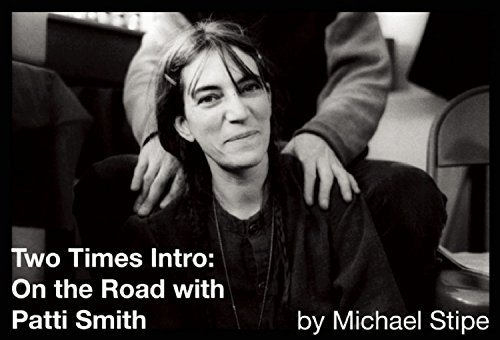

Two Times Intro: On the Road with Patti Smith

“. . . examined holistically, Two Times Intro: On the Road with Patti Smith is an energetic and gracious tribute to not only a great artist, but also to a powerful moment in her oeuvre—and to those who contributed to it and shared in it. It’s telling that such an experience of light and warmth can be extracted from images of mostly stark, disorienting, and nominally lifeless nighttime interiors. Perhaps the night really does belong to lovers.”

Once upon a time, two musical poets joined amps to undertake a journey of life and love, war and peace, sound and stillness. When Bob Dylan and Patti Smith rambled their way across the USA in the mid-1990s, it was an opportunity to double the inspiration that could be drawn from just one of these modern bards. Amid the sounds, the words, the layers, and backbeats, another poet was entrusted with the vision to capture the experience in photos: REM’s Michael Stipe. The result is Two Times Intro.

In 1995, Patti Smith had been coaxed to return to live performance after many years on hiatus. The singer and songwriter had dropped out of the public eye to, as biographers might say, to “find herself again,” which for a perennial soul-searcher like Smith might actually be her daily routine.

The absence of the voice and guitar behind some of the mightiest pre-punk challenges to perceived notions of contemporary adult music had, by this time, become a weighty dark star in the galaxy of modern commercial music—which, by the mid-1990s, was smothered in grunge culture, marked by Smithian chord distortions, and nihilistic, anti-fame postures. Her return was enveloped lovingly by an adoring fan-base and newly spurred acolytes.

Like slices of skin peeling off from the musical adventure this journey symbolizes, Mr. Stipe’s pictures record the erratic, hurried, half-sensed behind-the-scenes movements of the players and entourage and, the star herself (though perhaps oddly no shots of Mr. Dylan).

Ms. Smith, the subject even in the shots in which she doesn’t physically appear, offers a fine portrait. In parts boyish, pensive, disheveled, goofy, and disarmingly warm, Ms. Smith’s various angles offer views on a life well lived, carrying its joy and pain like a warrior’s shield. Both scary and beautiful, she is quintessentially feminine.

She offers an intriguing paradox: lank, corded hair falling gently over her guitar as her soft womanly hand strums a melody or the storm trooper boots paired with a face carrying a sky-burst smile; Ms. Smith bears all the iconic heft one would expect from one who has authored some of the rock age’s more salient moments.

Yet the pictures where Ms. Smith is absent, or only slightly visible, are the ones in which her sincerity and honesty are more clearly felt. Two standout snaps attest to her charismatic force. The first, of her limp smock hanging before or after a show on a coat hanger against a blank wall, looks ancient and rustic. Stained, faded, and unironed it is like a museum piece, a relic of a soul long gone, standing in ironic counterpoint to its wearer, who may have been considered such prior to the tour this book tracks. A passerby (possibly Mr. Stipe himself) only emphasizes the mute power of the garment’s filler.

A second, of Ms. Smith’s bent arm etched against a strobe lit interior of a gig—a light-orbed drum kit hovering in mid-distance—seems to capture the performer’s stated desire to “disintegrate into light.” The diaphanous cheese-cloth fabric of the sleeve, the crooked arm, the light, the glimpse of ratty hair—all have a scarecrow quality, a sense of something that looks like a body where the soul has somehow transcended and hovers untethered. Fingers reach like that of a skeletal zombie, clutching at the light and warmth of the performance, the artery of its owner’s art.

Ms. Smith’s fellow actors lurch, slouch, and shuffle across the pages as largely anonymous spirits. In this sense, captions may have added to the narrative force of the photo-essay, peopling it with figures those of us not in the-know might relate to or have heard of, or even seen.

The textual tributes to Ms. Smith dotted throughout add little of real value as they come across as over-gushy if “edgy” genuflections to the lauded Ms. Smith, who might herself, presumably, scowl at these occasionally sycophantic Arabesques.

The characters of some of those who have apparently penned these somewhat arch exercises stand alone as interesting, generous and sincere folk who might have been best left to trace themselves in patterns of light and shade on photo paper rather than be given a notebook. The admiration and appreciation of their place, the sense of love and spirit that moves through many of the images speaks volumes for the relationships that held this moment in rock history together.

Most look like they should be out hugging trees, not stuck in the claustrophobic confines of dressings-rooms, hotels, and backstages. They are like lost souls, forever wandering around a disused hotel. Trapped hence under layers of urban grime, it seems most can’t help but to shine their light into the dark crevices of America’s Gothic interiors.

That Mr. Stipe and his co-credited photographic collaborator Oliver Ray have managed to present the unseen light amid the film noir grays and blacks of a rock-and-roll tour, drawing the warmth emanating from the cold indoor spaces, attests to good eyes and to the presence of a curator’s skill to allow the sum to tell the stories of the parts.

While some of the selected images sit on and occasionally topple off the razor’s edge between bona fide statement and creative indulgence, examined holistically, Two Times Intro: On the Road with Patti Smith is an energetic and gracious tribute to not only a great artist, but also to a powerful moment in her oeuvre—and to those who contributed to it and shared in it.

It’s telling that such an experience of light and warmth can be extracted from images of mostly stark, disorienting, and nominally lifeless nighttime interiors. Perhaps the night really does belong to lovers.