense journey which Still Life with Meredith offers. Lewinson demands an examination by the reader of what is true in life, what is real, what is valid. She presents powerful, witty, shocking examples of a kaleidoscope of experiences and relationships, again, all of it in under 100 pages. This is quite a feat, by any measure.

At roughly the midpoint of the novella, there is a lengthy, detailed meditation on female excision in various countries, at various points in humanity’s timeline, which reads like a history/psychology text. It all sounds barbaric, of course, and Lewinson spares no horror. Then the author brings the story to the west and to modern times, and her point is worth the harrowing journey through time and place to get to the present:

“And today doctors offer something called ‘designer vaginoplasty.’ Some have traded in their scalpels for lasers. They have offices on Fifth Avenue and Rodeo Drive; in France, it’s a covered medical expense. . . . Like a virgin, but more ‘aesthetically pleasing,’ as the ads say.”

Sure, it’s elective, so that’s a big difference, but maybe plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose, and wouldn’t it be swell to know what Marie Bonaparte thinks of this? Let’s hope for a sequel.

And in case there is the thought that Lewinson’s novella is vagino-centric, it’s not just Marie Bonaparte’s clitoris that has center stage. Jesus’s foreskin also shows up, and the piece on the sacred penis takes on the air of a Monty Python routine. The History of the Holy Foreskin as rendered by Lewinson (“bequeathing it to Mary Magdalene, who surely knew from foreskins.”) and performed by John Cleese would be something to see.

To describe Lewinson’s smart, lean, sharp prose as all over the place is praise indeed in the case of this remarkable novella. The author reveals surprises on every page, and brings to mind the cliché about packing a big punch in a little package, or words to that effect.

Lewinson probably could have said it better. . . .