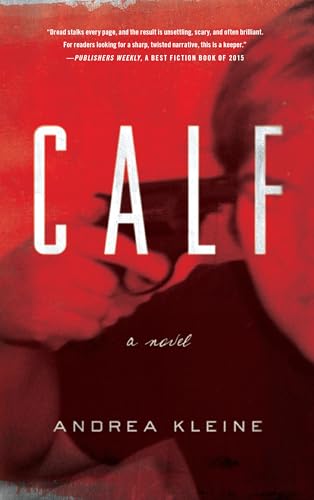

Calf: A Novel

Ronald Reagan was just 69 days into his presidency when John Hinckley, Jr., greeted him outside an AFL–CIO conference by firing six shots from a .22 caliber revolver. Taking cues from the film Taxi Driver and Lee Harvey Oswald, this was the 25-year-old’s desperate attempt to impress—or at least win—the attention of Jodie Foster.

It was an attempt surreal enough to suit the times. John Lennon had just been assassinated, a strange cancer was affecting the gay population, an actor had become president, and every kid knew what to do when the Russians attacked: cower under your desk while the world around you was sucked up in a mushroom cloud.

But things were bound to get even stranger: In the psych ward he was sent to, Hinckley would strike up a romance with a suburban socialite mother, Leslie deVeau, who had killed her daughter and lost her arm trying to take her own life right after.

Now, Andrea Kleine, New York–based performance artist and childhood friend of the daughter who was murdered, has claimed these two enigmatic events as source material for her debut novel Calf.

By and large, the novel alternates perspectives chapter by chapter, following a fifth-grader named Tammy and a Hinckley-inspired college dropout, Jeffrey Hack. Tammy’s narrative is narrow in scope, confined in large part to the microcosm of being a young girl in the early 1980s—stealing sips of wine, learning about sex toys, and showing off her stepfather’s gun between rehearsals for the school production of The Wizard of Oz.

And for the first half of the novel, Jeffrey’s story is just as narrow. He fights with his parents, moves to California to try his hand at songwriting, and heads back East before long, directionless and defeated.

If not for the blurb about Hinckley and deVeau in the novel’s front matter, readers might mistake the first half of this book for two coming of age stories—a cross-section (if not an especially incisive one) of what it was like to be as a young person in early 1980s suburbia. Readers looking for the promised spine-tingling page-turner will be tempted to put the book down before they get to the events that inspired the novel.

Those events, the murders we’re warned to wait for, do come eventually as promised, and each is as grisly and devastating as you might hope for. In Kleine’s rendering, the suburban filicide is stranger, and in many ways spookier, than fiction.

But readers looking for insight into the crimes—a telling glimpse into the mind of a young man who comes to believe he has a relationship with a Hollywood actress when he doesn’t, a man so enveloped in a parasocial obsession that he contrives a murder to bring him closer to his object of affection; or a glimpse into the mind of a young mother who believes angels are instructing her to off her daughter—may be disappointed.

Readers looking forward to the story of how two murderers meet and fall in love will be just as disheartened. This anticlimactic scene comes late, delivers little that the front-matter author’s note does not, and fails to connect in any satisfying way the two discrete narrative threads.

If Kleine had presented the story as nonfiction, readers might be more inclined to accept the perplexing murders as historical curiosities, fantastic episodes lacking the kind of backstory or motives we expect from fiction. In presenting this story as a novel; however, Kleine squandered the fiction writer’s unique opportunity to explore—or invent—the puzzling motives behind these violent episodes. Or, where motive lacks, she wasted an opportunity to unpack these murderers’ demons, to give her readers the biographies that lead to the acts that shocked the world.

It follows then that these characters never quite come to life. Tammy, the ten-year-old Kleine stand-in, comes the closest, though her sections are dominated by textbook domestic tiffs with her sister and stepfather. And even as we see Jeffrey’s mental state deteriorate, the evolution is never wholly believable, nor the stakes high enough . . . until the moment comes that we’ve been anticipating, one already softened by its predictability.