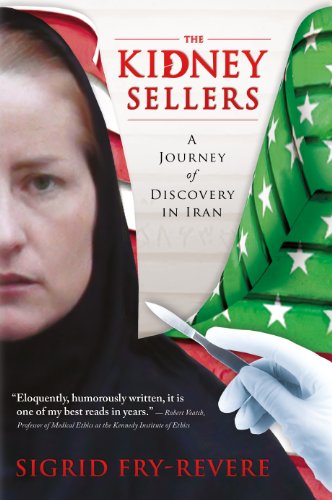

The Kidney Sellers: A Journey of Discovery in Iran

“Fry-Revere makes stark comparisons between the kidney donation program in the U.S. and Iran. Dialysis is portrayed as a very poor alternative to kidney transplants . . . Most U.S. patients die without receiving a transplant, while in Iran 16 months is the average waiting time to receive a transplant.”

The Kidney Sellers relates the very personal journey of Sigrid Fry-Revere as she sought the Iranian solution to a problem that has plagued the U.S.: the kidney donor shortage.

Just the title, The Kidney Sellers, can prompt controversy. As a means of overcoming the kidney shortage, Dr. Barry Jacobs proposed a program of compensated donors, but this proposal sparked such an outrage that a law (The National Organ Transplant Act of 1984) was enacted prohibiting payment for organs. Also, the anti-Iranian climate in the country largely negated any discussion of an Iranian solution to the kidney shortage problem.

The transplant community hoped that cadavers would provide an adequate supply of kidneys but the author very convincingly pointed out that cadavers can never provide an adequate supply. The kidney shortage has resulted in a black market even more exploitative and damaging than the Jacobs proposal.

Fry-Revere is eminently qualified to write this book. After receiving a ph. D in patient-care ethics she worked as the director of bioethics studies at the Cato Institute. She began to study the merits of compensated organ donation and organized a forum where experts debated the issue. She was astounded to observe that each speaker had strong opinions on Iran and its system of compensated organ donation without ever having been there.

Fry-Revere left her job at the Cato Institute, since the Institute, for political reasons, did not want her to continue researching Iran’s kidney market. She created the Center for Ethical Studies, and initiated the Solving the Organ Shortage project.

Fry-Revere’s research made it clear to her that she would have to travel to Iran to find answers. An organ transplantation conference to be held in Shiraz, Iran, provided an opportunity. Her hope was to use the conference as a launching pad to research the Iranian system of organ procurement through interviews with staff, donors, and recipients of kidneys.

She had the good fortune to arrange for an Iranian nephrologist, Dr. Bastani, to make arrangements for a lecture tour and interviews. She decided not to ask the Iranian government for permission to do research or interviews, as they could have restricted her research or even denied her request.

Fry Revere’s friends and family tried to discourage her from making the trip, and the prospect at times appeared dangerous and absurd even to her. Iran was considered hostile to Americans, and she would have had to travel around a country where women’s rights were limited.

In The Kidney Sellers, Fry-Revere shows considerable strengths as a nonfiction writer. She is a keen observer of details in surroundings, events, and people. The reader is caught up in her personal drama of anxieties, impressions, and reactions to events. The history, culture, and current political climate of Iran is interspersed liberally throughout the book so that the reader can better understand why Iranians are motivated to act as they do and why the current kidney donor system was enacted.

Fry-Revere was able to study the Iran solution through a wide cross-section of the country, visiting six cities. Each city had very different characteristics in physical setting, ethnicity, and implementation of the donor system.

The Iranian government has set up a program where a relatively small payment is given to donors, but additional payments from recipients are typically negotiated. Contrary to the U.S., cadavers are seldom used for kidney donations.

Fry-Revere provided a good cross-section of donor characteristics. Financial need was the primary reason, although each donor had their unique story. Religious leaders determined that the compensated kidney donation program can be considered in terms of exchanging gifts instead of a commercial transaction so does not violate Sharia law.

Fry-Revere makes stark comparisons between the kidney donation program in the U.S. and Iran. Dialysis is portrayed as a very poor alternative to kidney transplants, as dialysis only removes about 10% of toxins from the blood, and patients live on average only four years. Most U.S. patients die without receiving a transplant, while in Iran 16 months is the average waiting time to receive a transplant; as well, transplants are less successful in the U.S. since patients can be very debilitated by the time transplants are available.

After Dr. Fry Revere’s return to the U.S., two of her good friends with kidney disease died awaiting kidneys. She states that she does not claim to know how to solve the U.S. organ shortage and suggests starting a small pilot project of compensated donors to see how it works out.

In the Notes section at the end of the book, Fry- Revere describes the extensive background information that she compiled on the Iranian project and gives an excellent commentary and resources for further study.