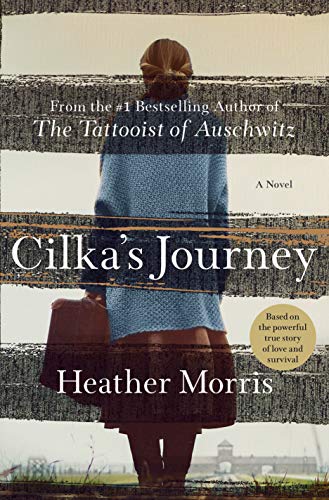

Cilka's Journey: A Novel

“Heather Morris reminds us about the human side of the Holocaust and helps us remember with her fine storytelling.”

Heather Morris, author of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, has done it again. She has written a compelling novel based on a real-life person who survived Auschwitz Birkenau and in this case, ten years in a Russian Gulag in Siberia.

Morris wrote this story at the urging of Lale Sokolov, the tattooist whose story she told in her first book. Sokolov knew Cilka Klein at Auschwitz where she was sent in 1942 when she was 16 years old. Based on her interviews with Sokolov and others, as well as her own in-depth research Morris tells Cilka’s story with deep compassion while avoiding the trap of sentimentality. Some of her characters are imagined; others are based on real people, but importantly, the story she tells is real. It is a story of a beautiful, brave, skilled young woman who survived three years in Birkenau and ten years in a Soviet labor camp.

It is not revealing too much to say that Cilka managed to survive the concentration camp by becoming the semen vessel, or sex object, for two Nazi officers who repeatedly rape her. She stays alive by allowing unspeakable humiliation and abuse while being the kapo, the Jewish guard, in the building to which women are sent to their death, including her mother.

After the war, she is sent to the Siberian Gulag because the Russians see her as a German collaborator. There she suffers further rape, hard labor, and despair. But she also survives, again because of her beauty, her courage, her skills, and her will to live. She bonds with the women in her hut, finds work in the camp hospital where a kind woman doctor inspires and protects her as she proves her abilities and befriends others who work there. Interspersed with the events in the Siberian camp are Cilka’s flashbacks of her time in the concentration camp, a device that helps us understand, just barely, the horrors of her time there.

The important thing to remember is that Cilka was a real person, and the main elements of her story are true, including the fact that like Lale Sokolov, she found love in captivity. Released from the Stalinist labor camp five years early when Khrushchev came to power, she and her lover/husband went on to live a long life together in Kosice, Czech Republic. These are the facts. But the story is about Cilka and how she survived 13 years of hell.

Her spirit and will, summoned for all those years, is captured in a conversation with the doctor who is her mentor, once Cilka can finally begin to talk about what has happened to her. “I gave in,” Cilka tells the doctor, full of shame and guilt. Yelka replies, “The first day I saw you I felt there was something about you, a strength, a sense of self-knowledge that I rarely see. And now, with the little you’ve told me, I don’t know what to say except that you are very brave. . . . You have shown what a fighter you are. My God, how have you done it?”

It’s a question every reader will ask as they imagine rocking Cilka in their arms to comfort her.

Morris’s epilogue, which concludes with two women lifting their glasses to the Yiddish toast, “L’Chaim” (to life), her concluding notes, Additional Information, and Afterword do much to flesh out the story of the real Cilka and to explain the history and the politics of the time in which her story takes place.

“Stories like Cilka’s deserve to be told,” Morris writes. “She was just a girl, who became a woman, who was the bravest person Lale Sokolov ever met.” No one is better than Heather Morris at telling stories like Lale’s and Cilka’s. But she gives the last word to Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who also survived the Gulag. He dedicated his book The Gulag Archipelago to “all those who did not live to tell it.. And may they please forgive me for not having seen it all, nor remembered it all, for not having divined all of it.”

No one who hasn’t been there can imagine what Lale, Cilka, Solzhenitsyn, and so many others like them endured. Heather Morris reminds us about the human side of the Holocaust and helps us remember with her fine storytelling.