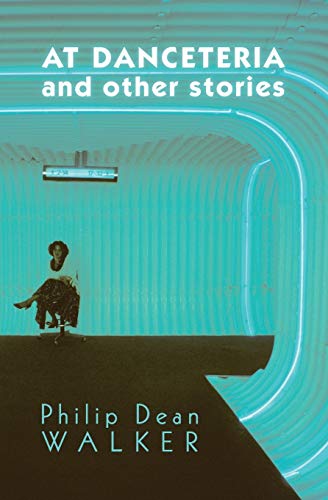

At Danceteria and Other Stories

“Walker’s stories intersect the tipping point when big city gay life went from carefree hedonism and glitzy self–indulgence to the moment when self–satisfied habitués of the demi–monde began to witness the wide scale decimation of their generation.”

“Men, women, children, dogs—they all stopped what they were doing in order to look at him.”

This is how Philip Dean Walker describes an arresting beauty in “The Boy Who Lived Next to The Boy Next Door,” one of seven stories in this slim volume of highly imagined tales that bring dead celebrities back to life, place them in unexpected settings, and time warp the reader back to 1980, a time of high camp and existential danger.

Walker’s stories intersect the tipping point when big city gay life went from carefree hedonism and glitzy self–indulgence to a moment when self–satisfied habitués of the demi–monde began to witness wide scale decimation of their generation.

We are of course in the first days of AIDS before it was even called that, a time when an ageing Rock Hudson could innocently indulge the mirror: “Whenever he’d catch his reflection somewhere . . . he would pause to see if he could locate that younger man he had once been, the one in all the movies.”

Of Princess Di who finds her entourage and her royal self at a leather bar, the anonymous narrator explains that “This is what it took to have a life: fake itineraries, large sunglasses, escaping through secret exit doors.” Jacqueline Kennedy at The Anvil, a notorious sex club at the time, engages in the rapier wit then common, an acid–tongue repartee that cut competitors to size while serving as a shield of self-defense.

Walker‘s stories rely on relentless name dropping: Truman, Calvin, Liza, Andy, Halston—the latter we are told who is actually “Roy Halston Frowick from Des Moines.” The put-down echoes the bitchy disdain that exuded from Studio 54 during the real Halston’s cocaine-fueled reign. “If you’re not famous then you better be extremely good-looking, wearing something extraordinary, or be someone worth screwing.”

Meanwhile, Mick Jagger had his palm read to see if he was bisexual.

For boomers who actually lived through the era these stories depict, Walker’s chronology is occasionally off. A name–drop of “Savile Row underwear” perhaps references Calvin Klein whose underwear models, plastered on enormous bilboards in Manhattan, were stellar commodities at the time. But a Savile Row spoksman confirms that the company didn‘t brand underwear until 2008.

Likewise, the “hot gay flu” that came to be known as AIDS was not recorded by the Center for Disease Control until 1981, sometime after the “advanced stages” cited here. The anachronism in no way diminishes the author’s take on lookism in which “Hot gay flu attacked only gorgeous guys until suddenly it didn’t.” And then comes the heartbreaking reversal: “The average looking, the homely, and the downright ugly” became desirable. Once rejected by the disease, “now we, the rejected, were the chosen ones.”

Looking up the “Steve Carrington” and “Ewing” actors of Knotts Landing and Dynasty that Walker describes to see how hot they really were, one discovers that both characters were each played by two different actors. The original “Steve Carrington” was played by Al Corley, a doorman at Studio 54. Corley was paid to tell people to their faces that they weren't good-looking enough to be let in. So Steve Carrington was actually cruising Manhattan at the time and fucking below his station for real. This makes Mr. Walker‘s fiction more accurate than he may realize.

Walker’s reimagining of the 1980s is ultimately clever and original. His humor is sharp, penetrating, and entertaining. One wishes there were more of it throughout. One wonders at the end, too, what the meaning is in having these dead celebrities coming back to life.