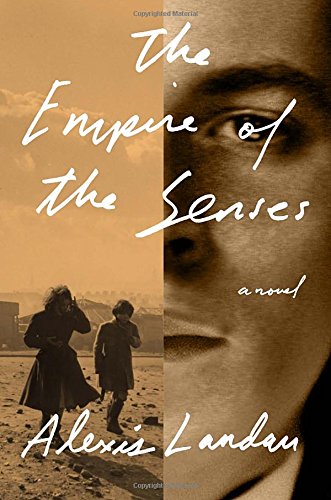

The Empire of the Senses

“[a] powerful and compelling novel.”

One of the ironies of German history in the first third of the previous century is that Jewish Germans were assimilating and intermarrying at such a rapid rate that had Hitler never achieved power, Germany’s Jewish community would have eventually disappeared on its own. Alexis Landau’s cinematically descriptive, character-driven debut novel explores ethnic identity via an intermarried family in WWI and Weimar era Germany, i.e. before anti-Semitism became official state policy legally codifying ethnic definitions.

In an article on the Jewish Book Council’s website Landau writes that she wanted to write about what it meant to be Jewish in an era before the Holocaust and Israel became important components of Jewish identity, yet her story of an intermarried family is also quite timely for 21st century America where one in two Jewish college students has a non-Jewish parent.

In contrast to the first two thirds of the 20th century when Jews marrying out were likely hoping to escape or transcend what they perceived as a disadvantageous Jewish identity, in America today Jews are widely admired, and many intermarried Jews have strong Jewish identities and are raising their children as Jews.

The novel opens in 1914 when at the outbreak of WWI 30-year-old Lev Pearlmutter enlists in the German army to prove to his Christian wife Josephine and her aristocratic family that he, a Jew, is as brave and patriotic as any gentile, even though it will take him away from their children, six-year-old Franz and four-year-old Vicki. Lev and Josephine’s courtship is described in flashback as the attraction of opposites, but by the time of his enlistment the marriage is already strained.

Part One, the first third of the novel, depicts Lev’s army service doing administrative work in Mitau, Latvia, well in the rear of the front, where he reconnects with his Jewish identity by falling in love and conducting a passionate affair with Leah, a beautiful and sensual illiterate war widow and rabbi’s daughter who is the polar opposite of the sexually repressed and unresponsive though educated and cultured Josephine, to whom Lev returns at war’s end out of a sense of duty to his children. Landau convincingly depicts sexual attraction, desire, passion and infatuation, but there are few if any portrayals of fulfilling mature marital love.

Part Two’s first six chapters take place on a single day in June 1927, and four later chapters occur on a single day in 1928, providing Rashamon effects depicting the same events from multiple perspectives. The Pearlmutters' marriage is even more strained and like their parents, the children, now university students, are moving in opposite directions.

A shorter novel by a less capable writer might dig no deeper than the family’s schematic surface rift: the blond haired nonintellectual, culturally conventional, and sexually repressed Josephine and Franz vs. the open minded, intellectually curious, culturally adventurous brunettes Lev and Vicki.

But all four characters are far more complex: during psychoanalysis with a gentile Jungian therapist whose treatment includes carrying on a torrid affair with her and sending her to séances, Josephine recalls being sexually abused as an adolescent by a family friend; Franz is a closeted gay man who is drawn to an all male nudist paramilitary camp that is a feeding organization to the Nazi brownshirts where he must hide his sexual orientation and use his mother’s maiden name; Vicki is a studious French major, ballet dancer, and a flapper who loves jazz, nightclubs, and her Jewish father and paternal grandmother; and Lev, an only child of estranged assimilating parents, his late father a businessman and his mother a Communist, who moved with them to Berlin at age two to escape pogroms in their native Galicia and who now misses Leah who was his one true love.

The plot becomes suspenseful when Leah’s nephew Geza, bearing a letter from Leah to Lev, arrives in Berlin to work, save money, prepare to move to Palestine, and he and Vicki fall in love. Will Lev travel to New York, Leah’s new home, to reconnect with her? Will Josephine leave Lev to marry her analyst? Will Franz the Nazi stormtrooper resort to violence to prevent Geza and Vicki from making aliyah and marrying? To find out readers will have to read the book.

Key dramatic moments include when Franz tells Josephine he wants to join a club that doesn’t accept Jewish members to which she replies, “We’re Aryan, Franz.” Another is when on their way back from a vacation in the Alps Lev, Josephine and Vicki pass through pro-Nazi Nuremburg where a young woman’s head is being shaved for associating with a Jewish man.

Discussing that event back home in Berlin Lev and Vicki remark “how grotesque, how inhumane that rally in Nuremburg had been.” But Franz and Josephine conclude “there must have been more to the story, that a young woman doesn’t just end up in such a situation without a reason for it.” After which Franz praises the Nazis whom Lev dismisses as a fringe group.

Vicki stops attending church with her mother and starts learning Hebrew and adopting Jewish practices with Geza and his friends. Vicki and Geza plan to make aliyah and marry, in that order, but there is no mention of Vicki—whose Jewish parent is of the wrong gender to make her Jewish according to Jewish law—planning to convert to Judaism so their children will be Jewish.

In the 1970s Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism adopted gender neutral bilateral descent to determine Jewishness, and in the 21st century children of gentile mothers and Jewish fathers such as Michael Douglas and Gwyneth Paltrow are raising their children as Jews, but none of that was the case in the 1920s. Maybe readers should infer or imagine Vicki converting, or perhaps this is one of a few anachronisms that must be overlooked to appreciate this powerful and compelling novel.

Other anachronisms include civilian radio stations during WWI and a return address on a 1925 letter from Latvia that refers to that then independent country as a “Soviet People's Republic” 15 years before its annexation by the USSR. Few readers will even notice such errors and those willing to overlook them will be rewarded by this handsomely written and otherwise extensively researched novel that conveys its complex characters' conflicted senses of identity and detailed accurate descriptions of Weimar era Berlin.

With that caveat The Empire of the Senses is recommended to readers of literary historical fiction.