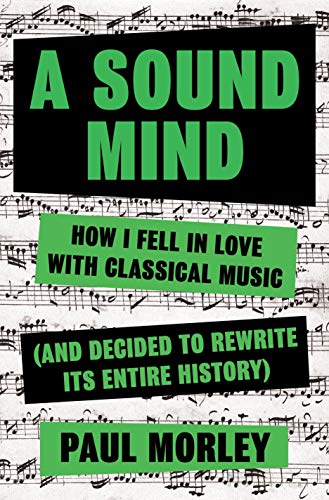

A Sound Mind: How I Fell in Love With Classical Music (and Decided to Rewrite its Entire History)

Paul Morley is fond of the playlist. His new book, A Sound Mind: How I Fell in Love with Classical Music (and Decided to Rewrite its Entire History), is its own playlist, one that includes memoir, history, biography, interviews, and of course, playlists.

What is the goal of a book whose scope is so broad? Morley provides a possible clue: the end is approaching, and he wants to write it all down. “I am on a quest to discover what the final piece of music I will ever listen to will be, which has involved a late-fifties crisis-of-faith crash course in classical music . . .”

Morley--journalist, writer, and producer—spent the majority of his career in pop music, before spending a year at the Royal Academy of Music. He began his year knowing neither how to play an instrument nor the mechanics of musical notation. Morley’s journey was filmed for a BBC documentary, How to Be a Composer. Most classical musicians begin in childhood and spend a lifetime pursuing this genre--Morley learned an astonishing amount of information in his early 50s.

If Morley’s book is a meta-playlist, it includes some fascinating tracks. Among the questions he asks and answers: Unlike classical compositions, why are pop bands more about the brand than the music? Is there a place for music critics now that there are algorithms that can tell you what to listen to next? Why is abstract art sometimes valued in the millions of dollars, when its contemporary--abstract music--is something you can’t own or monetize?

He ties together centuries: he compares the replacement of the harpsichord by the piano in Mozart’s time with the contemporary evolution of the synthesizer. He discusses music listeners now, who are used to hearing the voice “treated, controlled and electrified” and offers a reason why those same listeners might find the operatic voice as scary. “Recorded music perversely created a natural, human sound; to the outsider, the unfiltered, microphone-free opera singer can sound totally unnatural, somewhere between a neutered monster and a distressed fairy.”

Morley travels from composer and performer biographies to an extensive history of the string quartet. Some of his most entertaining anecdotes come from stories of the great conductors. He relates: “(W)hen Klemperer was asked for a list of his favourite composers, Mozart was not on it. When he was asked why, he replied, ‘Oh, I thought you meant my favourite of the other composers.’”

In an overview as broad as the history of classical music, Morley necessarily makes editorial choices based on his tastes. He spends time discussing John Cage, and his use of the prepared piano, his use of silence, and his final organ work titled Organ2/ASLSP—a performance of which is currently underway and scheduled to last for 639 years. Morley’s playlists include a few of his favorite things: “My Top Eleven of Works Commissioned by or Dedicated to the Royal Philharmonic Society Would Be” and “Ravel-gazing: The Playlist Without Bolero.”

Though Morley is naturally limited for composer interviews to those still living, it’s during these interviews that “history” shines. His first interview is with John Adams and his questions are as interesting as the answers. He leads Adams to discuss how he knows when a piece is finished; about branding and Adams’ being labeled a minimalist. He questions Adams about the difficulty of writing melodies and his approach to writing for the voice. For an interview limited to one hour, he extracts a wealth of information about the creative process of a composer and ends with “A Playlist Though Which, Positively, John Adams Flows.”

Since Morley comes from the world of pop as an expert, and to classical music as a more recent expert, there are times when he relies on comparisons that only someone as well-versed as he is in both worlds might understand. Many classical musicians know Frank Zappa’s music but trying to examine it through the lens of others such as Hawkwind, Kevin Ayers, and Tenacious D, something is lost. It’s a good question for the musical writer: how much knowledge does the reader have to come to the table with? How common is a common denominator? Stretching your knowledge is good; being lost at sea isn’t.

For all Morley’s examples of vivid writing—he writes of both Debussy and Ravel being “committed to escaping the force field of Wagner using weapons of delicacy and discretion”—there are also many dense word forests which will leave the reader in a desperate, Faulknerian search for a period. It’s difficult to gain a mental image or a musical understanding of the Gramophone Classical Music Awards from a sentence that begins, “Oddly enough, in its quiet, studious commitment to quality of performance” and only ends 112 words later with “the hardcore fans.”

It may be true that composer Oliver Knussen’s music story was lived “intimately aware of the accidents, coincidences, protagonists, enquiries, insularity, ‘family’ secrets, unlikely meetings, private visions, establishment impositions, erasures, quests, misunderstandings, shifting perspectives, fashions, traditions, counter-traditions, institutional, ideological and personality clashes” but because Morley refuses to choose what to emphasize, these descriptions have the feel of words flung at a wall, with the hope that a few will stick.

His writing is more powerful when he edits. Writing about David Bowie’s final weeks, he says, “The light has all but diminished, your time has passed, but your music has the most power it has ever had.” It’s a sentence that also speaks to Morley’s own awareness of the approaching finish line.