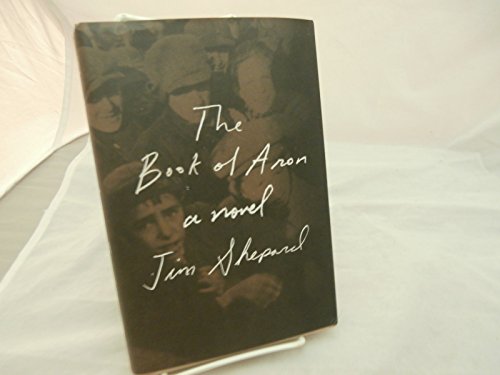

The Book of Aron: A Novel

“powerful.”

The Book of Aron is narrated in the flat, unemotional voice of a Polish-Jewish boy who is ten years old when World War Two begins. It is a story told almost without adjectives in one unadorned declarative sentence after another.

And that understatement is one reason this short Holocaust novel is so powerful.

Moreover, author Jim Shepard—a National Book Award finalist who has explored other tales of misfit youth and evil venues in his 10 prior works of fiction—dared to create a narrator who is often unlikable and even cowardly. A common refrain in the book is that “Aron thinks only of himself.”

(To be fair, the Holocaust made it impossible for most adults—let alone children—to exhibit much selfless courage.)

From his earliest childhood in a small border town, Aron is constantly doing the wrong thing. He breaks bottles; he lets the neighbors’ animals loose; he can’t learn to read. “My father said they should have named me What Have You Done,” he writes.

When Aron is six, his family, including two older brothers and a younger brother with tuberculosis, moves to Warsaw, where his father gets a job at a cousin’s fabric factory. But life doesn’t improve markedly: The younger brother dies, sending the mother into depression.

Of course matters turn far worse after the Nazis invade. Aron’s father and surviving brothers are deported, and his mother dies of typhus.

Almost by accident—mainly because his small size enables him to squeeze into tiny spots—Aron becomes part of a gang of teenage smugglers in the Warsaw Ghetto. They include his only real friend, Lutek, whom he met before the war; the pretty and wealthy Zofia and her friend, Adina; and Boris, a tough character whose family is assigned to live in Aron’s apartment and who immediately declares that “he looked forward to becoming our leader” in the gang.

For a while, Aron shows some unexpected backbone by resisting pressure from Lejkin, one of the miserable breed of Jewish collaborator-police, to report on his colleagues. But Aron is not made of hero material, and he finally caves on the promise of information about the whereabouts of his father and brothers.

After that, the betrayals come again and again. Two of his comrades are killed because of him.

For many victims, understandably, the Holocaust was simply a world where you scrabbled for survival in any way possible. Yet it could also be a world of unspoken mutual support, like Aron’s gang before his treachery.

The novel’s strongest example of unselfish sharing in the midst of evil is Janusz Korczak, a real-life Jewish pediatrician and advocate of children’s rights who somehow maintained a large orphanage in the ghetto through a combination of begging and personal connections.

Korczak takes in Aron and even selects the boy to accompany his daily scavenging expeditions. Perhaps the doctor sees some humanity buried deep in the flawed youth.

Indeed, as the novel unfolds, more and more hints of Aron’s pain and other emotions subtly emerge between the lines of his just-the-facts reportage.

After one of Lejkin’s attempts to blackmail him, Aron says, “I stopped and tried to rewrap the cloth strips around my shoe. I couldn’t believe I was crying about a shoe.”

The uninflected voice can feel a bit sing-songy after 250 pages, but it generally works. More problematic is the character of Korczak, who becomes increasingly preachy.

In a stunning finale to an already powerful book, Shepard breaks a traditional pact between author and reader.

Agatha Christie famously shattered a different tradition in her 1926 classic, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, when the narrator himself turned out to be the murderer. The Book of Aron’s daring final twist works partly because ambiguous endings are usually better than neat packages, and partly because the Holocaust itself broke so many assumptions about human behavior.