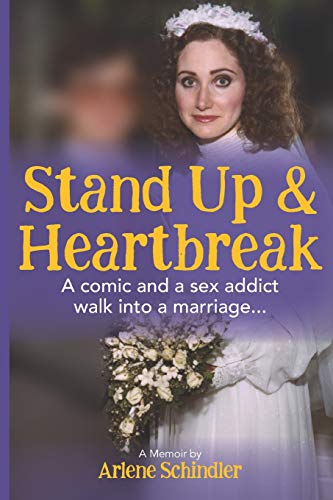

Stand Up and Heartbreak: A Comic and a Sex Addict Walk into a Marriage...

“Schindler’s story, in addition to being a saga of heartbreak and hard-earned wisdom, is a time capsule for Manhattan in the 1980s.”

The writer’s voice has been lauded as a vital aspect of storytelling since . . . well, probably shortly after the advent of storytelling. In Stand Up and Heartbreak, author Arlene Schindler has elevated the role of the writer’s voice and has made it a writer’s conversation.

It is not a conversation without its contentious moments.

Schindler’s story, in addition to being a saga of heartbreak and hard-earned wisdom, is a time capsule for Manhattan in the 1980s. It opens with a young woman living in a studio apartment in Brooklyn in 1981. She rides home on the subway from Manhattan late at night after stand-up gigs of varying degrees of success. On those lonely subway rides, she acts crazy so muggers will be too scared to assault her.

Schindler’s father was a former comic, his dad having made him quit telling jokes to get an “adult job.” Her mother wanted Schindler to continue ballet class, so she can turn from a “klutz into a swan.” The comedy club scene is a man’s world then; Elaine May is her only role model. Schindler works as a temp so she can be available for auditions. “Think American Idol in a blender, with the top off.”

Jokes such as these, by Schindler and also quoted from other comics, pepper the text and offer respite from Schindler’s journey through the hell of betrayal.

Schindler meets her husband at a temp job, where he is her boss. There is not an immediate physical attraction: “. . . he looked like a shrunken, sweaty Clark Kent.” But Rupert (Schindler never indicates if this is a nom de guerre, but one can only hope it’s not his real name) sets out to woo her, and she finds expensive dinners, roses, and tickets to Lincoln Center a fun break from her tight budget.

Dating ensues, along with apartment shopping and the prospect of Schindler finally being able to move to Manhattan. A message from Ted Kennedy (yes, the Ted Kennedy) is left on Rupert’s answering machine (younger readers may need to look up what those were on Wikipedia). A first wife of Rupert’s is mentioned.

And then, when Schindler phones Rupert at work, she hears a secretary screaming at him in a surprisingly intimate rant. The warning signs begin early; those indicators that are always so easy to see in retrospect. Or when you’re not the one in the relationship. Readers may not find themselves alone in yelling at Schindler to “run, don’t walk” shortly after delving into this story.

Schindler’s feelings for Rupert change. “His perseverance and respectfulness charmed me.” When they make love for the first time, the deal is apparently sealed: “This nerdy looking, polite Clark Kent had become Superman in bed. It’s like he was fighting for truth, justice and the American woman’s orgasm.”

Schindler is not reticent in recounting their sex life. Readers will know more about Rupert’s penis than they ever knew they wanted to.

Schindler devotes passages to describing her parents’ relationship. She did not have an encouraging example of what marital bliss could be. Schindler eats to comfort herself from the stress of living in a tense home. “My lifelong journey with food frenzy was a difficult road with a whole series of forks in it. Enough forks for a dinner party.”

Three months after Schindler moves out of her parents’ house, they go on a lavish second honeymoon to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary. “On that trip, they had a gigantic fight. Neither one said, ‘I’m sorry.’ Then they divorced.”

Rupert asks her to marry him, and Schindler decides to accept his proposal. They take a trip to Stockbridge, where Rupert has a cabin in the woods. It is a disaster. Schindler still goes through with the wedding.

Arlene, don’t do it! It’s a bad idea! This will not end well! Run, don’t walk!

On their wedding day, Rupert tells Schindler the truth about his finances. He is not well off, as he had presented himself to be. In fact, he’s just about broke. Schindler realizes, in retrospect and at the time, that she should have run, not walked, but memories of her cousin Kara being a runaway bride (Kara was “still repaying her parents from her secretary’s salary for those 157 rubber chicken dinners”) stop her from leaving. Schindler confides that she would tell her younger self, “Not getting married is worth 157 chicken dinners.”

Their wedding night is spent at the lush Helmsley Palace hotel. Where they don’t have sex. It’s pretty much downhill from there. Rupert has a new job in broadcasting and works nights. Schindler goes back to temp work because of their exorbitant mortgage. Weeks pass, and they don’t have sex.

Schindler starts noticing suspicious withdrawals from their joint checking account and strange items on their credit card bills. They are charges for phone sex lines Rupert is calling.

After nine months of marriage, Rupert suggests they finally go on their honeymoon. Schindler hopes this vacation will lead to hotel sex that will kickstart that aspect of their relationship. Before they got married, Rupert promised her April in Paris, but their lune de miel in the City of Lights was not to be. As a romantic variation from their usual weekends in a lakeside community in Massachusetts, Rupert arranges for a wedding trip to . . . wait for it . . . you guessed it . . . a lakeside community in Maine.

Arlene, don’t go! It’s a bad idea! Call a divorce lawyer! Now!

The air conditioning in the car breaks. The lobster restaurant is out of lobster. Rupert and his bride do make out passionately after dinner, but when she briefly interrupts the impending coitus to go to the bathroom, Rupert is asleep by the time she comes back to bed.

You can’t make this stuff up, which is why this book is a memoir and not a novel.

No spoiler alert is required before announcing that a long road to divorce follows this nightmare of a honeymoon. Along the way, there are lies, confrontations, reconciliations, acts of cruelty, drunk dialing, and a lot of eating of pizza.

Schindler finds an apartment—not an easy thing to do before the Internet; actual ads in actual newspapers and a lot of footwork were involved—and makes a plan to leave while Rupert is at work. When she tells her mother that her marriage is over, her mother asks the rhetorical question of who else will ever marry her.

Yeah, the 80s were a fun time for women.

Schindler shares her journey of introspection and her efforts to make sense of her motivations. Transitions in life are rarely smooth, and Schindler does not coddle herself in hindsight. She is a version of an everywoman of her time. She starts writing advice articles for women’s magazines. She writes a personal ad to put in the Village Voice, the Tinder of its day. And she gets a job at The New York Post, where she originates that newspaper’s comedy column. She also writes articles about sex for Playgirl. Therapy helps her to begin healing, as does joining a support group.

A visit to a comedy club brings her back in contact with Barry, an old friend from her stand-up days. She and Barry begin writing together. He gets a deal to go to Los Angeles and takes her with him.

Schindler’s memoir ends with her new life in Los Angeles. She has a new man, and she’s performing a one-woman show. Rupert is nowhere to be found.

Good job, Arlene! Brava!