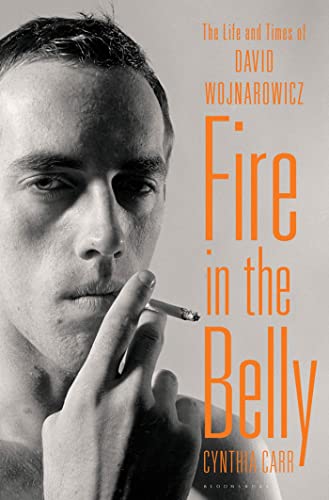

Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz

“Fire in the Belly is a book comprised of many dark days. . . . a traffic accident of a thing. Fascinating . . .”

Perhaps the most powerful moment in the extraordinary new biography of artist David Wojnarowicz ironically occurs minus the book’s central figure.

In it, as in much of the rest of the book, the ‘80s are not so much recalled as recreated in the mind of the reader. And in this moment in the text the reader experiences the beginning of the culture wars, something that would soon come to include Wojnarowicz himself:

“Robert Mapplethorpe’s beleaguered retrospective ‘The Perfect Moment’ opened in Cincinnati on April 7. I was there to cover it and will never forget the moment when the police came bursting into the Contemporary Art Center, pushing away the artgoers and knocking down velvet ropes as if chasing some deadly criminal.

“The police cleared the museum, which was on the second floor of a downtown mall and had been full to capacity. Between those thrown out and those who’d been waiting to enter, many hundreds of people soon stood on the mall’s ground floor. Museum director Dennis Barrie came out to address the, covering his face with his hands and telling them, ‘It’s a very dark day.’”

Fire in the Belly is a book comprised of many dark days.

It is a traffic accident of a thing. Fascinating, especially for the ghoulish among us, and bitingly horrific in a “there but for the grace of God” kind of way.

It is a book that will be read both compulsively and convulsively.

The reader will find himself tearing through its nearly 600 pages in fits and starts, staying up way past a time when sleep would ordinarily come. It is the worst possible type of bedtime story, one that is honest and unblinking. That traffic accident conundrum: not wanting to see but unable to look away.

Early on, midway through the recitative of a childhood that author Cynthia Carr so rightly calls “Dickensenian” (with abuse, neglect, betrayal, abandonment, and life of the streets bankrolled by hustling all featured in what may be called Wojnarowicz’s “formative years”) the reader begins to grasp not only about the details of the artist’s life, but also how these experiences informed his later artwork.

And this is the particular gift that the book has to offer, the thing that raises it far above what we have come to see as the “typical” biography of the famous and/or accomplished: insight.

That Cynthia Carr has written for Artforum and the New York Times, among many other publications, lends authority to her author’s voice. That she used the byline “C. Carr” for her many articles for the Village Voice during the art explosion of the 1980s enhances her credibility.

And that she herself knew David Wojnarowicz, most especially in his final days (the story of his gift to her of a prized camera once owned by Peter Hujar is especially moving) lends her work a special sensibility and sensitivity that a more objective, less heartfelt work would lack.

Thus there is a sharp, even jagged edge to the work as Ms. Carr recreates a culture that bloomed seemingly overnight in the rubble of 1970s New York, only to disappear all too soon as AIDS devastated the community and destroyed a generation of young artists in less than a single decade.

But then how could it be otherwise and still tell the story both of Wojnarowicz—who would achieve fame through the raw and striking imagery of his collages and infamy through his video work “Fire in the Belly” and through his still images, most notoriously that of fire ants crawling over a crucifix—and of the culture in which he thrived?

Fire in the Belly is, after all, a tale emblematic of its time and place, of an artist and his art.

Of a boy who survived on the streets, who, after barely finishing high school and never receiving anything in the way of art training, managed to channel his considerable rage into writing (his own collection of essays Close to the Knives is an extraordinary work for those wishing to learn more) and art.

Of a gay man who, amazed and confounded by the fact that years after AIDS began its destruction of an entire generation, the President of the United States still refused to say the word, who again channeled his rage into political action, both as an artist and as a member of Act Up.

The world created here (Act Up founder, writer, and firebrand Larry Kramer is quoted as asking two thirds of a large audience gathered to hear him speak to stand up and then telling them that, within five years, all those standing will be dead.) is one that those of us who are old enough to remember might feel easier and better left unremembered, but one that must be examined and understood if we are to understand ourselves (and our politics) today.

And it is as if the work Wojnarowicz left behind is something of a Rosetta Stone by which we may translate the language of times lost. In understanding him, in scrutinizing his work and grasping the meaning of his “pre-invented world,” we come to understand ourselves:

“Though he hadn’t articulated it in 1986, he [Wojnarowciz] had found the subject matter that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life. Broadly speaking, this was what he called ‘the wall of illusion surrounding society and its structures’—false history, false spirituality government control. His shorthand for it was ‘the pre-invented world.’ He explained that phrase in Close to the Knives:

“’The world of the stoplight, the no-smoking signs, the rental world, the split-rail fencing shielding hundreds of miles of barren wilderness from the human step. A place where by virtue of having been born centuries late one is denied access to earth and space, choice or movement. The brought-up world; the owned world. The world of coded sounds: the world of language, the world of lies. The packaged world; the world of speed in metallic motion. The Other World where I’ve always felt like an alien.’”

Fire in the Belly is an uncompromising work that stands as a tribute to the brilliant, intensely difficult, and infinitely fascinating David Wojnarowicz.

But also it stands as a tribute to the whole of the time and the place and to the artists and activists, the gallery owners, the waifs, the street people, the junkies, the drag queens, and the yuppies in their ever-growing numbers who populated it.

Walking the streets are Lydia Lunch, Ethyl Eichelberger, Keith Haring, Cookie Mueller, Bill Rice, and Iolo Carew just as they should be. Also recalled are the “How’m I doin’” administration of Mayor Ed Koch, the riot in Tomkin’s Square, and Act Up’s “Die-In” all set in Ms. Carr’s jewel toned language.

And at the center of it all, as he should be (Keith Haring not withstanding), stands the six-foot-four-inch lanky form of David Wojnarowicz whose life, work, and death emerge emblematic of not just his generation, but of our own life experience.

As is this—written after his diagnosis of full-blown AIDS but before the ravages of the disease truly began—a consideration of death so wonderfully wrought that it rises up from the individual to become the universal:

“Will my death be terrible and difficult? Will I let go easily as a body among the waves or the reeds of a pond? Will I sink below the surface of life like a swimmer whose feet become entangled in the undulating weeds? Will I be embraced by all those who have gone before me? Will I be loved before I go? Will I turn to stone like a grey dot in a field? Will I burrow into the dream of the earth, the humming of the motor works? Will I speak in numbers or symbols? Will I shock myself by dying when I feel it is time, not waiting a moment longer than necessary?”

Once read, Fire in the Belly clings to the tongue, the eyes, the mind. It is a hard work to shake, a vitally important work to read, explore, and experience.