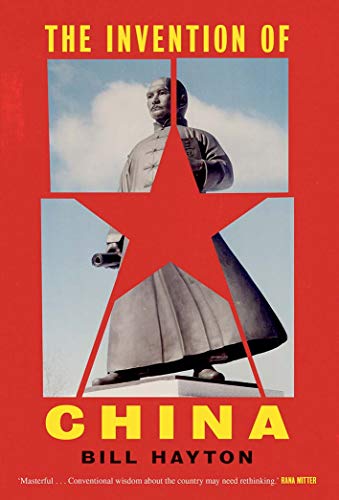

The Invention of China

The Invention of China is a very readable book that will educate the general reader and provide experienced sinologists with a bevy of insights and fresh perspectives on a growing military and economic power. Author Bill Hayton is a researcher at the Chatham House think-tank in London and a correspondent for the BBC. He also wrote The South China Sea and Vietnam. He knows East Asia well and writes not just with verve but with a quest for scholarly precision that satisfies the editors of a major university press.

The Invention of China illuminates the fragile foundations on which PRC president Xi Jinping is building his expanding realm. Hayton argues that “China” and its 5,000 year of unified history is a myth created just over one century ago with a political agenda that persists to this day. “Modern China’s ethnic identity, its boundaries, and even the idea of a ‘nation-state’ are innovations from the late nineteenth and early twenties centuries.” Western notions about sovereignty, race, nation, history, and territory became part of Chinese collective thinking.

Today’s idea of a Chinese nation dates from around 1900 when Sun Yat-sen returned from schooling in Honolulu and, with a few other young men, called for a modernizing Chinese polity to replace the moribund Qing empire. This vision energized both Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists as they struggled to lead this new entity.

Hayton warns that “we cannot understand the present-day problems of the South China Sea, Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and ultimately China itself, without understanding how this modernizing vision came to be adopted by the country’s elite and how future problems were embedded with it.”

The idea of nationhood in most countries is rooted in a myth. How people perceive and “construct” reality may differ radically from how things in fact are. For example, climate-change deniers go their ways no matter how the climate changes. People act on the basis of what they think they see in the world around them.

Belief in a common national identity requires an active imagination. What ties join a New York office worker with a Texas cowboy? Or a farmer or computer technician in Harbin with a factory worker in Guangzhou? A myth of national unity is probably a necessary but not sufficient condition. Even France, home to the earliest “nation-state,” was a virtual Babel until after the 1789 Revolution. At least six million people then used a local language (derided as a patois) different from Parisian French. The post-1789 leaders of France used political indoctrination as well as raw power to press its diverse peoples and cultures into a somewhat unified “nation.”

Xi Jinping’s “dream” of a rejuvenated and restored China is about 30 years old. It arose in the 1990s and early 21st century as the Chinese Communist Party strove to legitimize its rule after its leaders massacred demonstrators for democracy in Tiananmen Square in 1989. To maintain their rule, PRC politicians opened the economy so ordinary people could improve their material living standards. But people do not live “by bread alone” and so the leadership sought to supplant Communist mythology with nationalist pride.

India also has a billion-plus population and nuclear weapons, but few other countries fear India as they do China. What makes China different is its increasing repression within its borders and its continuing pressure to expand those borders. As Hayton concludes: “A country that believes it has a superior civilization, that its population evolved separately from the rest of humanity and that has a special place at the top of an imperial order will always be seen as a threat by its neighbors and the wider world.” Xi Jinping, Hayton says, is trying to build “national-socialism with Chinese characteristics”—Chinese fascism.

Hopes that bringing China into the world of commercial and scientific exchange would generate a willingness to prosper in peace with the international community now look naïve. The Invention of China challenges policy-makers and the public: How to deal with a powerful revisionist state determined to increase its influence in Asia and the world?