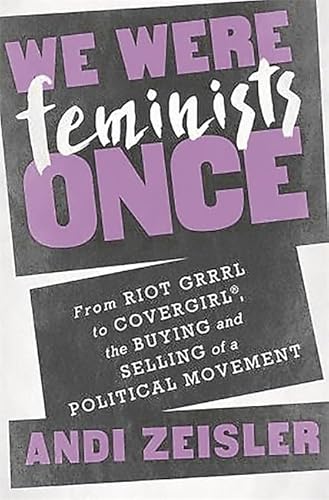

We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl®, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement

Andi Zeisler, cofounder and creative director of the non-profit organization Bitch Media, sets out her stall in her introduction, reminding us that the point of the magazine Bitch was “to take pop culture seriously as a force that shapes the lives of everyone, and argue for its importance as an arena for feminist activism and analysis.”

She poses the question as to whether the current visibility of “feminism” in pop culture—Beyoncé, Emma Watson, Taylor Swift are some recent flag-carriers—will result in “ trickle-down to true political equality” or whether pop culture’s embrace of feminism gives the illusion that the women’s rights movement is making advances when in fact the reverse is true.

Over 200 pages later after some rigorous analysis of the co-option of what she terms “market-place feminism” by advertisers and marketing, by celebrities, film, and television, she sensibly concludes “These days, I’m much less interested in who labels themselves feminist and more interested in what they’re doing with feminism. I no longer see mainstream acceptance of the term as the end goal, but as a useful tool for activism.”

Zeisler’s expectations for both pop culture and for feminism—both individually and collectively—may have been unrealistic. Pop culture is better at reflecting the zeitgeist, with perhaps some additional decorative touches, rather than actively promoting social change.

The essence of marketing, as she entertainingly demonstrates, is to search out the concerns of potential consumers—“empowerment,” “choice,” “slimness,” “fear of body odor”—and present a given consumer product as the answer to that concern. Most movies are directed and produced by men to reach the largest possible audience as entertainingly as possible—though there are some more enlightened “Indie” examples that she misses. And having women who are clearly already the “haves” (Angelina, Madonna, etc.) lending their lustre to the term “feminist” will not make a difference to women factory workers in Bangladesh or address the gender wage gap anywhere.

The most substantive chapter and one which probably deserves a book in its own right is Killer Waves, which addresses in passing the incoherence of the wave metaphor of feminism, and, more critical to Zeisler’s overall thesis, the way in which media have spun various aspects of the movement to the latter’s detriment.

Feminism has never been a popular movement—in either sense of the term popular—and its co-option by popular culture is not likely to change that situation one way or the other.

Feminism has long been a narrow church, a movement divisive internally and, as Zeisler rightly notes, usually excludes emerging constituencies, e.g. LGBTI, which share some of the same problems with “the patriarchy” and could therefore be strategic allies.

Few men are currently “invited” into the movement’s ranks, and it seems rather unlikely that Emma Watson’s HeForShe call to arms will expand the base! There is a problem with the basic product—feminism—that popular culture cannot and was never supposed to solve.

Zeisler has some extremely insightful things to say, but her argument would have been enriched if she had expanded her brief by taking more account of the political, economic, and social factors to which both feminism and popular culture respond.

One cannot, however, quarrel with her conclusion that the actual term feminism, once freighted with images of bra-burning, hairy-legged harridans has now become so lightweight as to be meaningless.