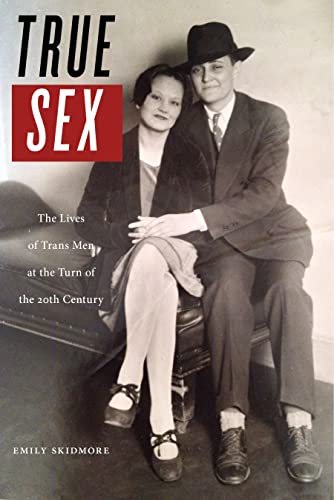

True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Historians, like archeologists, play an invaluable role uncovering all-but-forgotten people of the past, thus helping provide a better picture of the present. Emily Skidmore’s study, True Sex, is one such study, a valuable contribution to the growing academic field of transgender studies.

Skidmore, an assistant professor of history and gender studies at Texas Tech University, clearly undertook exhaustive “archaeological” research to undercover the stories of the 18 “trans men” she profiles. “I refer to my historical subjects as ‘trans men,’” she notes, “because they chose to live their lives as male even though they had been assigned female at birth.”

She carefully tracked the relevant biographic information for the people she chronicles through the newspapers of the day, both local and national, as well as census, court, marriage, and other records. She focused her study on trans men who lived in the U.S. during the fin de siècle era (1876–1936), who often married a woman, and lived mostly in small towns and rural communities scattered throughout the country. Most revealing, the people she chronicles came to public attention because they were “outed” as a result of an autopsy following their death, a marital scandal or a prosecution. How many others lived lives of trans anonymity is outside the scope of this study.

Skidmore offers a three-fold critique. First, she provides well-drawn—and sympathetic—profiles of the compelling trans men considered; second, she offers a critical assessment of the press of the day and how it helped foster a new morality, one grounded a medico-legal notion of pathology; and third, she engages in an ongoing critique of her field of study, LGBT scholarship.

Three of the trans men she considers are representative. Frank Dubois lived in Waupun, WI, and was married to Gertrude Fuller. Known as a hard-working fellow, he was outed in 1883 when his former husband, along with their two children, arrived in the town in search for their departed wife and mother. Dubois was revealed to be anatomically female.

George Green was married to Mary Biddle. After moving from one small town to another, the couple settled in Ettrick, VA, where George was accepted as a hardworking husband. The discovery of his “true sex” was met not with denunciation, but rather with approval because he had lived such a conscientious life.

Murray Hall was a New York man-about-town: a successful bail-bondsman, a Tammany Hall politician, married, and the father of an adopted daughter. He regularly voted and served on city juries. While short in stature, with a whiskerless face and a “boyish” voice, he was a regular at local pubs, drank his share of whisky, and flirted with women other than his wife. However, upon his death in 1901, an autopsy revealed he was a she, a “female husband” as such trans men were then labeled.

At the heart of True Sex is the question as to how a difference—i.e., personal representation—became a deviance, how a form of modern female (mostly white) gender “passing” was a deviance, an illegal practice? She discovered the subjects of her study through carefully newspaper database searches and each of the case studies is grounded in a rigorous critique of the local and national media coverage.

Skidmore places the trans-man stories she considers as examples of the changing nature of U.S. sexual culture. It is represented in the redefinition of marriage, an increasing use of the state to police formally private matters (e.g., sexual practices, marriage), and demographic changes recasting big and small cities alike.

She repeatedly demonstrates that media coverage in the national press often differed significantly from local reports. The national, big-city press, and news services exploited the story, making the story of the outed trans man more salacious, often threatening to national security. Local coverage tended to present the person as part of the community, accepted as a fellow citizen, often a hardworking, good husband and family man.

True Sex is a richly suggestive work that brings to life ordinary people who lived rather extraordinary lives. However, Skidmore does herself an intellectual disservice by not discussing why she did not consider what can be called “trans women,” the “MtF” or the “male wife.” Unfortunately, she did not locate an African American trans man for her study. The two non-white trans men she considers—Jack Bean (aka Babe Bean), the daughter of a Mexican father and white mother, and Ralph Kerwineo, the daughter of an African-American father and “mixed-race” mother—both “passed” as South American.

Most peculiarly, she repeatedly falls back on the questionable notion that one’s sex at birth is “assigned.” Unfortunately, to be assigned assumes something as agent, and Skidmore never identifies the source of the “assignment.” Unless she is deeply religious, human life is a roll-of-the-dice.

Robin Marantz Henig, writing in the January 2017 National Geographic, outlined the scientific aspects of gender, notes: “Sex differentiation is usually set in motion by a gene on the Y chromosome, the SRY gene, that makes the proto-gonads turn into testes. . . . Without the SRY gene, the proto-gonads become ovaries that secrete estrogen, and the fetus develops female anatomy (uterus, vagina, and clitoris).”

One of Skidmore’s most refreshing, if unacknowledged, insights is her repeated use of such terms as “perhaps,” “it’s possible” and “it’s impossible to know the motivation.” While an intellectually contesting academic, she recognizes the limits of her revealing study. More scholars should give up the conventional, male-academic pose, the authoritative voice, and admit the limits of their knowledge.