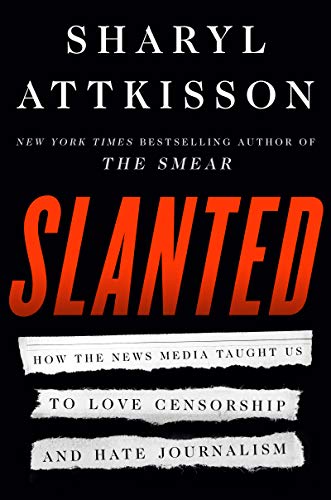

Slanted: How the News Media Taught Us to Love Censorship and Hate Journalism

“Slanted is Attkisson’s most recent effort to expose the biases and corruption in the mainstream media even as she laments ‘the death of the news as we once knew it.’”

Sharyl Attkisson once worked for the mainstream media at CNN and CBS News. In 2014, she left CBS after it became evident to her that the news executives there were increasingly hostile to her reporting. In her news stories and investigative reports, she did not follow the accepted liberal “narrative.” The narrative as established at CBS News, she came to believe, was more important than facts.

Slanted is Attkisson’s most recent effort to expose the biases and corruption in the mainstream media even as she laments “the death of the news as we once knew it.”

She started working at CNN in August 1990, shortly after Iraq invaded Kuwait. Back then, she writes, CNN was mostly concerned with reporting “just the facts,” though it did have a few opinion shows like Crossfire. “We news anchors,” she recalls, “wouldn’t have dreamed of slamming political figures or giving editorial monologues about them during our news reports.” It was a “fact-based information operation,” despite being owned by “ultra-liberal billionaire Ted Turner.”

Attkisson praises Turner for being a pioneer of cable news and for understanding that “the mission of his news network would be undermined if the news product were not perceived to be generally neutral.” The rest of Attkisson’s book is about how all of that changed, not just at CNN but throughout the mainstream media—print and broadcast.

Her book reads like an indictment which charges the mainstream media with liberal bias, lack of journalistic ethics and standards, and complicity in modern “wokeness”—the shaping, promoting, and enforcing “narratives” about political issues, political leaders, and what used to be called “news.”

Modern journalists and their editors are not content to report the news; instead, their goal, she says, is to tell readers and viewers what to think. And to punish those who refuse to toe the line by ridiculing their work, leveling personal attacks on them, and even censoring their “objectionable” views and opinions.

Attkisson believes that “we’re in an Orwellian environment,” where the modern media filters information to ensure that “only the ‘correct’ view is presented.” “Right now,” she warns, “versions of history and current events are being written and revised in real time according to what powerful interests wish them to say.”

The mainstream media and social media platforms, she writes, “‘curate’ or censor information on the news, ban certain facts, declare selected viewpoints illegitimate, cleanse social media of particular accounts, and judge people and events of the distant past using today’s evolving and controversial standards.”

A good portion of the book reviews the media’s coverage of news events, such as mass shootings (where the common narrative is about gun control), severe storms and environmental disasters (where the cause is invariably climate change), allegations of inappropriate conduct toward women (women are almost always to be believed), Islamic terrorist attacks (they have nothing to do with religion), and police shootings of black men (invariably attributed to “systemic racism”).

Attkisson believes that the mainstream media (the three major television networks, cable news except Fox, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and a few others) lost even the pretense of objectivity in their openly hostile treatment of President Donald Trump. This treatment goes beyond mere liberal bias to an intense hatred for the man and a determination to destroy his presidency.

The media’s anti-Trump bias was most clearly revealed in the “Russia collusion” stories where Trump and his allies were portrayed as guilty until proven innocent, even after the Mueller investigation came up short on proof of any wrongdoing. “For more than two years,” Attkisson writes, “reporters and pundits insisted Trump had conspired with Russia to win the presidency, even though there was no publicly available proof of any such thing.”

Attkisson at one point refers to her book as an “autopsy” that proves that the death of the news was an act of suicide. The goal of the mainstream media, she writes, is not to inform but rather to cause the masses to “lose the ability to form independent thoughts.” Think what they—“the information dictators”—tell you to think or face the consequences—ostracism, censorship, ridicule, or worse.

Yet Attkisson concludes her book on a hopeful note. There are still good journalists and reporters, she says. And there are alternatives to traditional news outlets—and she provides a list of them in the book’s closing pages. The list includes mostly conservative papers and websites, a few investigative reporters, and some liberal journalists that Attkisson continues to admire. They help keep us “free from the grip of political and corporate interests or social activists who increasingly seek to limit what we may know and say.” Let us hope she is right.