Sacred Monsters

“In the Spring of 2012 a new novel from Edmund White entitled Jack Holmes and His Friend, is upcoming. The reader hopes that with this new work of fiction Mr. White will restore the luster to his image as a literary master—a luster he has lost with the publication of Sacred Monsters.”

In a nifty bit of literary camouflage, author Edmund White offers us Sacred Monsters, a collection of purported “critical essays” on those literary luminaries—most especially those literary luminaries whose sexual appetites tended toward the bisexual and homosexual—whose level of achievement or fame has earned them the distinction of being dubbed a “sacred monster”—or perhaps better translated in present-day argot, “holy terror” better suits.

In explaining both the focus and scope of his text in his Preface, Mr. White comments:

“In French the expression monstre sacre is a familiar one and refers to a venerable or popular celebrity so well known that he or she is above criticism, a legend who despite eccentricities or faults cannot be measured by ordinary standards. A fixture on the cultural horizon. A ‘personality’ of exceptional renown whole fame is secure and never fluctuates. I can’t help but picture an enormous century-old goldfish swimming about in a murky pool on the palace grounds, though I think the correct image would be something like the Sphinx, half human (or animal) and half divine. In America Bob Hope in old age would have been a sacred monster; Lady Gaga is our newest one.”

With the definition of terms complete, White then sets his terms for dealing with these terrors:

“I fall into the category of those cultural critics who appreciate more than they evaluate their subjects, who admire more than they judge, who seek to untangle influences received and given, and hope to place a writer or painter into an artistic landscape and maybe even trace out the shape of a career. Having written three biographies of writers (Genet, Proust, and Rimbaud), I have more confidence than most critics do in the biographical approach. Biography, I suspect, is often the hidden agenda behind abstract critical evaluations presented as pure speculation or theory.”

Ah, but what, the reader asks, is the hidden agenda behind Sacred Monsters?

White then continues by noting that, of the myriad subjects considered here, some 15—a rather large majority—“were gay or bisexual or closeted or conflicted about their sexuality.”

Thus Sacred Monsters falls well within Mr. White’s own literary canon. As one of our modern day’s finest authors, most especially within the realm of what was once called “Gay Literature,” the authors he writes about here are among his own literary icons, idols and mentors (as well as a few bête noirs thrown in for good measure).

All of which should make for one of the more exciting new works of the new year. But there is an issue—the matter of that camouflage.

What is painted as a serious work exploring how the issue of sexuality—from the outsider stance of the gay and bisexual to the struggle of the closeted and the conflicted—is, in truth, a crazy quilt of odd bits and pieces, book reviews from the New York Times, and the New York Review of Books, essays from After Dark and the Times Literary Supplement—even, in the case of the volume’s lengthy piece on Robert Mapplethorpe, a reprint of an introduction for a 1995 publication of photographs named Altars.

Therefore, the reader soon realizes that instead of a consideration of our culture’s literary icons stressing how and why specific issues of sexuality impacted their lives and work, that which is contained within these “sacred” covers is nothing more than errata, pieces that, instead of speaking to a given writer’s body of work, speaks to a single book being reviewed, making the book’s narrative through-line, that whole consideration of one of today’s leading gay authors considering his forefathers (and mothers) in terms of both their sexuality and the impact that they had upon the culture of their day, tangential at best.

All of which may seem a mean cheat, but the book contains some wheat and well as a good deal of chaff. Of particular interest are the pieces that seem to awaken some passion in Mr. White. Among these is “Sweating Mirrors,” an interview that Mr. White did with perhaps the most monstrous of the sacred, Truman Capote, who hosts our author at home on the hottest afternoon of the summer:

“I was looking forward to the frigid embrace of Truman Capote’s apartment in the United Nations Plaza, but when I stepped off the elevator he was standing barefoot in the hallway with a torn pink palmetto fan in hand and a drenched white T-shirt, and he told me that his air conditioner was on the blink. He was thin-lipped and cheerless and so faint that his voice was nearly inaudible as he led me into a small sun room that looked out on the steaming East River and the UN Secretariat, which today looked up more like a static tornado than a building. The huge windows of the sunroom were sealed shut, and the only air came from tiny vents ajar below them.

“We sat at opposite ends of a large Victorian couch (‘My grandmother’s,’ he said) and looked at the larger adjoining sitting room and its mirrored wall; even the mirror was fogged and perspiring.”

This setting of the stage and the agonizingly difficult interview that follows (“He stood, paced around. His hand was trembling. He excused himself and left the room. When he re-emerged in a few minutes he seemed calmer . . .”), as well as Mr. White’s lengthy consideration of Capote and his work makes this perhaps the most satisfying piece in the book.

Also of interest is “The Strange Loves of John Cheever,” as this reader is always interested in tales of Cheever and his bleak literary landscape:

“Stendhal once said that writing should not be a full-time job, and John Cheever’s unhappy life seems to lend substance to his remark. He had too much free time, too much creative energy, too many hours to feel lonely or to drink or to get up to sexual mischief that he immediately regretted. He was both a reckless hedonist and a starchy puritan, just as he was also a freelancer with pretensions to being a country squire, both unfortunate combinations. Oh—and have I mentioned that he was bisexual? And a self-hating little guy who was always ripping his clothes off at parties and plunging into the pool, then mourning his exhibitionism and small penis in his journals the next morning?”

Does it get any better, this image of Cheever (big brain, small penis), “mourning his exhibitionism” the morning after?

With sections like these, White sets a bar for what we, the readers, feel we deserve in such a work. But it is largely downhill from here.

Take for instance, “A Love Tormented But Triumphant,” Mr. White’s melodramatically titled review of the exquisite second volume of Christopher Isherwood’s personal journals, entitled The Sixties. While Mr. White happily gives Isherwood is full due, most especially when he refers to Isherwood’s novel A Single Man as “the most openly gay novel and the founding text of modern gay literature” and embraces and respects Isherwood’s deep study of the Hindu religion far more than modern Western critics tend to, things become a bit more prickly (to use one White’s own words for it) when White considers Isherwood’s relationship with his life mate, painter Don Bachardy. Of this relationship, Mr. White writes:

“They had become lovers in 1953, so they have already been together for seven years when this volume begins. Don had been just a typical Hollywood kid when they first met—in love with movie stars and beach and dancing. But in his years with Isherwood, Bachardy acquired an English stutter, a great ambition to be an artist—and a very prickly disposition.”

Worse, Mr. White crosses a line in this piece that he tends to cross again and again in this volume and inserts himself into his book review when he comments, “It’s a miracle they stayed together until Isherwood’s death, in 1986. I knew them as a couple in the early ’80s, and by that point they seems completely harmonious.”

And yet, harmonious as they seemed, author White saw fit to pass judgment on their enduring relationship, not on the basis of the work he was supposedly reviewing—In the name of full disclosure, I should state that I reviewed the same volume for the New York Journal of Books—but on the basis of his own perceptions.

Which exemplifies perhaps the greatest flaw with Sacred Monsters. The fact that Edmund White is himself a Sacred Monster of sorts, a writer whose lifeline traces the timeline of gay literature.

The impact that Mr. White has had on literature at once allows his viewpoint an extra cup or two of gravitas, but, at the same time, his “I remember it well” intrusions into his own works of literary criticism to take on the tenor of talk show host Dick Cavett’s rather endless anecdotes involving evenings spent with Groucho Marx and Woody Allen and New York taxis and late night dinners at Elaine’s.

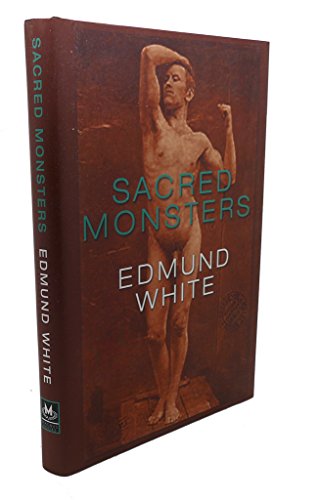

Indeed, in his very first essay, White steps away from the topic of his book and, instead of getting on with a consideration of the work of Edith Wharton (who has to wait for the second essay), turns his attention instead to a statue of Rodin’s called “The Age of Bronze.” Why? Because Rodin was closeted and confused? Wantonly Gay? No, because, as Mr. White puts it:

“When I was fifteen I fell in love with this statue—not as an art fancier or potential collector or historian, but the way a lover would. Literally. I was a lonely gay kid living in the dorms at al all boys’ school where I would have been beat up if anyone had guessed my inclinations.”

With this, very likely, a sacred monstrosity is born.

This sense of being a sun around which other orbs revolve (perhaps the best way to quickly identify and define a sacred monster, along with the necessary excellence of their body of work), along with the sense that the pieces included here were gathered from the bottom of desk drawers, the backs of packets of matches and crumpled paper napkins together combine to make Sacred Monsters something less than sacred and something more than monstrous. It is a disappointment of the first order.

In the Spring of 2012 a new novel from Edmund White entitled Jack Holmes and His Friend, is upcoming. The reader hopes that with this new work of fiction Mr. White will restore the luster to his image as a literary master—a luster he has lost with the publication of Sacred Monsters.