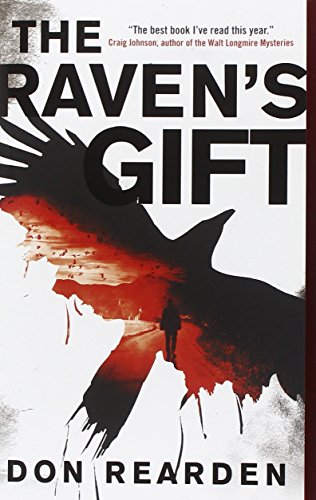

The Raven's Gift

The Raven’s Gift is Don Rearden’s debut novel. In it he shares stories he learned from elder residents as he grew up on the tundra of Southwestern Alaska.

He offers The Raven’s Gift as a cautionary tale based on his contention that this knowledge is critical to the survival of tradition and to our own personal survival as well.

The author witnessed the consequences of “soul-consuming ways of living” that rejected traditions that had previously sustained people for thousands of years.

As a young student, he remembers that Alaskan history emphasized the struggle for statehood, but there was no mention of the destruction and disease brought by outsiders in the late 1800s. It was only after reading The Eskimo About Bering Strait by Edward Nelson that he really understood the ghastly extent of the epidemic of 1881.

This information provides a backdrop for The Raven's Gift, actually three intertwining yet separate layers, set in a more contemporary timeframe.

The first is of a young couple, the Morgans, from the lower 48 who are eagerly anticipating their adventure as new teachers in a Yup’ik Eskimo village on the Alaskan tundra. A passenger on their plane seizes the opportunity to welcome them, but also warns of botulism from a fish head delicacy that is enjoyed by Alaskans. (Don’t eat it—ever).

The couple is advised to stockpile canned goods as a hedge against lean times—especially if the salmon do not return. They take heed, not realizing the prophetic nature of these caveats.

As a teacher, dialogues get heated as John Morgan prods his students to think beyond the obvious and shake off their cultural torpor. These vignettes and many more set the stage for what is to come.

We find ourselves quickly immersed in the second of these stories as John plans his escape after an epidemic has taken all but a handful of survivors. He faces unbearable grief in addition to starvation and sets off to find help—always looking over his shoulder.

Not far into his journey, he encounters a young Eskimo girl. “Blind. Starving. Dehydrated. She was already long past dead.”

This presents the dilemma of deserting her versus taking on the increased burden she represents. But something compels him to put down his hand gun and carry her along. An elderly woman soon joins them and her wisdom contributes to their survival. She counsels John about the young girl: “Trust her eyes. She sees more than (we) ever will.” And she does so—time and again. Together, they slog their way toward survival through the freezing tundra.

Deftly woven in, like the grasses which the young girl is constantly braiding, is an allegorical third layer of “story telling.” Their survival hinges on this knowledge and educates the reader to ancient lore.

The elderly woman cautions against taking provisions from the school where hundreds of bodies are stored like cord wood. Despite the near starvation of this trio, the woman argues that taking food from the site is like robbing a grave and could have dire consequences. It also explains why no one else has attempted to do so.

In another situation, the Eskimo girl (whose name, Rayna, we only learn much later) senses the presence of a raven. She shares the Yu’pik tale of the raven, which brings luck—thus the title of this book.

The girl’s incessant chatter is peppered with inquiries about her cousins. “Where are they? What happened to them?” When they encounter stacks of bodies in the nearby school, none are children. One is left to ponder the fate of these little ones. At first, this might be lost on the reader, but think: Is the author trying to tell us something? The answer comes later.

The tension is further complicated by the ominous presence of a hunter who shadows them. Who is this person? Why are they afraid? Ultimately, we learn of his identity and mission.

If there is any flaw to the writing, it is that the author relies too heavily on flashbacks. The reader is jolted back and forth between competing subplots. This produces backtracking, rereading, and confusion. The story would have been enhanced by a more linear storyline and a less ambitious plot.

Yet the author has achieved a very important goal. He has shared Yup’ik oral tradition and taken us deep inside a contemporary fictional tale based on a horrible period in Alaska’s history.

Once learned, tradition cannot be taken away. “They (the stories) exist so that we may continue to exist.”