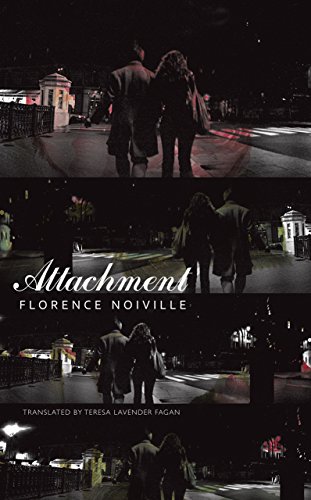

Attachment: A Novel

“The brevity of text perforce creates a poetic compression.”

With her superb biography of Isaac Bashevis Singer, Isaac B. Singer: A Life, and her moving novel, The Gift, the French writer, Florence Noiville, via the magical passport of translation, has seamlessly entered into American literature. And now we have her latest work, a riveting new novel, Attachment, about a remembered love affair between a 17-year-old high school student and her 47-year-old teacher.

From the opening lines of this enchanting work the reader knows he has entered a special world, keenly observed by the author and made palpable through Noiville’s magnifying lens into the human heart and the characters she creates.

“How many ‘me’s are there? Do you ask yourself that question too? There are so many fragments, all those mismatched ‘me’s that look at one another without understanding. The one who speaks and the one who writes, the one who loves and one who reasons, the one who is passionate and the one who doubts. . . .”

The book is narrated by both the heroine, Marie, and her daughter, Anna, and their voices alternate throughout this compact book. The teacher is known only as H., which causes mystery and consternation for Anna, when she discovers a bundle of letters that her late mother, Marie, had written to H. Now Anna seeks to discover who this man is or was.

Nowadays, with newspapers and magazine articles depicting love affairs between teachers and students—of all ages and all combinations, most of them under the rubric of “abuse”—we have here in Attachment a sensitively rendered consensual love story that is remembered by a woman of 49.

And where in most of these teacher/student relationships the older teacher is usually the one to lure in a younger student, in Attachment Marie admits that she initiated the relationship.

The teacher H. reads to her selections from the great Biblical love story, “The Song of Songs,” with its undercurrent of eros that both teacher and student attempted to cloak by deflating its sexuality and accenting its spirituality. (Indeed, the major religions have done precisely this with “The Song of Songs” in order to camouflage or even erase the eros.) Nevertheless, the young heroine feels the excitement of the forbidden as she hears H. reading those alluring verses from that classical love song.

H. cleverly uses the literary works he assigns to enhance this relationship. When the class studies Moliere’s The Misanthrope, the teacher tells his students to focus on a certain scene. For the next class, he assigns Marie to sit next to him, and they read out loud the love dialogue between the hero and the flirty young heroine. And in one of her letters to H., Marie naively wonders if he chose that scene on purpose.

Years after the affair, in another of her letters to her teacher (the reader does not know if those letters were ever sent or not) Marie exclaims: “You told me ‘I love you’ in the language of Moliere, and in our own private theater of love that would remain the ‘primordial scene’.”

The short passages written by mother Marie and daughter Anna are sometimes no longer than a page, sometimes just a couple of pages. After we are introduced to the affair by Marie, it is only when we read the first entry by Anna that we learn about a tragic accident that occurred when Anna was only 14, a fact that prompts a dramatic shift in our understanding of this story.

At one point in Attachment Anna writes that her mother preferred not wearing glasses even though she was nearsighted. “She needed that delicate blurriness.” Whereas Marie needs glasses, Florence Noiville uses her own special lens—the magnifying lens I mentioned before; perhaps even better, a microscope—to enter the world of her protagonists with such minute detail, revealing, enlarging every cell of her and H.’s turmoil. Note how carefully Florence Noiville describes love, the 17-year-old Marie in love with her teacher’s voice which “caressed me, it brushed my neck, enveloped me in its rhythm.”

Anna finds these letters that her mother had written many years earlier to her former lover. She learns that Marie had compared herself to the older teacher in parallel with the affair that the future Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt (author of the book on Eichmann, The Banality of Evil) had with her philosophy professor, the pro-Nazi Martin Heidegger, and for which she was much criticized in the Jewish community for consorting with “one of the enemies.”

Aside from the Moliere scene there are other references to literature, which also play a role in this short, pungent tale, from Moliere to the Song of Songs, from Nabokov’s Lolita to other old-young affairs, books cast their beneficent shadows onto Noiville’s novel. Indeed, literature itself can very well be considered a protagonist in this narrative.

In Attachment we also meet—through Anna’s entries—Marie’s mother, Suzanne, and others who add perspective to the tale. And the brevity of text perforce creates a poetic compression. And so, despite its 125 pages, the fascinating and richly drawn characters within are vivified as though portrayed in a work four times as long.

Attachment is beautifully translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan.