Woman on a Shaky Bridge

The title of Millicent Borges Accardi’s poetry chapbook, Woman on a Shaky Bridge, does not come from any of the lines of the 16 poems in this collection but rather from its preface, which describes a 1974 social science experiment conducted in Vancouver in which an attractive woman researcher spent time on two nearby bridges, one low and sturdy and the other high and shaky, chatting with passing men.

A roughly equal number of men on both bridges asked for the researcher’s phone number, but the majority of those who followed up by phoning and asking her out on a date were men she met on the high shaky bridge. The researcher concluded that the men mistook anxiety for attraction.

It occurs to this reviewer that the men who chose to cross the high shaky bridge were more fearless and adventurous than those who chose the low sturdy bridge, but that digression is not germane to the theme of misapprehended motivation in the poems that follow Accardi’s preface, poems which differ from the confessional voice prevalent in contemporary American poetry for the past half century by mostly describing other people’s lives and situations rather than the poet’s personal biography. By maintaining this critical distance Accardi becomes the researcher on the bridge; her poems achieve a refreshing objectivity, while their imagery heightens the dramatic power of her subject’s lives.

“Ciscenje Prostora (Ethnic Cleansing)” describes a rape that occurs in the Bosnian War:

“Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia; the countries undulate

together while he dances the dance of the basilisk

thighs marching, marching.

Even little sounds, like birds overhead,

encourage him to go on, to spit, to breathe

three generations of her surrender into his lungs.”

For her part the woman being raped tells herself that if she survives and outlives the enemy she wins. Accardi returns to the theme of humanity’s inhumanity in “Portait of a Girl, 1942,” “Only More So,” and “In Prague.” “Portait of a Girl, 1942” is based on a photograph taken of a girl a few hours before she was deported to a concentration camp. Four of the poem’s five stanzas begin with the phrase “I am the mirror for . . .”; the portrait of the girl represents the millions of victims whose faces remain unknown and the many millions more who stood by in silence. “Only More So” explores soldiers looting a private home and terrifying its occupants. “In Prague” describes the unexpected excavation of the skeletal remains of murder victims.

In “Coupling,” a poem comprising ten couplets and a solitary final line, a woman having an affair with a married man congratulates herself on how good she is at taking precautions that will keep her paramour’s wife from finding out and on her “talent for being aloof.” Accardi’s imagery makes effective and unexpected use of construction lumber: “. . . her heart compact as plywood.” And “. . . The bulk of her time/a two-by-four dovetailed into a corner,/getting the best he had to offer.”

The short lines of “A Raga for The Full Moon” mellifluously employ lyrical imagery to describe a piano bar. Accardi uses a similar approach less successfully in “For John, For Coltrane,” an unfortunately reductionistic portrayal of a multidimensional great musician and human being. She returns to a jazz theme more successfully in “Ascenseur pour l’enchafaud—Take II (The Lift to the Scaffold)” which describes American jazz musicians in Paris in 1957 recording the soundtrack to a French movie.

“This is What People Do” is a long list poem that itemizes the activities engaged in by chronically unemployed and retired Americans. “Buying Sleep” is a sweet poem that captures a tender moment between two brothers (one six and the other twelve) as recounted by the younger one. “Swinging Open” and “Sorting Through (found poem based on a note from Marc Marino)” recount family recollections.

“The Well” relates what two-year-old Jessica McClure must have experienced sitting at the bottom of a well for two days while the adults above ground worked to rescue her. “The Rattlesnake in Front of my House” describes a less famous emergency. The final poem of the collection, “Inventing the Present,” employs the imagery of an apple and apple tree to convey the senses of completion and loss of identity that coupling entail.

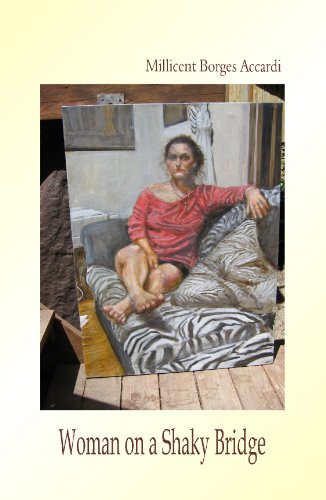

Woman on a Shaky Bridge is a handsomely presented, side-stapled chapbook tied with a ribbon. The striking cover photograph is of a wooden deck on which leans an oil or acrylic on canvas painting on of the poet painted by her father. In the painting the model sits on a zebra striped sofa with her hair tied back wearing black shorts and a red top with one shoulder exposed looking pensively at the viewer (or at the painter).

Woman on a Shaky Bridge would make a lovely gift for a poetry reader.