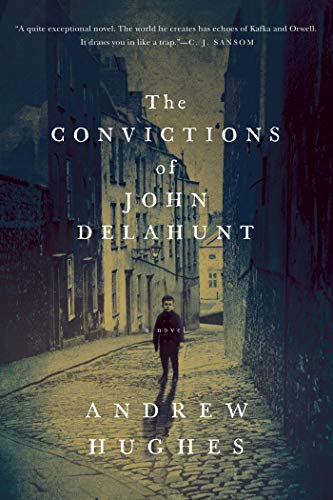

The Convictions of John Delahunt

Dublin: 1841. John Delahunt is a man of many faces: student at Trinity University, husband to Helen Stokes, police spy for the Castle, and condemned to hang for murder both as a fictional character and a historical figure. Based upon a historical murder case, The Convictions of John Delahunt by Andrew Hughes is a story both compelling and revulsive. One is compelled to continue reading even though Delahunt is both an unreliable narrator and a man lacking in moral character.

While locked in his cell awaiting execution, Delahunt writes his account of the events in his life leading up to his conviction for murdering the child, Thomas McGuire. “For me, there’s no need to dwell on the nature of providence, or trace back through decisions that led me here like a genealogist compiling pedigree. It’s clear where all this started.”

Delahunt tells of his first encounter with Thomas Sibthorpe, a man of authority at the Castle, headquarters for Dublin’s police and civil administrators. It is not clear what Sibthorpe’s title may be, or his exact position in the chain of command, but he is not a man to be crossed. “You will be required to make a statement to me regarding the events of Tuesday night, and the extent to which you assist our efforts is entirely up to you. I would consider that point carefully.”

Not much thought is required. Delahunt provides the false testimony Sibthorpe wants against a student accused of assaulting a police officer during a scuffle which Delahunt witnessed. His false testimony clears his friend, Arthur Stokes, who actually attacked the officer, but Delahunt didn’t lie to protect his friend. He did it because otherwise he would spend “A night in a dank cell; interrogated and physically cajoled into saying what I was at liberty to say already.”

Delahunt suffers no remorse for his part in sending an innocent man to prison, but instead relishes “the power it gave me over Arthur Stokes.” Stokes apparently believes that Delahunt saved him from prison, or so the convicted murderer records in his written account. Stokes also describes Delahunt’s involvement to his sister, Helen, “. . . who subsequently looked upon me with great favour.”

Delahunt’s next action as a paid informant was to interview a victim of an assault and obtain information on the identity of the perpetrators, which he turned over to Sibthorpe, not out of a citizen’s duty but for money. He is incensed to learn from Sibthorpe’s assistant, Devereaux, that had Delahunt waited two days to pass along his information, his pay would have increased by thirty pounds. The victim has died, turning an assault into murder. Murder, Devereaux tells him, “That’s where the money is.”

If it is more lucrative to inform on a murderer, then Delahunt will do so, even if it is necessary to provide the corpse himself, and point the finger at some convenient bystander. He has expenses, after all: his wife, Arthur’s sister, Helen, and such necessities as food, rent, clothes, and his fees for attending Trinity. Unfortunately, Helen’s family has disinherited her because of the marriage, and his own inheritance from his father went to pay the old man’s debts. “In essence, my house belonged to the bank.”

Delahunt records these facts of his daily life not as excuses for his crimes, although of course they are, but as circumstances that happened to exist at the time. He describes his murder of the Italian boy and his subsequent accusation of an innocent man. Not that Sibthorpe cares about guilt or innocence. He is interested in a conviction and headlines praising the police.

Delahunt’s life continues its downward spiral, exacerbated by his murder of the Italian boy. Helen becomes addicted to laudanum after an abortion, and Delahunt can’t help her, despite his efforts. Arthur Stokes takes his sister back to their family and forbids Delahunt from seeing her. The family demands the marriage be annulled and offer a small fortune as a bribe.

His marriage broken beyond repair and his finances nonexistent, Delahunt turns to the only occupation at which he has ever excelled; murder and false testimony.

Although such an immoral and vile narrator and a story that seems to leave no doubt as to its conclusion would usually not attract many readers, Hughes very skillfully begins to hint at Delahunt’s redemption. The evil of a bureaucracy providing incentives to not only lie, but to commit murder, provides another compelling reason to finish the book. Fans of thrillers want see evil punished, and fans of mysteries want their questions answered, most particularly, why did a character do what he did?

The Convictions of John Delahunt reads like a true crime book, and in many ways it is. Mr. Hughes describes the vibrant, but often cruel life, both social and political, of 1840s Dublin, providing a background that is essential to any true crime story. The murders of the Italian Boy and of Thomas McGuire were both real cases in Dublin, and generated sensational headlines at the time. Many of the characters in the novel are historical figures, and others are so realistic that they could be. John Delahunt himself was hanged for the murder of Thomas McGuire on February 5, 1842.

The Convictions of John Delahunt is best compared to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Both use real murders and real people, but Hughes fictionalizes John Delahunt’s “background, character, and family.” Capote’s information about his murderers comes from multiple interviews and a study of their records, but both books provide the same sense of immediacy and the suspicion that the characters are equally unreliable as narrators.