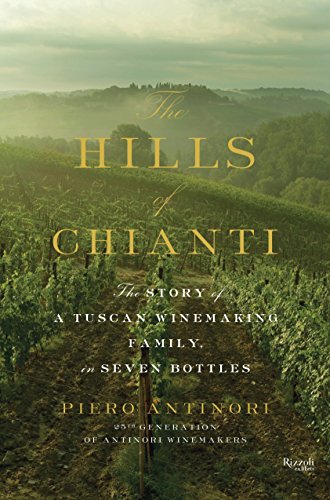

The Hills of Chianti: The Story of a Tuscan Winemaking Family, in Seven Bottles

“He tells the story of how his company had to separate from a beverages industry partner, because the latter was too worried about the quarterly bottom line. Very gradually and carefully, Antinori grew his company by making great wines, and by expanding to make more of them. The story is well told in the book.”

From Vergil’s Georgics (1st century BCE):

Non eadem arboribus pendet vindemia nostris,

90 quam Methymnaeo carpit de palmite Lesbos;

sunt Thasiae vites, sunt et Mareotides albae,

pinguibus hae terris habiles, levioribus illae,

et passo Psithia utilior tenuisque Lageos

temptatura pedes olim vincturaque linguam,

95 purpureae preciaeque, et quo te carmine dicam,

Rhaetica? Nec cellis ideo contende Falernis.

Sunt et Amineae vites, firmissima vina,

Tmolius adsurgit quibus et rex ipse Phanaeus;

Argitisque minor, cui non certaverit ulla

100 aut tantum fluere aut totidem durare per annos.

Non ego te, Dis et mensis accepta secundis,

transierim, Rhodia, et tumidis, Bumaste, racemis.

Sed neque quam multae species nec nomina quae sint,

est numerus; neque enim numero conprendere refert;

105 quem qui scire velit, Libyci velit aequoris idem

discere quam multae Zephyro turbentur harenae,

aut ubi navigiis violentior incidit Eurus,

nosse, quot Ionii veniant ad litora fluctus.

[Not the same is the vintage that trails from trees of ours, and that which Lesbos gathers from the branch of Methymna: there are Thasian and there are pale Mareotic vines, these meet for a rich, those for a lighter soil; and the Psithian more serviceable for raisin-wine, and the thin Lagean that in her day will trip the feet and tie the tongue, and the purple and the earlier grape; and in what verse may I tell of thee, O Rhaetian? yet not even so vie thou with Falernian vaults. Likewise there are Aminaean vines, theirs the soundest wine of all, for which the Tmolian and even the royal Phanaean make room; and the lesser Argitis, that none other may rival whether in abundant flow or in lasting through length of years. Let me not pass thee by, O Rhodian, well-beloved of gods and festal boards, and Bumastus with thy swelling clusters. But there is no tale of the manifold kinds or of the names they bear, nor truly were the tale worth reckoning out; whoso will know it, let him choose to learn likewise how many grains of sand eddy in the west wind on the plain of Libya, or to count, when the violent East sweeps down upon the ships, how many waves come shoreward across Ionian seas.]

From the 17th century poem, “Bacco in Toscana” (Bacchus in Tuscany):

Là d’Antinoro in su quei colli alteri,

Ch’han dalle Rose il nome,

Oh come lieto, oh come

Dagli acini più neri

D’un Canaiuol maturo

Spremo un mosto sì puro,

Che ne’ vetri zampilla,

Salta, spumeggia e brilla!

E quando in bel paraggio

540D’ogni altro vin lo assaggio,

Sveglia nel petto mio

Un certo non so che,

Che non so dir s’egli è

O gioia, o pur desio:

[On Antinoro’s lofty-rising hill

(Yonder, that has its name from Roses)

How could I sit? How could I sit, and fill

Goblets bright as ever were made

From the black stones of the Canajuol cru

How it spins from a long neck out,

Leaps, and foams and flashes about!

When I taste it, when I try it

(Other lovely wines being by it)

In my bosom, it stirs, God wot?]

—Francesco Redi (L’Aretino)

Il vino, specialmente in Italia, è la poesia della terra. (Wine, especially in Italy, is the poetry of the earth.)

—Mario Soldati

Nothing Italian is ever closely defined. I have a Neapolitan cookbook from 1926 which is filled with amazing local recipes, but none of the amounts to use or cooking times are quantified (“prendi un bel pollastro . . .” take a nice-sized chicken . . . cook it for a long time in a hot oven . . .) . . .

Real pizza is made with buffalo mozzarella and the sauce of tomatoes ripened until they are very sweet, and fresh leaves of basil, but, in my home city, I can go to a machine on the street which will serve me a pizza from a slot in its side in which the ingredients are all semi-artificial, and for which one of the toppings is pineapple.

And, if you should ever try to make “spaghetti all’ aglio, olio e pepperoncino” (with garlic, oil, and hot pepper)—good luck trying to figure out when to put the hot peppers in, or how hot to make the oil. Yet my friend from the Abruzzo does it all without a second thought.

So when Mario Soldati, a writer whose concerns were political and social, hardly gastronomic, writes that “wine is the poetry of the earth,” he is expressing a kind of fundamental Italian truth in the manner of the country.

In fact, there is a long tradition linking the soil of different places to the wines that are made there. It goes back at least as far as the Romans, but there is good reason to believe it arrived in Italy with the Etruscans—very enigmatic people, the Etruscans, but they apparently did place a high value on making wine.

The Roman poet Vergil, on the other hand, we know a lot about, and his first long poem, the Georgics, was dedicated to a revival of Italian agriculture. The second book is all about growing vines, and, you can see that he makes a close link between the wine and where it comes from. There is wonderfully artistic poetry in the Georgics about man and nature, and the relationship of the divine, the natural, and the human. Wine, for Vergil, was a means to link up the spirit of place with the spirit of the people who lived there.

The tradition is ancient and strong in Italy. The 17th century poet and scientist, Francesco Redi (known as “L’Aretino”), devotes his long poem about wine to how the stuff from different places has different character. He adores Chianti, and particularly the wines made by the ancestors of our author, Pietro Antinori, in ways that wines from other places don’t (he comes down quite hard on some of them).

Our author, Antinori, is not a writer of the class of Vergil or Redi. In both Italian and English, his book is readable, lively, and bit sporadic – it is probably not intended to read like a journal, yet that is what it most resembles.

But Antinori is, in his way, a creator of great classics. He invented the “SuperTuscan” wines: These are wines made with a great sense of what the French call “terroir,” a specific place characterized by local aspects. These wines were of a quality that stunned the wine industry when they first came out.

I am a “Roman” in my election of what part of Italy I belong to. I feel deeply emotional about the culture of the region of Lazio, and, to Commenditore Antinori, this makes me into a kind of subhuman creature . . . it’s a bit like New York and California . . . anyway, I would gladly give up the bottle of Cesanese del Piglio that I drink with my pajata (a dish made from the intestines of a very young calf while they are still filled with the milk of the mother) in exchange for a half a glass of a SuperTuscan. There is simply nothing like them.

In fact, Antinori has given a new meaning to the French idea of “terroir.” Originally, a Sancerre from the Loire had certain specifics that identified it as coming from that region, and that meant ‘terroir.’ Antinori, with his new wines, expanded the definition of “terroir.” These wines had a completely original approach, nothing necessarily to do with local tradition. And they were mind-bendingly delicious, with complexity of nose and taste that few other wines had. It was as if the wine had come to define the place, instead of the other way around.

The SuperTuscans redefined not just the Italian wine industry, but set standards for wine around the world—they made us all think about wine differently than we had before.

So Antinori’s book, while it is not poetry, falls into the same tradition as the poetry about wine above. All of Antinori’s thinking about wine is related to geography:

“In the late 1990s, my daughters and I began to look for land where we could grow grapes for high-quality sparkling wine…We found the ideal land in an enchanting corner of Lombardy, between the lake and the mountains. The vineyard is surrounded by a brolo, an old garden wall, near a small town with a smattering of medieval churches and a fifteenth-century villa. It was love at first sight . . .”

But the right land must be treated the right way:

“Locating the ideal plot of land is only the beginning. It takes three to four years just to begin production. Then it takes another five to six years for the vineyard to become more mature and capable of producing high-quality grapes. Then, especially when we’re talking about reds, it takes a minimum of three to four years of aging in the cellar. There are relatively new wines whose reactions to aging we can only guess, so there is a high risk of opening the bottles too soon or too late. There are also vineyards that have been around for ages and produce some renowned wines but are becoming their best selves only now, ten, twenty, even sixty years after they were first cultivated.”

The long-term vision is what Antinori tries to explain in the book. He tells the story of how his company had to separate from a beverages industry partner, because the latter was too worried about the quarterly bottom line. Very gradually and carefully, Antinori grew his company by making great wines, and by expanding to make more of them. The story is well told in the book.

More important, at least for this reader, is the way in which Antinori worked closely with his collaborators to create the great wines his company makes. If you care about wine, the story behind the creation of Tignanello or Solaia is well worth learning. There is also much about the long history of the family and building of the wine business.

But best of all, are the bits of poetry in the book that link Antinori’s winemaking to the vision of Vergil and the great tradition of wine and terroir:

“In 1350, nobleman Angelo Monaldesci della Vipera built a castle four hundred meters above sea level atop a clay-covered, tuffstone hillock not far from the border between Umbria and Tuscany . . . In 1940, my father bought twenty-five plots on the estate. The land he bought was in terrible condition. It would take fifteen years to set it right. By the early 1960s, those cellars were a model of innovation. Still, the castle, complete with medieval armor and frescos, would only fulfill its destiny as a producer of a great white wine a good time later.”

One gets a good sense from the book of the role of Antinori’s family—his three daughters now help him run the business. And though the business now extends across the globe, that sense of family roots in Tuscany, in a certain aesthetic, in specific values that link it to its birthplace, is perhaps the best thing that the book communicates.