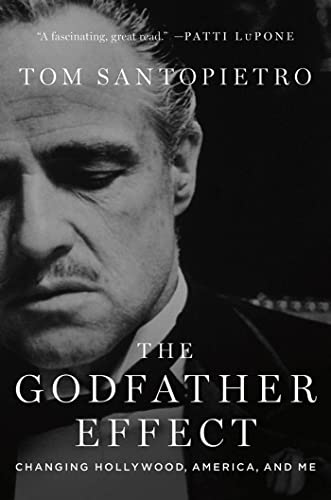

The Godfather Effect: Changing Hollywood, America, and Me

“. . . despite its failings, The Godfather Effect is generally engaging. Even though the author adds little to the existing corpus of Godfather commentary, he capably weaves together the memoirist elements, the history, and the analyses of the formal and thematic aspects of the films. For those readers unfamiliar with this material (and there must be some), Tom Santopietro’s book will provide a useful introduction.”

Forty years ago a young Italian American director named Francis Ford Coppola revolutionized the gangster movie with a three-hour–long, ultraviolent (for the times), and unabashedly ethnic film about a Sicilian Mafia patriarch and his family. Two years later, he followed up this landmark with a sequel that was even better, richer, and more trenchant in its portrayal of organized crime as a metaphor for American corporate capitalism.

These films, chronicling the rise and fall of la famiglia Corleone, have attained mythic stature in American pop culture; decades after their release, they continue to fascinate and enthrall. That the third and seemingly final installment of the Corleone saga failed to equal its predecessors, and indeed is generally regarded as a turkey, has done nothing to dim the luster or enduring popularity of the first two.

So much has been written about The Godfather films (and their source, Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel) that one wonders: Is there really anything new that can be said about them? Books about the films constitute their own literary subgenre; a brief and by no means comprehensive list includes The Annotated Godfather, The Godfather Papers and Other Confessions (by Puzo), The Godfather Family Album, Beyond the Godfather, The Godfather Trilogy, How to Really Watch The Godfather, The Godfather Companion, The Godfather Legacy, The Godfather and American Culture, The Godfather in Pictures, and, in the interest of full disclosure, this reviewer’s An Offer We Can’t Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of America.

Give credit then to Tom Santopietro at least for being unintimidated by the challenge of planting something fresh in this over-tilled terrain.

The Godfather Effect is a series of related essays on the films, their impact on Italian Americans, including the author and his family, and the larger society. But too much of the book is secondhand, rehashing existing literature, popular and scholarly.

There’s the account of the troubled making of the first film (Coppola’s battles with Paramount Studios over everything from the casting of Marlon Brando and Al Pacino to the expensive location shooting in Sicily); the potted history of Italian immigration; the familiar narratives of Italian American family life (the lavish Sunday dinners make their predictable appearance), and an overview of the Mafia’s origins. None of this will be news to anyone who has read any of the voluminous literature on these topics.

Mr. Santopietro is the son of an Italian American father and a WASP mother; in Godfather terms, that makes him a Corleone and an Adams (the surname of Michael Corleone’s wife Kay). His father’s family came from Pontelandolfo, which Mr. Santopietro passes off as a generic southern Italian town, not even identifying its regional location. (It’s in Campania, north of Naples, and not the Corleones’ Sicily.) Mr. Santopietro’s forbears, like many from Pontelandolfo, immigrated early in the 20th century to Waterbury, Connecticut. They, like countless other southern Italian immigrants, fled a life marked by poverty and oppression. Once settled in America, his grandparents opened a grocery store, and his father, one of three sons, became a successful physician. His Anglo mother, civic-minded and equipped with a master’s degree in social work, was well known in the community for her volunteer work.

Mr. Santopietro portrays his mixed family as warm and loving, yet there were culture clashes between his mother, with her progressivism and WASP reserve, and his father’s side of the family, whose purported peasant fatalism she deplored.

Throughout The Godfather Effect, Mr. Santopietro compares his Italian family’s experiences to those depicted in The Godfather, minus the criminal element. (His grandfather, like Vito Corleone, came to America by himself, as a boy.) He observes that those experiences, of immigration and assimilation, are common to most Italian-descended Americans, accounting for the shock of recognition they felt upon viewing the first film when it was released in 1972 and their lasting affection for it decades later.

But Mr. Santopietro’s treatment of Italian American ethnic history is attenuated, overly reliant on just a few sources and mainly on La Storia, a good but not definitive popular history published 20 years ago. A quick review of his sources reveals that he hasn’t engaged with the larger body of literature on both Italian Americans and organized crime. And although he admits that his Italian is virtually non-existent, that doesn’t excuse his repeated use of the term “paesanos,” which doesn’t exist in Italian. A more knowledgeable writer would have used the Italian American “paisans” or the Italian “paesani.”

In his analyses of the films, he recaps what’s been written elsewhere, especially in Harlan Lebo’s Godfather Legacy. His observation that The Godfather “did nothing less than help Italianize the United States” was made and developed in depth by Chris Messenger in his excellent The Godfather and American Culture. And virtually everyone who has written about the films has noted that Coppola likens the Mafia to corporate capitalism, that the director, in adapting Puzo’s novel, drew on Shakespearean tragedy, and that real-life gangsters not only embraced the films but modeled their language and behavior on the Corleones.

Mr. Santopietro’s discussion of gender and sexuality, key thematic motifs throughout the entire Corleone saga, is cursory and unsatisfying. But even worse, he cops out when he writes about one of the most famous scenes in the first film: Vito Corleone chastising the has-been singer Johnny Fontane for weeping like “a Hollywood finocchio.” The Don was saying that Fontane was behaving like a faggot, which is the meaning of “finocchio.”

Tom Santopietro is openly gay, yet he never acknowledges that when discussing the significance of the scene and his reaction to it. But wouldn’t being a gay man influence one’s reaction, not only to this one scene but to the films in general, which are basically about violent and sexist heterosexual men? And later, when he mentions that some of his relatives are unhappy that he will not carry on the Santopietro name, he offers no explanation. Elsewhere the author is quite candid about his family and himself, so why the evasiveness?

Still, despite its failings, The Godfather Effect is generally engaging. Even though the author adds little to the existing corpus of Godfather commentary, he capably weaves together the memoirist elements, the history, and the analyses of the formal and thematic aspects of the films. For those readers unfamiliar with this material (and there must be some), Tom Santopietro’s book will provide a useful introduction.