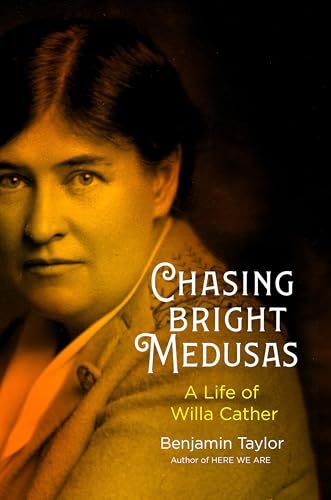

Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather

“If she had not chased those bright Medusas, 20th century American literature would have not had one of its most beautiful voices.”

There have been a half dozen biographies of Willa Cather since her death in 1947, most notably substantial studies of the writer’s life and work by James Woodress and Hermione Lee. Benjamin Taylor’s trim account of Cather’s life belongs on the same shelf with those heftier narratives.

Taylor argues that the raison d’etre for his book is that “the lifting of the last . . . stricture against quoting from [her letters]” has been lifted. But ultimately what is closer to the truth is his admission in the prologue that his biography “arises from a debt of love.” Chasing Bright Medusas is surely a love letter to a writer who deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as her male contemporaries—Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dos Passos, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald.

Born Wilella Cather in 1873 in Back Creek, near Winchester, Virginia, she moved with her large family when she was nine years old to Red Cloud, Nebraska, a locale that, along with the Southwest, became the locus of her imagination and the heart of her fictions.

When she was 30 years old, she visited her brother in Winslow, Arizona, and as Taylor points out, “She was captured for good and all by the harsh beauty of the Southwest.” In 1890, when she was 16 years old, she graduated from Red Cloud High School, the class valedictorian, the first in a class of three. After she graduated from the University of Nebraska, she became a full-time journalist, working as an associate editor for Pittsburgh’s Home Monthly magazine.

But in 1897, after a year of writing about colicky babies and Angora cats, she decided to leave the magazine and write a books column for the Pittsburgh Leader newspaper. For the next decade or so—a time she described as “the years of frenzy,” she produced over one million words of journalism. During that time, she met Isabelle McClung, the great love of her life, the wealthy and well-traveled daughter of a prominent judge.

There has been much critical and biographical discussion of Cather’s lesbianism and how it influenced her creative work, and Taylor addresses the issue with a complex clarity: “Willa saw herself as exceptional rather than homosexual. But that she was homosexual is obvious, astounded though she would have been to know it. . . . Sexual nature is what she intended to rise above.” She was an anti-modernist Modernist, a writer who focused on what Faulkner would have called the “old verities”—the quiet heroism of her prairie heroines and Southwestern priests, the principles of valor and loyalty, faith and purpose.

In 1901 she took up high school teaching, diligently performed that job, and wrote, too. In 1906, she was invited to New York City by S. S. McClure, the founder of McClure’s Magazine, one of the most prominent magazines of the day. After a few years of freelancing for them, she left teaching to become the magazine’s editor. Around this time, she met Edith Lewis, and their domestic partnership lasted their lifetimes.

A few years later, when McClure’s Magazine went into financial receivership, Cather saw her longed-for opportunity to shake off the responsibilities of editing and devote herself completely to her fiction. On the brink of her 40th year she published O Pioneers!, her second novel but the one in which she discovered her true subject, the American West and its pioneer people. Soon after, she published My Antonia, guaranteeing her fame.

In 1915 she traveled with Edith Lewis to Mesa Verde, Taos, and Santa Fe, and these became pilgrimages for her that led eventually to two of her greatest novels: The Professor’s House (1925) and Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927). In these novels—and in the greatest of her fictions—landscape is always a central character, and the themes of loyalty and love, the potency of memory, the complicated beauties of art, and the power of compassion, honor, and faith became her touchstones.

In her masterpiece, Death Comes for the Archbishop, Father Latour says, “Where there is great love there are always miracles.” The priests in that novel seem to stand in for artists. For them seeing is all. For Cather, art is religion. Cather, like her priests in Death Comes for the Archbishop, sees the “miraculous in the ordinary.”

The title of Benjamin Taylor’s wonderfully uncluttered biography alludes to what Cather grappled with as a writer. In a letter to her friend and fellow writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Cather wrote, “It is a strange to come at last to write with calm enjoyment and a certain ease, after such storm and struggle and shrieking forever off the key. I am able to keep pitch now, usually, and that is the thing I’m really thankful for. But Lord—what a lot of life one uses up chasing ‘bright Medusas,’ doesn’t one?” If she had not chased those bright Medusas, 20th century American literature would have not had one of its most beautiful voices. Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner emphasized the emptiness and loss of meaning in the modern world. Cather focused on faith and nobility. For her, “everywhere, God is in the details.”