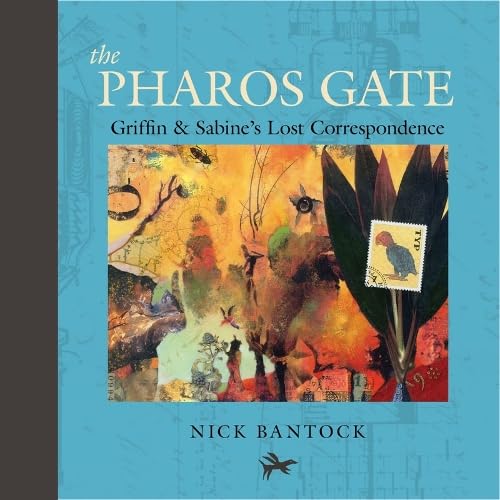

The Pharos Gate: Griffin & Sabine's Missing Correspondence

"You are what I cannot be on my own, as I am all that is missing in you."

The Pharos Gate: Griffin & Sabine's Lost Correspondence is the fourth book in a series of extraordinary epistolary correspondences that take place between two artists. But before we can delve into the latest offering, some 25 years after the publication of the first, we must revisit the past. [SPOILER ALERT: The first three books' secrets are unveiled in this review. But rest assured, nothing will be able to spoil your enjoyment of the devastatingly beautiful art in the series.]

In the first book, Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence, we meet a young woman named Sabine Strohem, a philatologist who lives in the Sicmon Islands, somewhere in the South Pacific, isles so small and insignificant "they are no more than specks of dust in standard atlases." Sabine is a foundling, as she writes, "handed to my father and mother by an old picker who'd found me on the slopes of Pillow Mountain 'bellowing among hot black metal and broken grass.' . . . hungry but otherwise unharmed."

Sabine spends the early part of her childhood attending births with her mother, the island's midwife. Having exhausted that form of entertainment, she turns to her father to accompany him on his search for specimens for his Catalogue of the Islands, a "book that would document every species on the Sicmons." He promises her that she will become the official illustrator of the book when she grows up.

When Sabine is a teen, in a state between sleep and wake, she envisions a work of art being created as "it grew and changed," lines appearing and disappearing. She can see the image being made but not the hand drawing it. This goes on for years with hundreds of images of art, until one day she discovers that the art that she has been envisioning is that of Griffin Moss, the owner of a one-man postcard company. She tracks him down and sends him a hand-drawn postcard opining on one of his drawings that he has never shown anyone. And that is how the love story begins.

Sabine's own handdrawn postcards and envelopes feature beautifully rendered naturalistic representations of creatures, flora, and fauna, hand-rendered maps, an anatomical illustration of a handmaiden surrounded by primeval figures, fantasy females and a skeletal man—a veritable collage of fancy. Is she to become a muse? Is her male doppelganger to become hers?

Griffin, of course, writes back. Within a few correspondences, he finds out that Sabine shares his sight. He is intrigued—"I've a million questions. Am I the only one you see? What form does your sight take? How come I can't see you?"—as well as slightly freaked out. Through letters—handwritten and typed, cursive and printed, that we get to remove from their hand-drawn envelopes and postcards, front and back, including stamps!—we learn that Griffin was the child of well-meaning bibliophiles. "Our house was a temple to The Book. We owned thousands, nay millions of books. They lined the walls, filled the cupboards, and turned the floor into a maze . . . they were our demi-gods."

Griffin's lonely childhood is interrupted when his parents are mowed down by a newspaper van. It is then, at age 15, that he is sent to live with his mother's stepsister Vereker, a potter, in Totnes, Devon. Griffin adores her: "I would have made her my idol if she'd let me. Instead, I became her apprentice." Her death decimates him, and he falls into a deep depression. In his mind, he's been alone ever since. "Meeting" Sabine changes his life yet again.

Their letters and postcards become more intimate until Griffin suffers a sort of breakdown and cuts her off. "I've started to think I am in love with you. Before it takes me over it has to stop. Goodbye."

The book ends with: "These postcards and letters were found pinned to the ceiling of the otherwise empty studio of Griffin Moss. Griffin Moss is missing." This engenders somewhat of a conundrum: Sabine has already decided to come to London to see him.

Book two, Sabine's Notebook: In Which the Extraordinary Correspondence of Griffin & Sabine Continues, Griffin, fearing he is going mad, has left the country on a quest. He starts in Dublin and goes to Florence, Greece, and Egypt, "an exercise in walking backward." In all these venues he continues to write to Sabine, who by now is staying in his studio on Yeats Street in London. He visits Japan where he writes: "I was clinging to logic like a life buoy. Now, in the flick of an eye I'm trying to follow intuition." It is as if he is turning himself inside out to flush reason from his system and infuse it with more art-friendly intuition.

Griffin continues to the bushmen, then Brisbane, all the while recounting every bit of his travels to Sabine in his finely drawn, colorful, telling postcards and letters with their handdrawn envelopes. The delicious and forbidden joy of this particular type of voyeurism is not to be discounted as a powerful part of the experience of reading these books.

It turns out that in addition to visiting Griffin, Sabine has an errand to run in London. The publisher of her father's Catalogue of the Islands is expecting the next installment, which she chooses to hand deliver instead of trusting it to the post—an odd prejudice since this entire correspondence has been entrusted to the post worldwide, even in areas where Griffin has to receive Sabine's letters and postcards en restante—at a general post office in whatever large city the voyager travels. It is during Griffin's extended, six-months-long voyage abroad that Sabine admits: "I have loved you since I was 13, when I first saw your hand moving across that paper."

Perhaps it is this admission that gives Griffin the courage to finally decide to go to the Sicmon Islands to visit where Sabine grew up. But on the voyage over, his boat capsizes and he nearly drowns. He ends up in a hospital to recover, then on to Paris where he sends Sabine a postcard promissing to be home on the 23rd.

He returns as promised on the 23rd. But the studio is empty.

The art on the final postcard showcases a skeleton rendered in black and white atop an atlas page with a winding key next to what looks like piece of an ancient manuscript, notations of a chemical compound called a methyl group, a turtle as if to signify the Galapagos where evolution was "discovered," and a baby gryphon on the hand-drawn stamp. What does it all mean?

The question is not answered in Sabine's final postcard, which finishes the book: "I received your Paris card. I waited, but you did not return on the 23rd. I waited until the 31st, but you did not return. What happened? Where are you?"

Book three, The Golden Mean: In Which the Extraordinary Correspondence of Griffin & Sabine Concludes, begins with a few big questions. Evidently, during the six months that Griffin is gone and Sabine has lived in his studio, no one, including his landlady, has seen anyone coming or going. Indeed, there was even an overlap of seven days, from the 23rd to the 31st, that they were both occupying the same physical space, but still they do not meet.

Is Sabine a ghost? Is Griffin a nutter? How is this possible?

As Griffin puts it, "this overlapping of time and space seems like we're living in parallel universes. Do you think we are separated for life, each unable to exist in the other's presence?" In search of some solace, Griffin goes to visit Vereker's dear friend Maud in Devon. Once there, he walks over to Vereker's old place and finally confronts his grief over her death. It is a relief, but it does not bring him any closer to resolving the mysterious divide that keeps the lovers apart.

The art, meanwhile, that drives all these words, is fantabulistic. We are treated to a wolf-bear-kangaroo-like furry creature holding an ice-cream cone stuck with pins, beautiful stone formations in the woods, an Asian flute player, a black and white etching of a woman whose gaze veers off the page, bouquets, armadillos, you name it—all rendered in wild colors and textures so finely wrought they feel three-dimensional.

While still in Devon, Griffin receives a postcard from the Sicmon Islands, but from a man who calls himself Frolatti and who claims Sabine sent him. Apparently he somehow knows about the "form of communication" between Griffin and Sabine, and he wants information. A professional curiosity, "Nothing personal, I assure you."

When Griffin informs Sabine about this latest turn of events, Sabine tells Griffin that indeed she did not send Frolatti, who, it appears, has been stalking her and her family, trying to get infromation from them about what is happening between the two writers and artists. Worse, Sabine reveals, "Something is happening to my vision. When I see you drawing now, it's all out of focus. I must take action. But what do I do? Being apart from you is unbearable." Griffin agrees: "We have to do something. Anything. I cannot stand by and watch the door between us close. We need to find a way to come together or be lost to one another forever. . . . I know this to be true."

Their polarity is now more than just divisive, it is a harbinger of what might happen if they do not finally meet face to face. Sabine suggests middle ground. They agree to meet in Alexandria, at Pharos Gate. But not before the third book ends with: "For some years nothing was heard from either Griffin or Sabine, until a young doctor in Kenya received an unusual postcard from a stranger. . . ." The postcard is a photo of a newborn.

Now, finally, we are at The Pharos Gate: Griffin & Sabine's Lost Correspondence. The conceit of this book is that it fills in the time after they decide to meet up in Alexandria and their actual meet date. Sabine is still on the islands. She is worried about Frolatti, still around, still threatening and manipulating, and how he will react after she's given him the slip.

As she writes, "I'm certain he'll do anything to stop us." Neither can understand why Frolatti is so obsessed about their relationship, but they know he does not want them to physically meet. "Perhaps," writes Sabine, "he believes our uniting represents something more significant than empathetic souls coming together." It is as if Frolatti is the devil.

Griffin cannot wait. He leaves for Spain because he feels its "magnetic pull." There he will wait until Sabine gets on her way to Alexandria. Griffin writes to Maud, Vereker's old friend from the countryside, and tells her what he is up to, filling her in on the secret love affair he has been having with a woman named Sabine. Maud, in turn, writes to her friend Frances, who lives in Alexandria, asking her to look out for Griffin while he's there, but not to tell him that she (Frances) knows anything about his extraordinary relationship with Sabine.

Finally en route to the meeting place, Sabine reaches Papua New Guinea safely. And here we learn that Pharos Gate, according to Sabine's adoptive father, "was one of the city's earliest structures" and "the ancients had revered the gateway as a portal to the underworld." So far, so good. But there's a catch: "The first Alexandrians believed that whilst the arch could be walked through by anyone, only those who wished for completion could step beyond the mortal realm and find safety from their enemies." Frolatti, be damned!

Frolatti, however, will not be averted. He writes to Griffin again: "You will not meet. Your world and hers will always circle one another." But it is as if the stronger the menace, the harder the lovers fight to come together. Somehow, through their resolve to meet, Sabine's vision of Griffin's art is restored.

Discussions of art and the act of creation throughout are conflated with emotion and the internal search for self. As an artist in Spain, Griffin sees his task as an artist "more akin to that of a flamenco dancer drawing up the fire through his body and watching in awe as it grows upon the surface before him." He is clearly getting closer to uniting the disparate senses of himself as a man on one side and an artist on the other. For him to be both, he must be one united.

Frolatti is getting closer to the lovers, having gone so far as to having an "associate" track down Maud, who experiences him as having a "barely human" mein. Murderous starlings, rabid human-eating wild dogs, an unfriendly monkey—it is as if Frolatti, like the devil, morphs into malevolent creatures determined to stop the lovers in their journey toward one another. Time now starts ticking loudly to the climax.

Griffin describes his evolution as an artist and a man as an experience both exquisite and annihilating: "I feel like I am only now coming into full existence. It is as if my real self has been secretly growing within. It's a strange evolution, sometimes a warm unfolding, at other times a painful crunching of bone and twitching of muscle."

Sabine replies, "I believe, Griffin, that you and I were born inside each other, like changelings inverted within a prism. You have always needed someone to love and cherish you, so you imagined me . . . But that frightened you. . . . What you did not understand was that the person you had imagined already existed."

As we get closer to Alexandria and the Pharos Gate, the art becomes wildly variant. Photos and photorealistic faces and places, crumbling architecture, fairyland flora, skeletal insects, Balinese writing, colorful cryptography—all that and more inhabit the handmade correspondences flying back and forth, illustrating the moodiness of both of the artists.

Upon Griffin's arrival in Alexandria, Maud's friend decides to trail Griffin to Pharos Gate to make sure that nothing untoward happens to him. She tiptoes behind him, hiding out in the open, watching what happens next—which you'll have to read about when you get your own copy of the immensely talented Nick Bantock's latest book, The Pharos Gate.