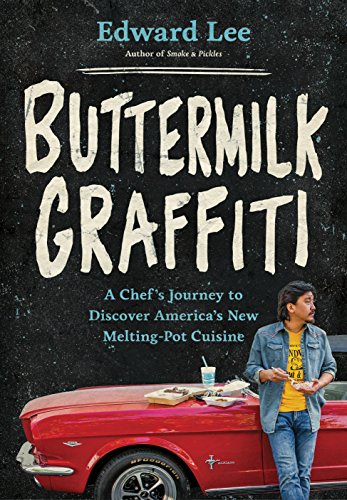

Buttermilk Graffiti: A Chef’s Journey to Discover America’s New Melting-Pot Cuisine

The writer as gastro-tourist guide is nothing new. Waverly Root, an American foreign correspondent in Europe, took readers on a tour of French regional cuisine 60 years ago when he wrote the classic work, The Food of France. The purpose of his work was to not only describe France’s culinary delights, but to get at the soul of the French by way of their food.

Sixty years on, Edward Lee, an acclaimed chef, writer and Emmy award nominee for his role in the PBS series The Mind of a Chef, takes the role of gastro-tourist guide to the next level, decoding the American landscape in his new work, Buttermilk Graffiti.

Lee, a second generation Korean American who began his cooking career in a New York diner while earning his undergraduate degree in English at New York University, takes us on a mind-bending tour of undiscovered and little known places in the American culinary landscape. What readers think they know about America is sure to be challenged in Buttermilk Graffiti, an altogether eye-popping collection of essays that crisscrosses the United States and pulls back the curtain on what’s really being cooked in America today—and who is doing the cooking.

Lest readers need yet another reminder of Barrack Obama’s insistence at the 2004 Democratic National Convention that “[t]here is not a black America and a white America and Latino America and Asian America — there's the United States of America,” Buttermilk Graffiti should put that debate to rest.

In 16 essays that feature different culinary traditions, Lee shows us that America is still the melting pot it always was and (hopefully) always will be. What is surprising about this book, though, is just how pervasive the notion of the melting pot is in our country.

In Clarksdale, Mississippi, for example—undoubtedly a deep Red part of the country—Lee is in search of soul food and is told that the best soul food can be found at the local Chinese restaurant where there are three cooks: a Chinese man, a Mexican man, and an African American woman.

He also discovers an entrenched Lebanese Christian population that settled in Clarksdale generations ago when they were fleeing persecution in their country. They brought their culinary traditions with them and now, in the deep South of Clarksdale, Mississippi, you can go to a diner by the name of Chamoun’s Rest Haven, opened in 1947 and eat Lebanese dishes like kibbeh, a kind of meatball. In Clarksdale, though, the kibbeh is made with beef instead of the traditional lamb because, well, people in Clarksdale eat beef.

Think about it, in Clarksdale, Mississippi, alongside all the locals from every background imaginable one can sit down and eat Lebanese food made by Lebanese Americans whose ancestors arrived speaking Arabic and French, and soul food in a Chinese restaurant. Only in America.

Also in America, as it turns out, the best pastrami sandwich doesn’t come from the Lower East Side in Manhattan, but from Shapiro’s Kosher-Style Foods in Indianapolis. Not only that, but the delicatessen has been continuously operating since 1905 by Jewish immigrants fleeing the pogroms in Russia.

And in Lowell, Massachusetts, there are more Cambodian restaurants than in New York City. The same goes for the number of Korean restaurants in Montgomery, Alabama. In Houston, Lee takes us to Sabo Suya Spot where people line up early to eat Nigerian cooking made by a former Nigerian prince who moved to Texas in 1997 to work as an agricultural engineer. And so on, and so on, all across America (recipes included—though with obscure ingredients they are not likely to be tried in the home kitchen).

As Lee writes about his experience in Clarksdale, Mississippi, “This is America. Maybe not the white picket fence version we are used to seeing, but the one that exists in every town just beneath the surface, embodied by the diversity in the labor economy.”

In the end, Buttermilk Graffiti is as much about politics as it is about food. Speaking as a chef who owns and operates two restaurants in Louisville, Kentucky, he writes, “This is the first time I’ve done anything like this. I’ve always held the opinion that a restaurant should be a place free of politics . . . [but] I have begun to feel that, as chefs, we no longer have the luxury of being neutral.”

All across America, we are learning about each other through food. “Food is trust and trust is intimacy.” To eat a kebab at an Iranian restaurant in Dearborn, Michigan during the month of Ramadan is to come to a better understanding of their culture. “I could taste the devotion, which is everywhere in the culture . . . I’ve been eating hummus and tahini and falafel all my life, but for the first time, I understood why these foods feel so deeply enriching.”

Near the end of the book, Lee sums up his two-year journey across America: “for every insight I gain from learning about another culture, it brings me closer to the one I find myself in. This project, this entire process of discovery and adventure, is about trying to find my own America and where I belong in it.”

Using food as the way in, Buttermilk Graffiti is a timely and important work that reminds readers that America’s melting pot is alive and well in the most unexpected places. And, that we all belong.