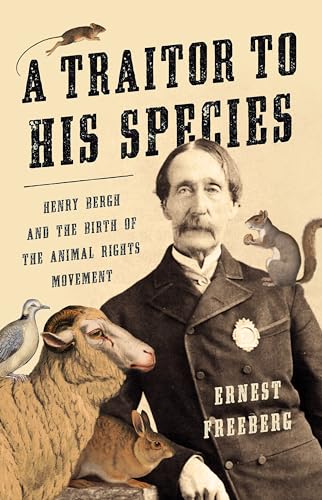

A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement

“Highly readable, A Traitor to His Species ably details the ‘uncomfortable debate about the proper balance between animal rights and human interests . . .’”

Here comes Henry Bergh (1813–1888), the eccentric and controversial activist who advocated public flogging of animal abusers in 19th century New York City. A self-described “terror, for doing good,” he didn’t care much for dogs and cats but battled in court for them as well as snakes, pigeons, and raccoons.

Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), the nation’s first animal welfare organization. He was one of several noted reformers who sought to eradicate the wrongdoings of 19th century Americans. Others included censor Anthony Comstock, self-proclaimed “weeder in God’s garden” who created the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (1873), and Carrie Nation, hatchet-wielding temperance advocate. Carrie’s greeting to tavern keepers: “Good morning, destroyer of men’s souls.”

These were troublemaking do-gooders driven by religious beliefs to tackle the urban ills of a growing post-Civil War nation.

In A Traitor to His Species, University of Tennessee historian Ernest Freeberg offers a full, brightly written, anecdote-filled account of the career of Henry Bergh, a dapper, humorless New York City socialite and heir to a shipbuilding fortune. Bergh dropped out of Columbia College, enjoyed a carefree five-year European tour, then accepted a diplomatic appointment as secretary of the U.S. legation to Tsarist Russia. There, in the streets, he witnessed cruelty to animals. Bergh experienced an epiphany.

He hated human cruelty.

In 1866, at age 53, after a failed literary career (poetry and playwrighting), Bergh began a two-decade run as New York’s animal rights champion. Empowered by passage of the city’s new law—the first in the nation against animal cruelty—he and his agents roamed the streets, arresting New Yorkers engaged in deliberate acts of cruelty and sadism. The abusers included teamsters who beat horses, boys who set fire to cats for amusement, and owners who abandoned worn-out livestock to die of starvation.

That work pleased the public. But Bergh faced opposition and ridicule when he attacked “his society’s long-standing assumption that animals were property, objects with no rights that humans were bound to respect.”

For instance, he challenged the right of teamsters to overwork trolley horses, the cruel methods used to ship livestock, the caging of exotic animals in zoos, and the use of animal bodies in human health. For years, he was ridiculed for defending the rights of lobsters, chicken, and rabbits. His sad eyes, droopy mustache, and melancholy mouth made him an especially attractive subject for satiric cartoonists.

In one early legal confrontation, in which he tried to protect green turtles from pain and mistreatment during their transit from Florida to New York’s Fulton Fish Market, he declared, “The blood-red hand of cruelty shall no longer torture dumb beasts with impunity.” The courtroom drama drew enormous publicity (Bergh’s goal) and helped spur the nationwide growth of the animal rights movement.

Freeberg offers absorbing stories of Bergh’s conflicts with notables of the day, from Cornelius Vanderbilt, who used hundreds of old, disabled horses to pull trolleys filled with commuters on his streetcar line; to showman P. T. Barnum, who had been terrorizing rabbits by caging them with boa constrictors at his American Museum, and later became good friends with Bergh.

One can only imagine what butchers in slaughterhouses thought when Bergh wrote them: “The eye of the Almighty Creator of all is upon you.”

Bergh had mixed successes. He drove popular working-class blood sports—cockfights and rat baiting—underground but was unable to halt the upper-class practice of shooting pigeons as they flew by the thousands from traps. Most important for the long term, Bergh inspired anticruelty laws and the spread of ASPCA chapters to every state.

Highly readable, A Traitor to His Species ably details the “uncomfortable debate about the proper balance between animal rights and human interests, and the animal suffering at the core of the American economy.” It’s a discussion that continues to this day, says the author, over issues like modern factory farming.