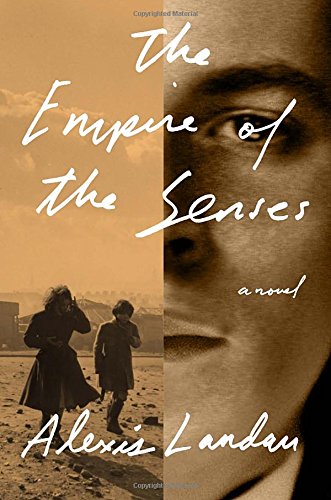

The Empire of the Senses

“For those who like history and drama, there is plenty of both in this novel, with good plot twists and turns.”

“My first wish is to see this plague of mankind, war, banished from the earth,” said George Washington—a sentiment readers might agree with after reading The Empire of the Senses, a first novel by Alexis Landau.

Set against the backdrop of World War I, Landau offers a sweeping saga based around the character of Lev Perlmutter, an assimilated German Jew who enlists to fight for Germany on the eastern front in 1914. Lev is married to Josephine, a gentile whose family disapproves of Judaism. Their strained marriage becomes a metaphor for the strained relationship between “Jewishness” and “Germanness,” in Berlin as anti-Semitism takes hold in the run-up to both WWI and WWII.

Lev goes off to war in a desperate search for his own identity. “This is what Lev wanted and what he believed Josephine wanted: to escape the faint doubt, the shadowy presence of another past, another history, he kept trying to outrun.”

Landau is painstaking in her detail about the frontlines of war. “The taller men always got shot through the jaw, the shorter ones through the eyes.”

Lev finds himself in an isolated town near the Russian border where he meets Leah, a Jewish woman, who becomes the love of his life. Their relationship becomes the window through which Landau explores Jewish ritual and life. Back home, Lev’s children, Vicki and Franz, struggle with their own identities and take diverging paths with the daughter embracing Judaism and the son joining the Nazi brown shirts. As with sagas, roads intersect and characters find their way home. In escaping the war, Lev leaps off a transport train and crawls home to Berlin, with the reader crawling along with him through his every thought and emotion.

At nearly 500 pages, The Empire of the Senses demands commitment and patience. Like war, it drags on a bit too long, tempting the reader at various points to bypass what can feel like repetitive dialogue. In short, no part of Lev’s life goes unexamined. “Lev observed himself in the cloudy mirror. What would Leah think if she saw me now? Had these nine years taken much of a toll?”

Alexis Landau takes the reader on a long journey through Germany, Prussia, the former Soviet Union, and America. For those who like history and drama, there is plenty of both in this novel, with good plot twists and turns.

By the end you will be exhausted and confused about the nature of war—and the nature of mankind and the degree to which maybe George Washington was right in suggesting that at least one of those be banished.